![]()

Part One

ACTS OF GOD, DEEDS OF MEN

In the war zone, where one cannot escape situating the texts under discussion, a variety of speech act continues to wage battle. It turns out that we have stumbled into a twilight zone between knowing and not knowing, a space where utterances (“as well Publick as Private”) create myths whose transmissions are primarily oral. They operate according to a logic of contagion, communicating, like certain diseases, a kind of uncontrollable proliferation.

AVITAL RONELL, “Street-Talk”

![]()

1

Enlightenment and the Plague

On May 25, 1720, the ship Grand Saint-Antoine sailed into Marseilles, carrying a full cargo of silks, cotton, and bales of wool she had taken on board in Smyrna and Cyprus. Her captain, Jean-Baptiste Chataud, showed the port officials his patentes nettes, letters certifying that medical authorities had inspected the ship in her various ports of call, and found no sign of dangerous disease. There were a few warning signs, however: the Grand Saint-Antoine had lost five men during her voyage: three sailors, a passenger from Turkey, and the ship’s own surgeon. Authorities in Livorno had forbidden the ship to dock, scrawling on the back of Tripoli’s patente nette that all precautionary measures should be taken when the ship reached her final destination.

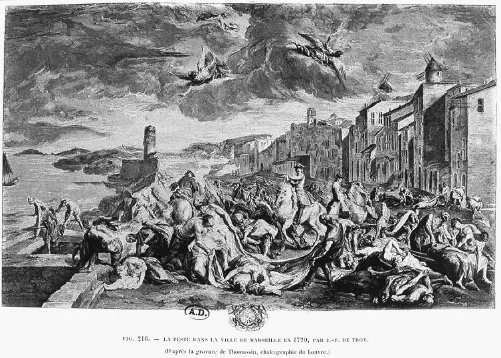

Upon arriving in Marseilles, the Grand Saint-Antoine’s cargo was put through routine disinfection procedures, and a two-week quarantine was imposed on her crew: not unusual for a ship coming from the Middle East. But the Grand Saint-Antoine also carried the plague that would devastate Marseilles over the following year, causing more than forty thousand deaths in the city alone.1 Spreading to the cities of Aix and Toulon, the disease cut a swath of fear that would haunt political and medical authorities for years to come.

In The Theater and Its Double, Antonin Artaud gives a memorable account of the epidemic that swept Marseilles after the arrival of the Grand Saint-Antoine, describing the plague as a disease that challenged all ancient and modern scientific explanations. He views the plague’s symptoms as manifestations of an extreme disorder that inscribed on the body the signs of an untamed chaos:

[The victim] is seized by a terrible fatigue, the fatigue of a centralized magnetic suction, of his molecules divided and drawn toward their annihilation. . . . His pulse, which at times slows down to a shadow of itself, a mere virtuality of a pulse, at others races after the boiling of the fever within, consonant with the streaming aberration of his mind. . . . [T]he body fluids, furrowed like the earth struck by lightning, like lava kneaded by subterranean forces, search for an outlet. The fieriest point is formed at the center of each spot; around these points the skin rises in blisters like air bubbles under the surface of lava, and these blisters are surrounded by circles, of which the outermost, like Saturn’s ring around the incandescent planet, indicates the extreme limit of a bubo.2

Fig. 1. Jean-François de Troy, La Peste dans la ville de Marseille en 1720, par J.-F. de Troy (The plague in the city of Marseille in 1720, by Jean-François of Troy). After an engraving by Simon Thomassin. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Photograph: © Pierre Barbier/Roger-Viollet/The Image Works.

But for all the telluric violence suffered by the plague victims, Artaud notes, autopsies revealed no internal lesions:

Whatever may be the errors of historians or physicians concerning the plague, I believe we can agree upon the idea of a malady that would be a kind of psychic entity and would not be carried by a virus. If one wished to analyze closely all the facts of plague contagion that history or even memoirs provide us with, it would be difficult to isolate one actually verified instance of contagion by contact.3

Alexandre Yersin’s 1894 discovery of the bacillus that caused the plague, Artaud argues, hardly explained the true nature of the disease. Artaud proposes instead to explore the plague’s “spiritual physiognomy,” one that underlines the “spiritual freedom” with which the plague develops, “without rats, without microbes, and without contact” and from which he would deduce “the somber and absolute action of a spectacle.”4

Artaud’s mystical reading of the disease duplicates, in fact, many of the observations of witnesses to the Marseilles 1720 epidemic. What Artaud calls the “frenzy” of the last of the living, and “the surge of erotic fever” that seized the recovered victims, also impressed witnesses in Marseilles: “Many people thought that the plague excited love, and that there was an extraordinary disposition to procreate, in order to replace so many people who had died,” wrote one observer. “The hospitals themselves have become tabernacles for sinners,” wrote a priest, “death is almost always the result of fornication, adultery, and rape.”5 The path of devastation caused by the disease and the disorders that followed its outbreak were watched with growing anxiety by the rest of Europe. More than the disaster of Lisbon, the plague of Marseilles set the stage for the most important debates of the Age of Reason, calling attention to the radical limits of scientific knowledge and human understanding.

A PROTEAN DISEASE

By the time the Chevalier de Jaucourt—one of Diderot’s closest collaborators—wrote the articles dedicated to the plague in the Encyclopédie, Europe had been free of the disease for a number of years. Yet fear of the plague was intense. Though it has been assumed that by the 1750s scientific discourse had long eclipsed the superstition and legends of old times, it is worth noting that the Encyclopédie’s articles on the plague describe at length the ancient terrors and all the obscure anxieties that had long made the plague the paradigm of all diseases.

Jaucourt defines the plague as “an epidemic disease, contagious, very acute, and caused by subtle venom disseminated through the air.” After detailed descriptions of the disease’s “terrible rage,” Jaucourt concludes that the best protection from the plague (also reflected in a much-quoted proverb) is to flee its devastation: Mox, longe, tarde, cede, recede, redi (flee promptly, go far away, return a long time afterward). The elusive disease, he writes, strikes rich and poor indiscriminately, old and young alike, and it produces an infinite diversity of contradictory symptoms. Antoine Furetière’s Dictionnaire universel had already noted that the signs of the plague were so varied that “one can hardly find two sick men with the same symptoms.”6 The patient’s pulse may be “strong” or “weak and frequent,” writes Jaucourt; it is “at times even, at times uneven.” Some patients are feverish and exhausted while others remain strong; some suffer hemorrhages “through the nose or the mouth, through the eyes, or the ears, or the penis or the womb”; some sweat blood all over their bodies, experiencing “exterior cold with fire inside.” The patients’ urine may remain “unchanged,” or “very different”; it may be “clear or cloudy,” or again “bloody.” Diseased bodies may be covered with purple or black spots, which may be “sometimes numerous, sometimes few in number, sometimes large, sometimes small, sometimes exactly round, sometimes on one part of the body, sometimes on another, sometimes all over the body.” Although the plague’s “venom” acts “very differently” from that of other diseases, it seems to combine them all in the dizzying array of its symptoms. Jaucourt faithfully echoes Guy de la Brosse’s 1623 treatise, which stated: “A venom is nothing other than a malignant substance, stamped with the image of death and the power to destroy the subject against whom it acts: the plague’s venom is the most general of all venoms and acts in accord with [il a convenance avec] all of them; indeed it contains them all.”7 As a later commentator would put it, “The plague exhibits the symptoms of all the other diseases.”8

Jaucourt’s description of the plague’s symptoms follows a complex and contradictory list of its causes: the plague may be carried by the southern winds, he wrote, yet be caused by an absence of wind; it may result from excessive cold or excessive heat, very dry or very humid air. Anticipating Artaud’s remarks that “the Grand Saint-Antoine did not bring the plague to Marseilles” because “it was already there,” Jaucourt notes that the seeds of the plague could remain hidden for a very long time in infected bodies. “Thus one saw persons fall dead, and suddenly struck with the plague when simply opening infected bales, unloaded from ships that came from the Orient.” Everything conspires to upset the body. “A poor diet and an abuse of non-natural things, either in the air or in the food, or lack of exercise may greatly contribute to attracting this disease.” When simply breathing or eating or famine can kill, and the wind or the lack of it can infest a city with the plague, the outlook is bleak. Jaucourt readily admits the defeat of men in his paragraph entitled “Prognosis”:

It is all the more unfortunate that no one has yet uncovered the cause or the cure of this terrible disease, although we have a number of complete treatises on its cause and the ways to treat it. It is indeed the cruelest of all evils. All shudder at the name of the disease alone; this fear is but too justified; a thousand times more fatal than war, it kills more people than fire and sword. One reflects with horror on its terrible devastation; it carries off entire families, mature men, adults, children still in their cradle; even those who are still hidden in their mother’s womb, although they appear to be protected, incur the same fate; it is even more pernicious for pregnant women, and if their child is born, will not to live but die; the air is fatal to him. The air is more fatal still for those with a strong and vigorous constitution. The plague destroys relations among citizens, communication among parents; it breaks the strongest bonds of families and society. In the face of so many calamities, men are continuously on the verge of falling into despair.

With no cure in sight, and no effective ways of containing the disease, Jaucourt focuses on the plague’s most serious legacy: by breaking men’s natural bonds—those that unite family members—the plague threatens the social project at the core of the philosophes’ program. Once communications are disrupted, men are plunged into the isolation of an earlier age, deprived of the care and compassion of others. When Jaucourt writes that the plague is more deadly than any war, he alludes not only to the number who died, but to the more radical undoing of the social ties without which progress cannot be measured or secured. The plague thus signals a disruption more extreme than the symptoms that transform and disfigure the diseased body. It serves as a dark reminder that man’s domination of nature, for all its realized ambitions, is at the mercy of the winds.

In one of their more trenchant definitions, Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno define the program of Enlightenment as “the disenchantment of the world; the dissolution of myths and the substitution of knowledge for fancy.” The mastering of matter, the regulated ordering of the natural world that formed the centerpiece of Enlightenment philosophy, they argue, left no room for the multitude of deities and hidden spirits who alternately protected and threatened mankind. “There was to be no mystery—which means, too, no wish to reveal mystery.” Man’s sovereignty over the natural world was to be secured through a form of knowledge that organized nature, through the objectifying act of naming, classifying, and “the regulative thought without whose fixed distinctions universal truths cannot exist.”9 The endless pursuit of knowledge that arose out of a terror of the unknown would thus achieve a double goal: to insure man’s freedom from fear and to secure his domination of the physical world.

From this perspective, Diderot and D’Alembert’s Encyclopédie has been justifiably described as Enlightenment’s consummate project. But in the Encyclopédie, too, the search for knowledge battles its own demons, disclosing in many ways the fears that restricted its triumph. The entries on the plague betray not just the limitations of man’s extant knowledge, but also a more pervasive fascination with the inchoate world man sought to dominate and to rationalize. For the plague defies enlightenment, and the disease’s essential contradictions return the world of men to untamed disorder. Jean-Jérôme Pestalozzi had identified the plague as the very space where the mind encounters its greatest challenge and runs the risk of being “shipwrecked,” for “the idea of the plague is so terrifying that it weakens judgment.”10

Certainly there is a rational system at work in the Encyclopédie description: Jaucourt lists four forms of the plague and six different ways of identifying it; he separates remedies into two categories, preservative and therapeutic. The list of herbal remedies is quasi-exhaustive, though not determined by any form of effectiveness: Jaucourt is careful to include a potion made with blessed thistle as well as the “celestial theriac” (a preparation made with opium and viper’s flesh, praised by Galen, and thought to have protected Mithridates from poisons). He also reviews the common medical practices, describing the physicians’ conflicting opinions, but his long piece ends with one of the Encyclopédie’s bleakest notes: “One is forced to conclude from everything that has been said about the plague that this disease is totally unknown to us as far as treatment and causes; and also that experience has only instructed us about its disastrous effects.”

In his article Jaucourt states that the 1720–21 plague of Marseilles killed approximately fifty thousand people in the city alone and “produced more than 200 volumes of treatises.” Among these was the Lettre de M*** à M. S*** à Nismes, written in Marseilles during the epidemic and which summed up the state of current medical knowledge: “The Plague is one of those impenetrable mysteries that defy reason.”11 At the time Jaucourt was writing, the plague remained a real threat. But apart from inspiring a legitimate fear, the plague represents the ultimate disorder, one that negates or reverses all measure of human progress. The plague is unpredictable, identifiable only by its defiance of all definition, recognizable only in that it simulates all other disorders. The plague can be located at the space where the very distinction between order and disorder ceases to be meaningful: a body exhibiting no symptoms and a body exhibiting all symptoms are equally susceptible of carrying the disease. By its nature, the plague involves more than human concerns; it implicates far greater forces of radical disruption.

COSMIC UPHEAVALS

When discussing sources of the plague, authors evoked heaven and hell, cosmic configurations and the bowels of the earth. Jaucourt, too, followed in a long tradition when he ...