![]()

CHAPTER ONE

It’s Whose Thing?

The Isley Brothers and Rhythm and Blues

In 1991, reporter Isabel Wilkerson filed a front-page tale of two proms. The planning committee at Chicago’s Brother Rice High School had hired the kind of band that many black students detested. “They want that hard-rocking, bang-your-head-against-the-wall kind of stuff,” one senior complained, but he and other African Americans, only 12 percent of the school, were outvoted. A rival prom was soon organized. “And so,” Wilkerson wrote, “while about 200 white couples and six black couples danced to rock music in two adjoining ballrooms at the Marriott Hotel, about 30 black couples listened to [records by] the Isley Brothers and Roy Ayers, danced the Electric Slide and crowned their own prom king and queen.” Integration, Wilkerson concluded, had failed. An inability to even celebrate a prom in one place was more than a symbolic conflict. It reflected fundamental, unresolved differences over how to fashion a nation that could be collectively American.1

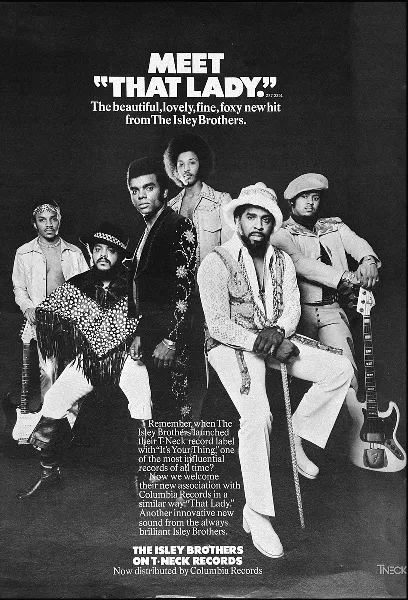

Too bad no one asked the Isley Brothers for an opinion. Their first hit, 1959’s “Shout,” epitomized what would become soul music, the sound of black liberation, yet it was revived in the blockbuster 1978 comedy Animal House as the ultimate white fraternity anthem. Their second hit, “Twist and Shout,” cowritten and produced by Bert Berns, the Jewish son of Russian immigrants, featured a Mexican version of an Afro-Cuban dance rhythm and would be covered and virtually trademarked by England’s Beatles. Guitarist Jimi Hendrix, one of rock’s few black legends after the late sixties, toured and made his initial recording with the Isleys. Their early seventies albums often contained cover versions of rock material, and their concerts in the later seventies were modeled on rock spectacle, with flash pots and guitar solos galore.2

Despite this crossover history, the Isley Brothers did not remain favorites of the white rock audience. If anything, they crossed back. Funk songs like 1975’s “Fight the Power,” a late black power anthem, and romantic ballads like “Between the Sheets” earned them a permanent place in the hearts of African Americans. The Isleys’ songs would be sampled by rappers such as Salt ’n’ Pepa, Notorious B.I.G., and Ice Cube. A younger artist, R. Kelly, refashioned singer Ronald Isley in music videos as a gangster character named Mr. Biggs. In 2003, with Kelly’s help and a black public whose buying power could now be measured in bar-code scans rather than the rock-biased record-store estimates, the Isley Brothers album Body Kiss debuted in Billboard at number 1, more than forty years after their first hit.

The Isley Brothers’ journey from a cross-racial following to a mostly black one challenges a still too commonplace assumption: that countercultural rock music, after it emerged proclaiming “Born to Be Wild” and “Sympathy for the Devil,” pursued within its quest for freedom ideals of integration and civil rights.3 Instead, rock’s commercial development, into a genre formatted through FM radio’s album-oriented rock (AOR) stations, segregated sonic rebellion. But this is only part of the story of the Isleys—and of black pop music in the rock era. As rock radio evolved in the 1970s, so too did black-oriented radio, which though rarely black-owned and increasingly corporate in its “urban contemporary” presentation—with strong ties to black-music divisions of major record labels—became an institutional bastion of overtly African American expression. Between these two genre formats could be found crossover formats, Top 40 and adult contemporary (AC), which played black performers but rarely songs with ideological messages or a racialized address. Chronicling the Isley Brothers from the 1950s to 2000s positions rock and roll, rhythm and blues (R&B), and Top 40 as three sometimes joined, sometimes clashing long histories. The relationship of race, rock, and radio was unstable and contradictory long before a Chicago prom appeared in the New York Times.

Accounts of how this played out have varied significantly. Those who print the legend correlate Elvis Presley and Martin Luther King Jr. and conclude that “the new ‘crossover’ music of rock ’n’ roll challenged the color line,” that “white people and black people came together to celebrate music powerful enough to break down ancient walls.” Others wonder why, then, by 1985 a Black Rock Coalition needed to insist that African Americans had a place within rock: “In the post–civil rights era United States,” Maureen Mahon tells us, “an interest in rock music marks an African American as someone who has either misunderstood which music is appropriate for his or her consumption or has abandoned black culture by investing in what is perceived as a white music form.” Peter Guralnick’s classic history of soul makes pivotal King’s 1968 murder, shattering the integrationist spirit of “sweet soul music” and replacing it with James Brown’s “Say It Loud (I’m Black and I’m Proud).” But Paul Gilroy, Nelson George, and Mark Anthony Neal, key theorists of soul culture, believe the real letdown was corporate commodification—Gilroy says television’s Soul Train “belongs to your American apartheid,” George blames urban contemporary broadcasting in the 1970s and 1980s, and Neal calls “Rhythm Bullshit” on the effects of radio mergers in the 1990s.4

My intent is to let the experience of the Isley Brothers tell a story in line with historians who now speak of a “long civil rights movement,” to recognize that the 1950s’ and 1960s’ overturning of southern Jim Crow laws was only one aspect of a contestation that began earlier, lasted longer, and was equally northern.5 From this perspective, the bifurcation of R&B and rock is not primarily a story about a shattered civil rights dream. And the growth of R&B as its own category is at least as important. African Americans, well before and long after the movement peaked, sought culturally unifying but commercially viable music against ever mutating barriers, including white appropriation. Research on the Decatur Street scene in 1910s Atlanta finds black domestic workers ballin’ the jack to sounds that might have been ragtime or blues—musicology mattered less than that these working-class leisure spots were a “Negro playland” that, while open to all, had an “African majority.” The biggest Atlanta club, the Eighty One Theater, helped anchor a black-oriented vaudeville entertainment circuit, the Theater Owners Booking Association. The TOBA’s nickname was “Tough on Black Asses,” and theater owners were white. Still, this “chitlin’ circuit” created networks where professional music existed on primarily nonwhite terms. From the Eighty One alone came blues singer Bessie Smith, gospel pioneer Thomas Dorsey, and Perry Bradford, who’d write and produce the first blues recorded by an African American, Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues.”6

It is hardly a stretch to see continuities between the world Bradford evokes in his “Original Black Bottom Dance” (“started in Georgia and it went to France / It’s got everybody in a trance”) and Jermaine Dupri and Ludacris, some ninety years later, singing “Welcome to Atlanta” (“big beats, hit streets”). R&B as a format operated much like the chitlin’ circuit. It was always underfunded, high ratings not translating into high ad sales and station owners said to turn to it as a last resort. Indianapolis assistant station manager Amos Brown told Radio Records in 1979, “One thing Black stations should understand is that their advertisers don’t want to be there. If an advertiser could, he’d want to be on the number one, two or three radio stations in the market. They don’t trust it, they don’t understand it, they still don’t believe that black people in this day and age control billions of dollars in the country.” Radio analyst Sean Ross complained that owners tried to “run a successful Black/Urban station for next to nothing.”7

Nonetheless, within the R&B format, black music was defined by majority black audiences, in particular female audiences, in a manner that Top 40 and certainly rock radio did not allow for. “In black culture,” African American studies scholar James Snead wrote in an influential essay, “the thing (the ritual, the dance, the beat)” has to be “there for you to pick it up when you come back to get it.” It’s striking how well this describes the presumptions of formatted radio listening: the sound, and sense of being personally addressed, must be there each time the channel comes on. Despite its relative weakness in radio generally, black-oriented radio institutionalized R&B in just such a fashion. History recast black music in other ways: the civil rights pinnacle celebrated in soul, the depoliticized sounds of disco, the postindustrial critique of racial uplift delivered by hip-hop. “Radio stations, I question their blackness,” Public Enemy rapper Chuck D thundered in 1987. “They call themselves black but we’ll see if they play this.” But R&B remained underneath it all, the “changing same” that Amiri Baraka described. Its historic role was to mediate the process that Adam Green calls “selling the race” and Guthrie Ramsey terms “Afromodernism”: an attempt to reconcile commerce and community, folk roots and pop spectacle, secular and sacred.8

The advantage of the Isley Brothers’ elongated career is that it condenses into a single case study of R&B’s position within a multigenerational narrative and interweave of music formats. Though the Isleys were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1992, few rank them as great innovators. They were a savvy act, changing with the times. But as George Lipsitz appreciates, “As entertainers whose livelihood depended on purchases by the public, the Isley Brothers (and many other musicians like them) mined the memories, experiences, and aspirations of their audiences to build engagement and investment in the music they made.” Their hits proved iconic, sealing pivotal social moments into popular memory.9

“Shout”: R&B and Afromodernism

The great hit song that launched the Isley Brothers, “Shout,” was recorded in New York in 1959 for the major label RCA. Ronald Isley begins a cappella, bending out well in the preacherly fashion his early idol Clyde McPhatter had taught him, then saying, “you know you make me want to”—and here his brothers join up and the band kicks in—“shout!” He continues to call out phrases, which they echo, and then reaches for a high falsetto. A minute in, there is a full downshift and wiggling in tempo, his brothers fall out, and a keyboard emerges, played not by a studio musician but by Herman Stephens, from the family’s Baptist church in Cincinnati. The song’s second half on 45 (joined in most album versions) becomes a virtual religious service, with claps in response to sermonizing and audience participation sections that lower and raise the volume. The song is a clamorous participatory ritual, uncannily distilled into a recording. “Soul music” as a phrase existed only in jazz in 1959, but by fusing sanctified and secular, African American inheritances and commercial pop, the Isleys delivered a key prototype.

How did “Shout” happen? The emergence of “rhythm and blues,” a coinage of Billboard in 1949, and the equally new concept of black-oriented commercial radio reflected a fundamental shift in African American identity: the presence, as of World War II, of a majority urban population, often migrated from rural southern backgrounds, self-consciously modern in wanting the culture they could purchase to express freedoms unavailable in daily life. The result, defined as Afromodernism in Guthrie Ramsey’s important study Race Music, was heard in the electrified jump blues party music of Louis Jordan, which led to the soul crews of James Brown. But it also extended to the rhetorically classy Ebony magazine (launched in 1945), gospel music as an autonomous professional circuit, and the strategic style eclecticism of performers such as Dinah Washington, Sam Cooke, Ray Charles, and Aretha Franklin. As Ramsey writes, “If one of the legacies of nineteenth-century minstrelsy involved the public degradation of the black body in the American entertainment sphere, African Americans used this same signifier to upset a racist social order and to affirm in the public entertainment and the private sphere their culture and humanity.” “Shout” was a defining statement of Afromodernism.10

This is not, of course, how “Shout” was heard by rock and roll fans. No one has better expressed the biases of young white 1950s listeners than Jeff Greenfield, the future TV commentator, who as a teen attended interracial concerts staged by Alan Freed in Brooklyn: “Brewed in the hidden corners of black American cities, its rhythms infected white Americans, seducing them out of the kind of temperate bobby-sox passions out of which Andy Hardy films are spun. Rock and roll was elemental, savage, dripping with sex; it was just as our parents feared.”11 That, we shall see, is the view of “Shout” seen in Animal House, where it is performed for white fraternity brothers. But “Shout” as Afromodernism is different. Its rawness is skillful, rooted in church practices and professional entertainment, in an urbanity that accepts no contradiction between respectable and uninhibited, the vernacular of the South and the slickness of the North. Confronting R&B’s long history as a format puts “Shout” and the Isleys in this context.

“My father told my mother he wanted a group like The Mills Brothers,” Ronald Isley remembered, “and right away she had four boys!” O’Kelly Isley was a North Carolina native and vaudeville veteran who had sung with a touring stage revue, the Brown Skin Models, before finding God and spiritual music; he married Sallye Bernice of Georgia, a church pianist and choir singer. In short succession, four sons were born: O’Kelly (1937), Rudolph (1939), Ronald (1941), and Vernon (1942). Two younger brothers would follow, with Ernie (1952) and Marvin (1953) destined to join their siblings in the 1970s, and Vernon died young, but for now O’Kelly had his quartet.12

As for his role models, the Mills Brothers, hailing from near Cincinnati, where the Isleys came to live during World War II, had used their close-knit harmonies to simulate madcap jazz ensembles, croon smooth ballads, and cross every racial boundary marker in American entertainment. They appeared on Rudy Vallee’s radio program, recorded duets with Bing Crosby, and were filmed for The Big Broadcast. Their biggest hit, “Paper Doll,” promoted with a Soundie (an early jukebox-type music video), topped the pop charts and sold millions from 1943 to 1944. Deriving from barbershop quartets, influencing jubilee gospel quartets, and anticipating the street-corner vocal groups of R&B, the Mills Brothers exemplified African American “middle of the road,” or MOR, with hits into the 1960s.13

If the Mills Brothers were O’Kelly’s paradigm, Sallye Bernice steered her sons toward the “gospel highway” of church choirs, talent competitions, and sheet-music publishing that Thomas Dorsey and his partner Sallie Martin had created in Chicago and spread through black urban America. It was the sacred version of the chitlin’ circuit, but with more room for women as performers and entrepreneurs. Gospel acts dealt with “notoriously crooked” promoters and united audiences spanning generat...