![]()

CHAPTER 1

Sex Itself

Human genomes are 99.9 percent identical—with one prominent exception: instead of a matching pair of X chromosomes, men carry a single X, coupled with a small chromosome called the Y. Today, with the genome sequences of the human X and Y chromosomes at hand, geneticists are searching anew for the elements of maleness and femaleness—for what the famous American fly geneticist Thomas Hunt Morgan in 1916 called “sex itself.”1 With knowledge of the genes animating sex differences, researchers hope to aid medical understanding of sex-specific diseases and uncover the foundations of male-female differences in cognition, intelligence, and behavior. Some suggest that we will at last discover what it means to be a male or a female. Some hope that genomics will help us measure, quantitatively and precisely, differences between men and women. According to commentators in the March 2005 issue of Nature, which announced the publication of the complete sequence of the human X chromosome, these differences will likely prove to be greater than ever thought.2

Tracking the emergence of a new and distinctive way of thinking about sex represented by the unalterable, simple, and visually compelling binary of the X and Y chromosomes, this book examines the interaction between cultural gender norms and genetic theories of sex from the beginning of the twentieth century to the present postgenomic age. The past century has seen enormous shifts in the biological model of sex. At the turn of the twentieth century, the metabolic theory ruled the day. Biologists believed that metabolic rate mediated masculinity and femininity and determined whether a newly fertilized egg became male or female.3 The hormonal model emerged in the 1920s and dominated the midcentury. The sex hormones, pharmaceutically powerful, quantitative, and malleable agents of sexual behavior and secondary sex characters, have been the overwhelming focus of histories of twentieth-century scientific ideas about sex.4 The genetic account of sex has received far less attention.

The genetic binary of the X and Y chromosomes was discovered at the turn of the twentieth century. It entered human biomedicine with revelations of cases of human males with extra X chromosomes (XXY) and females with only one X (XO) in the 1950s. Now, with the completion of the Human Genome Project, genes and chromosomes are moving to the center of the biology of sex. As this book shows, the X and Y chromosomes, little symbols of unbreachable sex dimorphism, came to anchor a conception of sex as a biologically fixed and unalterable binary, the very conception premonitioned by Morgan’s “sex itself.”

From the earliest theories of chromosomal sex determination, to the midcentury hypothesis of the aggressive XYY supermale, the longstanding belief that the X is the “female chromosome,” and the recent claim that males and females have “different genomes,” cultural gender conceptions have influenced the direction of sex chromosome genetics. Gender has helped to shape the questions that are asked, the theories and models proposed, the research practices employed, and the descriptive language used in the field of sex chromosome research. Analyzing the history of human sex chromosomes as gendered objects of scientific knowledge, this book adds gender to our intellectual histories of human genetics, and genetics to our histories of scientific theories of sex and gender.

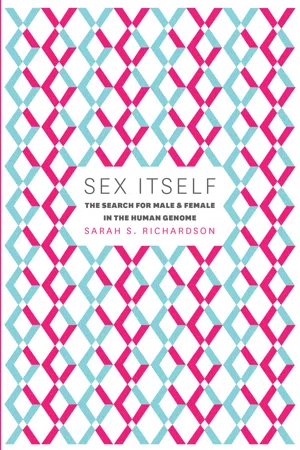

Today, scientific and popular literature on the sex chromosomes is rich with examples of the gendering of the X and Y. Humorous maps of the X and Y chromosome—pinned up on laboratory walls and always good for a laugh in an otherwise dry scientific talk—assign stereotypical female and male traits to the X and Y, from the “Jane Austen appreciation locus” to “channel flipping” (see fig. 1.1). The X is dubbed the “female chromosome,” takes the feminine pronoun “she,” and has been described as the “big sister” to “her derelict brother that is the Y” and as the “sexy” chromosome.5 The X is frequently associated with the mysteriousness and variability of the feminine, as in a 2005 Science article headlined “She Moves in Mysterious Ways” and beginning, “The human X chromosome is a study in contradictions.”6 The X is also described in traditionally gendered terms as the more “sociable,” “controlling,” “conservative,” “monotonous,” and “motherly” of the two sex chromosomes.7 Similarly, the Y is a “he” and ascribed traditional masculine qualities—“macho,” “active,” “clever,” “wily,” “dominant,” and also “degenerate,” “lazy,” and “hyperactive.”8

Figure 1.1. Humorous maps of traits on the X and Y chromosomes. Recreated by Kendal Tull-Esterbrook, with permission from the authors. The X chromosome is after an original designed by Dr. Jennifer A. Graves; the Y chromosome is after an original by Dr. Jane Gitschier.

Three common gendered tropes feature in popular and scientific writing on the sex chromosomes. This first is the portrayal of the X and Y as a heterosexual couple with traditionally gendered opposite or complementary roles and behaviors. For instance, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) geneticist David Page says, “The Y married up, the X married down. . . . The Y wants to maintain himself but doesn’t know how. He’s falling apart, like the guy who can’t manage to get a doctor’s appointment or can’t clean up the house or apartment unless his wife does it.”9 Biologist and science writer David Bainbridge narrates the evolutionary history of the X and Y as a “sad divorce,” set in motion when the “couple first stopped dancing,” after which “they almost stopped communicating completely.” The X is now an “estranged partner” of the Y, he writes, “having to resort to complex tricks.”10 Oxford University geneticist Bryan Sykes similarly describes the X and Y as having a “once happy marriage” full of “intimate exchanges” now reduced to only an occasional “kiss on the cheek.”11 A 2006 article on X-X pairing in females in Science by Pennsylvania State University geneticist Laura Carrel is headlined “‘X’-Rated Chromosomal Rendezvous.”12

Second, sex chromosome biology is often conceptualized as a war of the sexes. In Matt Ridley’s 1999 Genome: The Autobiography of a Species in 23 Chapters, the chapter on the X and Y chromosomes is titled “Conflict.” It relates a story, straight from Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus (1992), of two chromosomes locked in antagonism and never able to understand each other.13 A 2007 ScienceNOW Daily News article similarly insists on describing a finding about the Z chromosome in male birds (the equivalent of the X in humans) as demonstrating “A Genetic Battle of the Sexes,” while Bainbridge describes the lack of a second X in males as a “divisive . . . discrepancy between boys and girls,” a genetic basis for the supposed war of the sexes.14

Third, sex chromosome researchers promote the X and Y as symbols of maleness and femaleness with which individuals are expected to identify and in which they might take pride. Sykes offers the Y chromosome as a totem of male bonding, urging males to celebrate their unique Y chromosomes, and calling for them to join together to save the Y from extinction in his 2003 Adam’s Curse: A Future without Men. Females are also encouraged to identify with their Xs. Natalie Angier urges that women “must take pride in [their] X chromosomes. . . . They define femaleness.”15 The “XX Factor” is a Slate column about women’s work and life issues with the slogan “What Women Really Think” and is also the name of an annual competition for female video gamers.16 The promotional video for the US Society for Women’s Health Research, designed to convince the viewer of how very different men and women really are, is titled What a Difference an X Makes!17

The past decade has witnessed a wave of critical scholarship on the potential of the genome-sequencing projects to resurrect dangerous notions of human difference, but the focus has been more on race than gender.18 With the painful history of racial science in the background, publicly funded genome projects have supported research by historians, philosophers, and bioethicists to study the impact of new genome science on marginalized, vulnerable, or underrepresented groups. The history of sexual science—an enterprise that famously admonished that higher education could impair women’s ovaries, pronounced that women are ruled by their emotions and not their intellects, and asserted that women are developmentally arrested males halfway between men and children—holds similar cautions of the dangers of uncritical scientific constructions of sex differences.19 Yet the questions to which scholars have so carefully and urgently attended in the case of genetic research on race and ethnicity are not being asked of genetic research on sex and gender. With this book, I hope to open a conversation about the methods and models of sex difference research in a genomic age.

THE SEX CHROMOSOMES

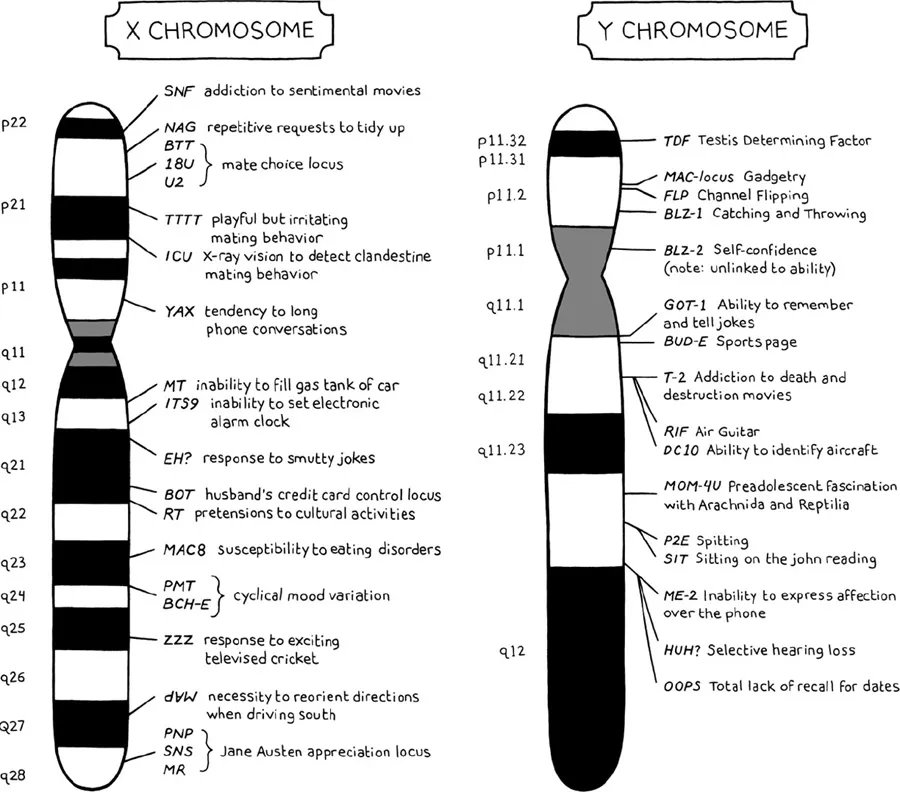

Chromosomes, housed in the nucleus of each of our cells, are packages of DNA (see fig. 1.2). Humans have 23 pairs of them. Each pair is composed of a chromosome received from the egg and the sperm. The chromosomes contain tightly coiled strands of DNA unique to each chromosome. Twenty-two of the pairs are homologous, which means that other than the small differences in gene variants that we inherit from our parents, the two chromosomes are identical. The twenty-third pair is different. In the case of males, it comprises an X partnered with the much smaller Y. Males are thus said to be “XY.” Females possess two Xs and are “XX.”

Figure 1.2. Chromosomes are packages of DNA housed in the cell nucleus. Illustration by Kendal Tull-Esterbrook; copyright Sarah S. Richardson.

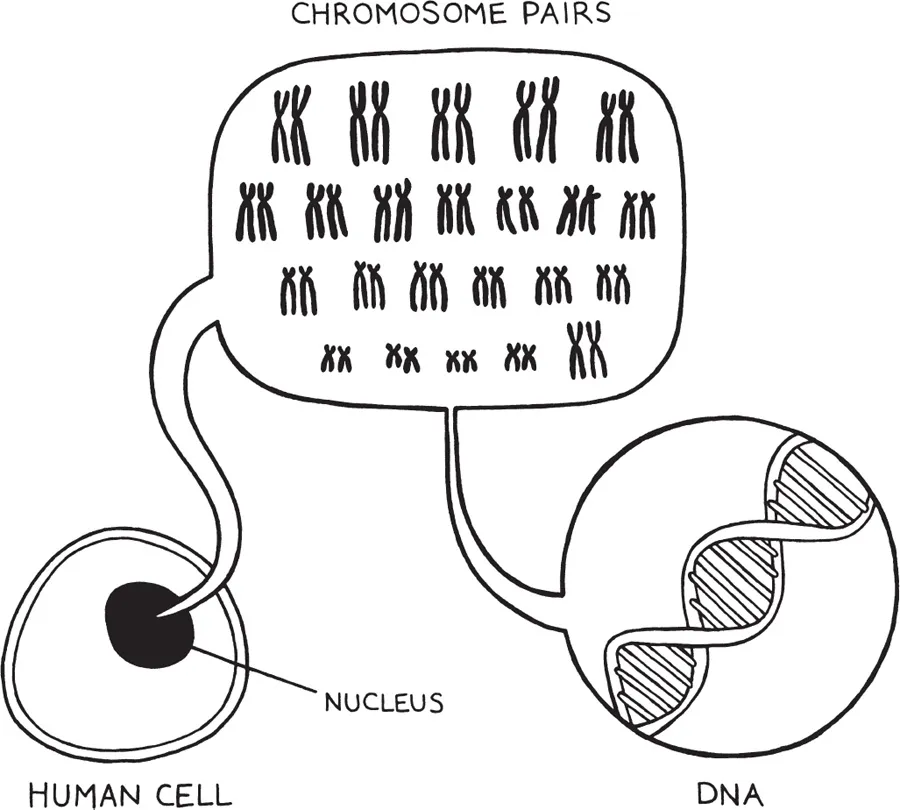

The sex chromosomes are widely recognizable symbols of genetic science. Doctors use them to indicate the sex of a fetus, and school science textbooks feature memorable clinical anomalies such as the XXY Klinefelter’s male, who has an extra X chromosome, and the XO Turner’s female, who possesses one X instead of two. Classically, reproductively viable phenotypic sex in humans has been seen as a three-step process: chromosomal and genetic initiation of gonad determination (ovaries or testes), followed by the production of the correct ratio of sex steroids (androgens and estrogens), leading to the development and differentiation of the reproductive organs and secondary sexual characters. In males, testes determination begins during fetal development (see fig. 1.3). This involves a genetic pathway requiring the SRY gene on the Y chromosome and the SOX9 gene on chromosome 17. As will be discussed in chapter 6, the genetics of female ovary determination has been less studied than that of the testes, but it too requires a sequence of genetic signals. The WNT4 gene on chromosome 1 is emerging as a crucial genetic factor in ovarian development.20

Though often described as the “female” and “male” chromosomes, there is nothing essential about the X and Y in relation to femaleness and maleness. Chromosomes are only one form of sex-determining mechanism in the natural world. Birds have sex chromosomes, but the system is the reverse of mammals. In our avian cousins, males have the duplicate larger chromosome (called ZZ), while females are heterozygous (ZW), possessing one larger and one smaller chromosome. In fruit flies, sex is determined by the ratio of X chromosomes to autosomes, rather than the presence or absence of a Y chromosome, as in mammals. For turtles and many reptiles, sex depends on the temperature of the environment during early development, not sex chromosomes. Some species have just one sex, some have three or more, and some can change sexes during their lifetimes—and this can depend purely on the arrangement of sex chromosomes, wholly on exposure to environmental factors, or on a combination of the two.

Indeed, the ambiguous and indeterminate relationship between the X, the Y, and sex will animate much of the story in this book. In principle, any chromosome may contain genes relevant to sex differences. There are also other sexed processes in the human genome, such as maternal and paternal genetic imprinting, a process by which gene variants may be active or inactive depending on the parent of origin. Nonetheless, for the past century, the sex chromosomes have been the principal objects of analysis of genetic sex research, and today they continue to dominate the landscape of genomic reasoning about sex and gender.

Figure 1.3. The relationship between sex chromosomes and sexual phenotype. Illustration by Kendal Tull-Esterbrook; copyright Sarah S. Richardson.

SEX ITSELF

In 1916, Morgan strenuously warned against thinking of the X and Y as “sex itself.” He foresaw that the prominent dimorphism of the X and Y in the human genome would become imbued with special significance in the eyes of biologists. Indeed, the quest to know the thing itself or to access the first cause would become a central theme of twentieth-century molecular science. Within this new worldview, the anatomical markers of sex and the final expression of gender identity are not themselves “sex itself,” but mere signifiers, traces, and elaborations of the genotypic dimorphism that underlies it all.

Biologists have never been under the illusion that genes and chromosomes are all there is to the biology of sex. Today, as in Morgan’s time, researchers acknowledge that human biological “sex” is not diagnosed by any single factor, but is the result of a choreography of genes, hormones, gonads, genitals, and secondary sex characters. Today, academic sexologists typically distinguish between chromosomal sex, gonadal sex, hormonal sex, genital sex, and sexual identity. Some would add sexual preference, gender identity, morphological se...