![]()

BOOK THREE

The Establishment of an International Civilization

All truth is a shadow except the last, except the utmost; yet every truth is true in its own kind. It is substance in its own place, though it be but shadow in another place….

—Isaac Pennington

![]()

PROLOGUE TO BOOK THREE

The Middle Periods of Islamicate history

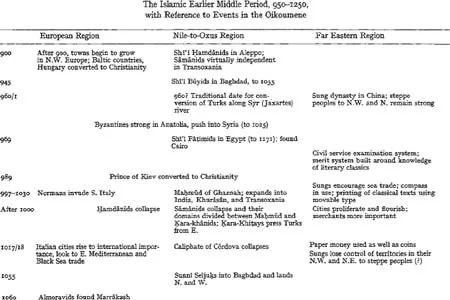

After 945 CE, the most characteristic traits of the classical ‘Abbâsî world, with its magnificent caliphal empire and its Arabic-language culture, were gradually altered so greatly that we must set off a major new era. The world of al-Manṣur, of Hârûn al-Rashîd, of al-Ma’mûn, still readily discernible in its outlines in the time of al-Muqtadir (908–932), was scarcely recognizable five or six generations later. Baghdad gradually became a provincial town and the very name of the caliphate eventually disappeared. During the five centuries after 945, the former society of the caliphate was replaced by a constantly expanding, linguistically and culturally international society ruled by numerous independent governments. This society was not held together by a single political order or a single language of culture. Yet it did remain, consciously and effectively, a single historical whole. In its time, this international Islamicate society was certainly the most widely spread and influential society on the globe. (We shall refer to the period before about 1250 as the Earlier Middle Period; to the period from then to about 1500 as the Later Middle Period.)

So far as there has been any common image of Islamicate culture, it has tended to be that of the Middle Periods—the periods after the pre-Islamic traditions in the Nile-to-Oxus region had died out (with the decline of the dhimmî population to markedly minority status), but before the Oikoumenic context (in terms of which the Islamicate culture was formed) began to be disrupted by the basic social transformation of one of its regions, the Occident. Taken narrowly, this means the time between the mid-tenth century at the collapse of the classical caliphate, under whose auspices the culture had been taking form, and the end of the fifteenth century, when a new world geographical balance gave its first intimations with the opening up of the wider oceans by Occidentals. The period of the High Caliphate tends to be seen through the image formed of it in the Middle Periods; those elements of its culture are regarded as normative that were warranted sound by later writers. More important, the problems that we have seen as distinctive of the Islamicate culture as such—the problems of political legitimation, of aesthetic creativity, of transcendence and immanence in religious understanding, of the social role of natural science and philosophy—these become fully focused only in the Middle Periods.

This way of seeing Islamicate culture is partly legitimate. To the end of the High Caliphal Period, the Islamicate culture was still in process of formation; it was still winning the population to Islam and transforming the Irano-Semitic traditions into the new form which only after 945 was ready to be carried through large parts of the hemisphere. And by the sixteenth century, quite apart from the first glimmerings of the Occidental transformation yet to come, new tendencies within Islamdom had reached a point where—at least in the three main empires then formed—in many ways, the problems we see at the start of the Middle Periods were at least transposed; even before being superseded by the radically new situation in the Oikoumene that supervened by the eighteenth century. The Middle Periods form a unity which encompasses the bulk of the time of fully Islamicate life. But it must be recognized that the Earlier Middle Period, up to the mid-thirteenth century, differed in its historical conditions rather importantly from the Later Middle Period, the period after the Mongol conquest had introduced new political resources, and the rather sudden collapse of the previously expanding Chinese economy produced—or reflected—a deterioration in the mercantile prosperity of the mid-Arid Zone. What was to be so different in the sixteenth century was well launched in the Later Middle Period.

The Earlier Middle Period was relatively prosperous. By Sung times (which began about the end of the High Caliphal Period), the Chinese economy was moving from a primarily commercial expansiveness into the early stage of a major industrial revolution, in which industrial investment was increasing at a fast and accelerating rate in certain areas, especially in the north, while in the south new methods were multiplying the agricultural productivity. The Chinese gold supply multiplied enormously with new mines opened up, and its trade to the Southern Seas (the Indian Ocean and the adjoining seas eastward) naturally increased in quantity and quality as well. Conceivably in part in response to the increased supply of gold, traceable to China, the pace of commerce and of urban activity was speeded up elsewhere also, most notably in the Occident of Europe, itself newly intensifying agricultural exploitation of its cold and boggy north by use of the mouldboard plough. In such circumstances, the Islamicate lands, still at the crossroads of hemispheric commerce, would find their commercial tendencies, over against the agrarian, still further reinforced; the results were not necessarily the most favourable, in the long run, even for commerce, yet they would allow the Muslims to demonstrate the strength and expansiveness of their social order.

The precariousness of agrarianate prosperity

Opportunities for cultural expression within a society are increased with the diversity and differentiation of social institutions through which individuals can find expression. Institutional differentiation, in turn, depends on a high level of investment, not only in the ordinary economic sense but in the sense of investment of human time—of specialized effort and concern—such as makes possible, for instance, cumulative investigation in science. But high investment presupposes prosperity, in the sense not merely of a well-fed peasantry (though in the long run this may be crucial) but of a substantial surplus available for other classes, allowing them both funds and leisure to meet specialized needs. Hence while prosperity cannot assure cultural creativity, in the long run it is a presupposition for it.

The opportunities for Muslims to take full advantage of the potentialities for prosperity and creativity offered by the Oikoumenic situation were limited by a feature of any society of the agrarianate type: that is, the precariousness of any prosperity, and of the complexity of institutions that tends to come with sustained prosperity, if it rose above a minimum institutional level. Once an urban-rural symbiosis was achieved on a subsistence level, so that agriculture could hardly proceed normally without the intervention of urban products and even urban management, almost no historical vicissitude short of a general natural disaster was likely to reduce the society to a less complex level than that. But many events might ruin any further complexity, beyond this level, that might have arisen in a society, any complexity of institutions either imaginative or especially material; and might force the society (at least locally) down nearer to the basic economic level of urban-rural symbiosis.

Massive assault from less developed areas, whose masters were not prepared to maintain the sophisticated pattern of expectations that complex institutions depend on, could reduce the level of intellectual and economic investment and with it the level of institutional complexity of a more developed area, if that area was not so highly developed as to possess unquestionably stronger force than peoples less developed. Gibbon noted this point in comparing the predicament of the agrarianate-level Roman empire with the Occident of his day, which could not be conquered except by people who had themselves adopted its technical level. As Gibbon also noted, internal pressures also could reduce the level of complexity. Spiritual, social, or political imbalances might cripple a ruling élite and its privileged culture in several ways: they could evoke outright disaffection in less privileged classes—a disaffection that might be expressed in a drive for social and spiritual conformity to populistic standards, as well as in outright rebellion; or they could result in paralysis within the ruling élites themselves, which could hasten political collapse and military devastation. Then could emerge a militarized polity, with despotism at the point of military power and anarchy at the margins, neither of which served to support delicate balances among institutions.

Complex institutions might survive many a conquest and much serious internal tension, and more often than not the ravages of warfare or the damages of political mismanagement could be repaired if they did not recur too continuously for too long. But in the long run, such resiliency depended on a high level of prosperity, which in turn depended on a balance of many favourable circumstances which were not necessarily self-perpetuating. Too much political failure could undermine the very resources with which ordinary political failure could be counteracted. The disturbance of this balance in any way could lower the level of social complexity or even occasionally reduce it, at least locally, to the minimum economic base-level of society of the agrarianate order.

To some degree, in some periods and areas in Islamdom in the Middle Periods, this precariousness of agrarianate-level prosperity did make itself felt. On the whole, the prosperity of much of Islamdom evidently declined especially in the later part of the Middle Periods, and a limit was presumably put to further development of institutional complexity. In some cases, there was a retrogression; though the impression that has been prevalent among historians, that there was a general retrogression proceeding through the Middle Periods, is probably incorrect. We have far too little evidence, as yet, to define precisely what happened. In any case, there was clearly no economic expansion within most Muslim lands comparable to what took place in western Europe or in China during the first part of the Middle Periods. This fact forces the student of the society to confront two questions. First, the great political question, in many cases, must be: how was the inherent threat of political disintegration to be met? Second, if any general consequences of hemispheric economic activity are to be looked for, we must often inquire what sorts of social orientation were encouraged as a result in the mid-Arid Zone, rather than expecting an overall higher level of investment and of institutional differentiation.

But though such questions must repeatedly be posed, economic precariousness is not yet the same as general economic decadence. Documentable decline in prosperity often turns out to have been local rather than general. Moreover, the effect of any economic decline on cultural activity and institutional complexity may be temporary; if a new (lower) level of resources is stabilized, prosperity on that base can again be a very effective foundation for cultural activity. It must be recognized that, at least in some fields, effectively high levels of prosperity were often reached in Islamdom. An agrarianate economic base-level was almost never fully reverted to, and even in the most unprosperous periods and regions a certain amount even of economic development was taking place. Meanwhile, in many parts of Islamdom some portions of the Middle Periods were very prosperous indeed, even if sometimes on a quantitatively narrower base than once. Such prosperity led to high creativity; probably at least as high as in most periods and most areas of the Oikoumene before the Modern Technical Age.

On cultural unity

Between 950 and 1100 the new society of the Middle Periods was taking form. A time of disintegration for the classical ‘Abbâsî patterns was thus a time of institutional creativity from the perspective of the Middle Periods themselves. By the beginning of the twelfth century, the main foundations of the new order had been laid; between 1100 and 1250 it flowered, coming to its best in those fields of action most distinctive of it.

This society was at the same time one and many. After the decline of the caliphal power, and with the subsequent rapid enlargement of the Dâral-Islâm, not only Baghdad but no other one city could maintain a central cultural role. It was in this period that Islam began to expand over the hemisphere: into India and Europe, along the coasts of the Southern Seas and around the northern steppes. There came to be considerable differentiation from one Muslim region to another, each area having its own local schools of Islamicate thought, art, and so forth. In the far west, Spain and the Maghrib were often more or less united under dynasties sprung from the Berber tribes of the Maghrib hinterland; these countries had a common history, developing the art which is known from the Alhambra palace at Granada, and the philosophical school of Ibn-Ṭufayl and Ibn-Rushd (Averroës). Egypt and Syria, with other east Arab lands, were commonly united under splendid courts at Cairo; they eventually became the centre of specifically Arabic letters after the decline of the Iraq with the Mongol conquests (mid-thirteenth century). The Iranian countries developed Persian as the prime medium of culture, breaking away seriously from the standards of the High Caliphal Period, for instance in their magnificent poetry. Muslims in India, opened up to Islamicate culture soon after 1000, also used Persian, but rapidly developed their own traditions of government and of religious and social stratification, and their own centres of pilgrimage and of letters. Far northern Muslims, ranged around the Eurasian steppes, likewise formed almost a world of their own, as did the vigorous mercantile states of the southern Muslims ranged around the Indian Ocean.

Yet it cannot be said that the civilization broke up into so many separate cultures. It was held together in virtue of a common Islamicate social pattern which, by enabling members of any part of the society to be accepted as members of it anywhere else, assured the circulation of ideas and manners throughout its area. Muslims always felt themselves to be citizens of the whole Dâr al-Islâm. Representatives of the various arts and sciences moved freely, as a munificent ruler or an unkind one beckoned or pressed, from one Muslim land to another; and any man of great stature in one area was likely to be soon recognized everywhere else. Hence local cultural tendencies were continually limited and stimulated by events and ideas of an all-Muslim scope. There continued to exist a single body of interrelated traditions, developed in mutual interaction throughout Islamdom. Not only the cultural dialogue that was Islam as such, but most of the dialogues that had been refocused under its auspices in the Arabic language, continued effective even when more than one language came to be used and Arabic was restricted, in the greater part of Islamdom, to specialized scholarly purposes.

But the unity of the expanded Islamdom of the Middle Periods did not hold in so many dimensions of culture as it had, in the greater part of Islamdom, under the High Caliphate. The Islamicate society as a whole had initially been a phase of the Irano-Semitic society between Nile and Oxus, building on the everyday cultural patterns of its underlying village and town life. In the Islamicate lettered and other high-cultural traditions we find a greater break with the past than in most traditions of everyday life in the region; yet the Irano-Semitic high-cultural traditions, of which the Islamicate formed a continuation, had always been nurtured by the humbler regional traditions of everyday life. But as Islamdom expanded extensively beyond the Nile-to-Oxus region, the cultural break became more total. The everyday culture of the newer Muslim areas had less and less in common with that in the original Irano-Semitic lands. Not only language differed, and many patterns of home life. such as cuisine or house building, but also formative features like agricultural technique, and even much of administrative and legal practice.

What was carried throughout Islamdom, then, was not the whole Irano-Semitic social complex but the Islamicized Irano-Semitic high cultural traditions; what may be called the ‘Perso-Arabic’ traditions, after the two chief languages in which they were carried, at least one of which every man of serious Islamicate culture was expected to use freely. The cosmopolitan unity into which peoples entered in so many regions was maintained independently of the everyday. culture, and on the level of the Perso-Arabic high culture; its standards affected and even increasingly modified the culture of everyday life, but that culture remained essentially Indic or European or southern or northern, according to the region.

Indeed, even between Nile and Oxus local cultural patterns had varied greatly and the Islamicate unity prevailed only limitedly on the local, everyday level. Customary law could be as distant in Arabia itself from the Shari’ah law of the books as in the remotest corner of the hemisphere. Yet the Irano-Semitic core region continued to be distinguishable within the wider Islamdom. There the Islamicate society and its specifically high culture, because of its original relation to local conditions and patterns, had deep local roots as compared to the areas in which the Perso-Arabic tradition meant a sharp break especially with the high culture of the past and had little genetic connection with the everyday levels of culture. We may call this central region the ‘lands of Old Islam’, though the point is not the priority of Islam there but its continuity with earlier traditions; Islam in the Maghrib was almost as old as between Nile and Oxus, yet the Islamicate culture was not much founded in the Latin culture which had preceded it there and the Maghrib cannot be regarded as part of its core area. Throughout the Middle Periods, the lands from Nile to Oxus maintained a cultural primacy in Islamdom which was generally recognized. Muslims from more outlying areas were proud to have studied there and, above all, emigrants from those lands, men whose mother tongue was at least a dialect of Persian or Arabic, had high prestige elsewhere. The social patterns and cultural initiatives of the core area were accorded a certain eminence even when not followed.

The Middle Periods, then, which pre-eminently represent Islamicate culture to us, suffered two pervasive cultural limitations: despite considerable prosperity, their high culture was repeatedly threatened with a reduction of economic and social investment toward minimal agrarianate levels; and in the increasingly wider areas of Islamdom outside the region from Nile to Oxus, the Islamicate high culture was always tinged with alienness. These facts pose underlying problems, which may not be the most important historical problems for the student of the Middle Periods, but which are never quite to be escaped. Why should such weaknesses have appeared in the civilization at all? But then why, despite them, the tremendous cultural vigour, power, and expansiveness of Islam and the Islamicate civilization throughout these periods, when in the name of Islam a richly creative culture spread across the whole Eastern Hemisphere?

![]()

I

The Formation of the International Political Order, 945–1118

The Earlier Middle Period faced problems of totally reconstructing political life in Islamdom. The time saw great political inventiveness, making use, in state building, of a variety of elements of Muslim idealism. The results proved sound in some cases, but provided no common political pattern for the Islamicate society as a whole; but that society nonetheless retained its unity. This was provided rather by the working out of political patterns on relatively local levels, both military and social, which tied the world of Islamdom together regardless of particular states. The Jamâ‘î-Sunnî caliphate assumed a new role as a symbolic rallying point for all the local units. The resulting political order turned out to have remarkable toughness and resiliency and expansive power.

Development of political and cultural multiplicity

From the point of view of what had preceded, the political developments of the tenth century can be looked at as the disintegration of the caliphal empire. Where opposition Shî‘î movements did not gain a province outright, the provincial governors became autonomous and founded hereditary dynasties, or local...