eBook - ePub

Scenes from Deep Time

Early Pictorial Representations of the Prehistoric World

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

How did the earth look in prehistoric times? Scientists and artists collaborated during the half-century prior to the publication of Darwin's Origin of Species to produce the first images of dinosaurs and the world they inhabited. Their interpretations, informed by recent fossil discoveries, were the first efforts to represent the prehistoric world based on sources other than the Bible. Martin J. S. Rudwick presents more than a hundred rare illustrations from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to explore the implications of reconstructing a past no one has ever seen.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Scenes from Deep Time by Martin J. S. Rudwick in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Science General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Creation and the Flood

Any scene from deep time embodies a fundamental problem: it must make visible what is really invisible. It must give us the illusion that we are witnesses to a scene that we cannot really see; more precisely, it must make us “virtual witnesses” to a scene that vanished long before there were any human beings to see it.1

However, this problem is only slightly more acute than that faced by an artist depicting a historical scene in a similarly “realistic” style. Whether it comes from classical or biblical history—say, the Fall of Rome or the Fall of Babylon—the picture must make its viewers believe they are seeing a plausible representation of an event that neither they nor the artist have really witnessed at all. It must make them virtual witnesses of a scene that is reconstructed from the testimony of those who did see it. In the tradition of Western pictorial art, that testimony was overwhelmingly textual in character. Knowledge of material remains—for example, of the ruins of ancient Rome—could be used to supplement the texts; but the textual evidence from the classical or biblical authors remained paramount.2 What they reported in words was translated by the artist into visual terms, according to the pictorial conventions of the time and place in which the artist was working. What was judged to be a plausible or “realistic” representation was of course relative to those shared conventions.

It is hardly surprising that the earliest scenes that can be regarded in retrospect as being from “deep time” were firmly embedded in this artistic tradition of visual representations of scenes from the human past. In early modern Europe, scholars considered that the past history of the human race was recorded more or less fragmentarily in the chronicles of all literate societies. It was the task of the science of “chronology” to compare and evaluate these records critically, to correlate the various calendars by which they were dated, and to weld them all into a single universal history.3 However, the chronologers of the seventeenth century found their task increasingly difficult, as they penetrated back in time beyond the records of ancient Greece and its temporal equivalents elsewhere. By the time they reached the Flood or Deluge, of which they believed they could detect at least some obscure testimony in the records of many ancient cultures, one such record outshone all others by its apparent clarity and detail. Of course the biblical record would have been given some privileged status anyway, because of its overarching religious role in the culture of Christendom; but it is important to recognize that most seventeenth-century scholars considered that it also deserved special attention on account of its value as history.

For the time before the Deluge, the record became even more obscure, though here too the early chapters of Genesis seemed to provide at least a bare outline of “antediluvian” characters and events. Finally, or rather, for the beginning of all things, the chronologers had to rely on the biblical narrative of Creation itself. By its very nature this could not be regarded as a human record of events, since even Adam had not been there to witness them until the sixth day of Creation. But the veracity of the record was only enhanced by its putatively divine origin.

This image of a world of limited time, in which Creation itself was not more than a few thousand years distant, was simply a part of taken-for-granted reality in early modern Europe. Like its spatial or astronomical counterpart, the “closed world” of the Ptolemaic cosmos, it was not adopted for reasons of religious prejudice, still less expressed in order to avoid ecclesiastical censorship. It embodied the generally agreed, apparently common-sense view of the world.

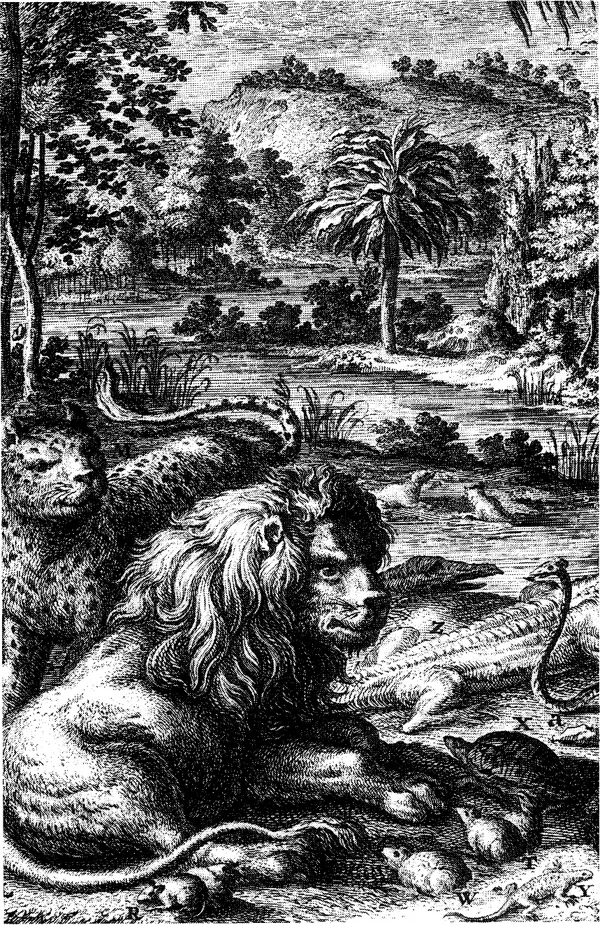

It was within this image of the world’s history that the first scenes from relatively deep time came to be designed. In Western religious art, there was a longstanding tradition of depicting episodes such as Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden and Noah’s Ark riding out the Flood, as early scenes within much longer sequences.4 In stained-glass windows or in tempera wall paintings, such cycles sought to represent visually, and thereby to make more accessible and persuasive, the Christian interpretation of cosmic history—all the way from the Creation recorded in Genesis, through the pivotal events of the life, death, and resurrection of Christ recorded in the Gospels, to the final Judgment foreshadowed in the Apocalypse. Traced from the medieval centuries into the art of the Renaissance and later periods, the pictorial conventions changed dramatically, but the program remained much the same. More significant was the invention of printing, especially the concurrent development of print-making, first in the form of woodcuts and later as copper engravings.5 This made such pictorial cycles far more widely available: they could now be studied at home, at least in more affluent homes, within the covers of a book, rather than being seen only in the local church, or on a lifetime’s pilgrimage to some more distant and more distinguished site.

For the purposes of this book, it is convenient to begin with a relatively late example of such cycles. The one chosen here is particularly appropriate, because it was masterminded by a man who was also a distinguished naturalist, and who possessed one of the finest collections of fossils in early eighteenth-century Europe. Johann Jacob Scheuchzer (1672–1733) was trained as a physician and spent most of his life in his native city of Zurich in a variety of positions that would now be regarded as broadly scientific. He traveled extensively in the Swiss Alps, at a time when exploring the more remote parts was still a hazardous undertaking, and he published voluminous works on the natural history of Switzerland. Like many naturalists at this time, he also had major interests in human history; and he published a history of his native country and edited a collection of relevant historical documents.

Those two areas of interest—natural history and civil history—came together in his work on fossils. For like many of his contemporaries, Scheuchzer believed that fossils were relics of the Deluge. They recorded the natural history of the country before the Deluge, but they also provided uniquely persuasive evidence for the reality of that distant historical event. Scheuchzer’s Herbarium of the Deluge (Herbarium Diluvianum, 1709) depicted the wide range of fossil plants in his own collection, in a way that made it a valuable reference work long after his “diluvial” interpretation had been abandoned.6 Puzzled by the total absence of human fossils, he later seized on a newly discovered specimen as being indeed that of “a man who was a witness of the Deluge” (Homo Diluvii testis; 1726); he did not live to witness its much later identification as a large amphibian!7

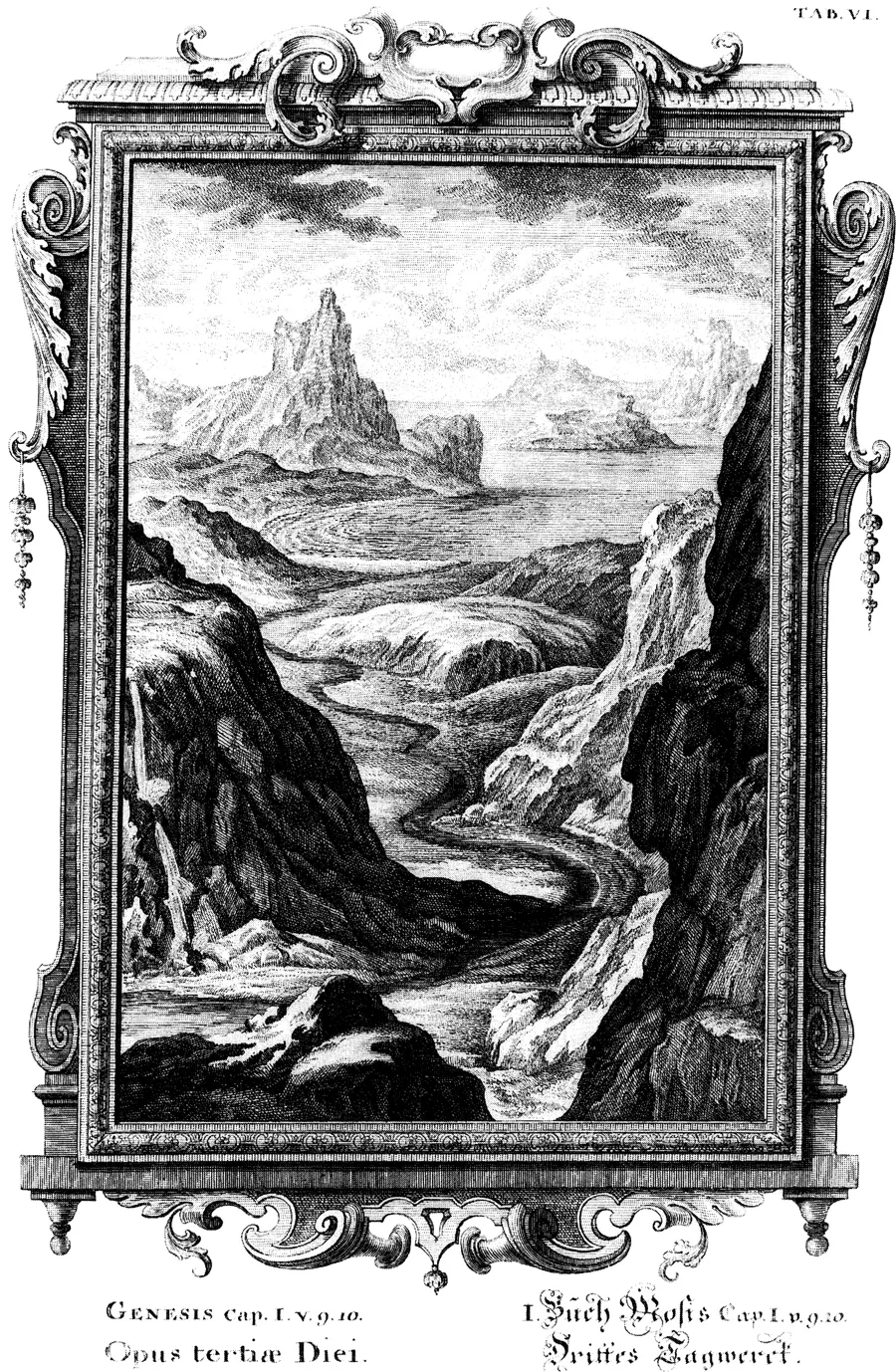

Scheuchzer’s scenes from near the beginning of time—as he and most of his contemporaries conceived it—were published in his last and largest work, Sacred Physics (Physica sacra, 1731–33). They came at the start of the sumptuous folio volumes, which were published in both Latin and French, the older and the newer international languages of science and scholarship, as well as in German, Scheuchzer’s native language. Scheuchzer’s work thereby became widely known throughout the literate world.8 The word “physics” still bore its old Aristotelian meaning and was not far from the modern sense of “science.” The work was “sacred” physics, because it sought to illustrate the biblical narrative from ancillary evidence drawn from the best science of the day. It was a massive undertaking. There were no fewer than 745 full-page copper engravings; indeed the German edition was even entitled Copper Bible (Kupfer-Bibel), in order to emphasize its illustrations. They were drawn by a team of eighteen engravers under the direction of the imperial engraver Johann Andreas Pfeffel (1674–1748), whose name was rightly given as much prominence on the title page as Scheuchzer’s. Other artists had special responsibility for the design of the elaborate baroque frames for the scenes, and even for the lettering of the captions.

The overwhelming majority of Scheuchzer’s scenes illustrate episodes from biblical history, stretching from beginning to end, from Genesis to the Apocalypse. Just as the Creation narrative was regarded as a brief prelude to the main—human—story of the world, so likewise the engravings that illustrate the Creation (and the later Deluge), several of which are reproduced here, come just from the start of a far longer sequence of scenes, covering in principle the whole of human history.

Unlike the literalism of modern fundamentalists, with their deliberate rejection of biblical scholarship, Scheuchzer’s superficially similar interpretation of the earliest chapters of the Bible reflects a mainstream tradition that in his day still embodied good plain sense. A more historical understanding of Hebraic language and imagery, theology and cosmology, as represented in early work on biblical criticism, had not yet spread widely even in scholarly circles. Scheuchzer and most of his contemporaries saw no difficulty in assuming that the Creation and the Deluge had taken place just as and when a literal reading of the texts suggested. That assumption is reflected visually in the engravings that he and Pfeffel designed to illustrate some scenes from the deepest time they could imagine.

The most important feature of the scenes that illustrate the Creation narrative is that they form a sequence that leads from initial chaos to a completed and human world. The various components of the natural world, finally including mankind too, are brought in turn onto the stage on which the drama of human redemption is to be played out. However, although Scheuchzer himself uses the traditional metaphor of the “theatre of the world” (see text 4), the elaborate decorative frames to these scenes suggest even more forcefully that they were to be viewed as a sequence of pictures, set out as if along the walls of a gallery, although in fact between the covers of a book.

The first pictures, of initial chaos and the creation of light, are depicted from a cosmic, not a terrestrial viewpoint—perhaps a divine view, but in any case certainly not a human one. The selection reproduced here thus starts with two scenes from the third day of Creation (figs. 1, 2; text 1). They illustrate the world just before and just after the creation of plant life. Before, the world is bare and ugly, yet also like a well-tilled plant nursery, ready and able to sustain a fertile world of plants. After, it is lush, beautiful, and full of color. Yet—as Scheuchzer is careful to add, in order to counter any suggestion of materialism—it is not the soil itself that has the power to produce all these varied plants, but God alone.

Figure 1. “The Work of the Third Day”: t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Frontispiece

- Title Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1. Creation and the Flood

- 2. Keyholes into the Past

- 3. Monsters of the Ancient World

- 4. A First Sequence of Scenes

- 5. Domesticating the Monsters

- 6. The Genre Established

- 7. Making Sense of It All

- Notes

- Sources for Figures and Texts

- Bibliography

- Index