![]()

ONE

The Mehinaku and the Sexual Data

In ancient times, the Sun created man and woman…. He created the tribes of humankind. And to each he gave a place and a way to live.

—from a Mehinaku myth

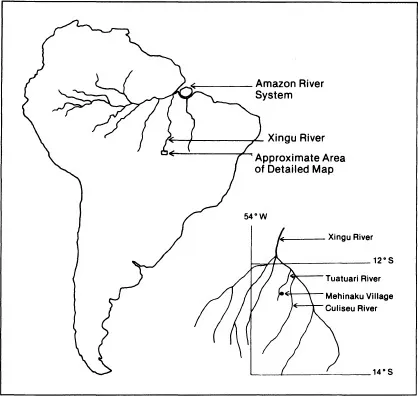

In 1887, the German explorer Karl von den Steinen set out with a pack train of oxen and mules to explore the headwaters of the Xingu River. After crossing nearly 350 miles of arid plains and scrub forest, he reached the vast and well-watered basin of the Xingu and its tributaries. Leaving the pack animals behind and hiring Indian guides and boatmen, he made his way down the Culiseu River. On 12 October 1887, he became the first recorded visitor to a Mehinaku village.

To von den Steinen, the villagers were savages. He cowed them into submission with shouts, gestures, and on one occasion, by shooting a bullet into a housepost (1940,136-7). To the Mehinaku, von den Steinen was an apparition, a spirit visitor from another world who, like all spirits, was malevolent and unpredictable. Eighty years later, the villagers described their ancestors’ reactions to this first visit: “When the white man came, everyone was very frightened and fled to the forest, leaving only the best bowmen in the village…. the young girls covered their bodies with ashes so they would be so unattractive that they would not be carried off. The people were given knives by the visitor but did not understand them, and they cut their arms and legs just trying to see what these new things were for.” Today, the Mehinaku are easier to reach and more accustomed to visitors. They live on a vast government-secured reservation, the Xingu National Park (see map), whose headquarters are linked to the Brazilian Indian Agency in São Paulo by daily shortwave transmission. Yet the culture of the tribes of the region remains surprisingly similar to what von den Steinen described. The visitor still senses that he has left a familiar world and stepped into a distant time and place.

Location of the Xingu National Park and the Mehinaku Village.

My wife and I first arrived in the Mehinaku village in 1967 when I was a graduate student of anthropology. We had begun our trip from Rio de Janeiro on a government plane, an ancient C-47 that had been used in World War II for paratroop missions. We sat with the other passengers on the long narrow metal benches on either side of the plane; the central aisle was reserved for cargo bound for airforce outposts—huge sacks of rice and beans, carcasses of beef—and for injured or sick persons on stretchers being carried to distant hospitals. In Xavantina, an all-but-inaccessible village on the “River of the Dead,” we were stranded for five days awaiting a spare part that had to be flown in by the next plane from São Paulo. On the last leg of our flight, we flew over nearly two hundred miles of uninhabited forest and plain to land at Posto Leonardo Villas Boas, the headquarters of the Xingu National Park Indian reservation.

The post looked much as it does today: a few small buildings, a dirt air strip, and a canoe port on the Tuatuari River. Visitors were provided with a breakfast of sweet coffee and milk, two meals of rice and beans, and a space to hang their hammocks under a large thatchroofed verandah. It was there that we first met the tribesmen of the region, who came to take a close look at the Americans and their bags of supplies and gifts. Among the visitors were the Mehinaku, who arrived in several canoes in the hope of bringing us back to their village. “We Mehinaku dance a lot,” volunteered one of the young men who had an inkling of our interests. “We sing a lot too. And we speak a lot of Portuguese.” The Mehinaku also claimed that their village was free from biting insects and near a beautiful stream. These were strong selling points, and so the following day, we set out for the Mehinaku village. The trip from the post was three hours by canoe along the Tuatuari River, and then a little more than an hour over land. The women carried our heaviest gear on their heads, while the chief walked alongside us, shouldering only my prestigious rifle.

Arriving at the community, the chief escorted us to his family’s house. Our hammocks were tied to the house poles while children raced about to bring us firewood and water. One of the women presented us with manioc bread covered with a thick, spicy fish stew. Little boys tied and untied our shoe laces, stared unbelievingly through my eyeglasses, and peered into my mouth to marvel at my gold fillings. Later in the evening, the men of the village carried small benches sculpted in the shape of birds out to the center of the circular plaza, where a small fire was burning. The chief, who had assumed the role of my host, brought me with him. After being presented with a long cigar, I was asked a series of questions about why I had come and how long I intended to stay. I was closely interrogated about my relatives. Were my mother and father living? Was my sister married? Why did I have no children? What of my uncles and aunts?

As a beginning anthropologist, I understood that among the Mehinaku, a tribal community of only eighty-five persons, kinship was the basis of social life. The villagers’ inquiry was an effort to bridge the cultural gulf between themselves and the strange outsiders. But I was not prepared for the next line of questions, which were initiated by the chief. “We have heard of Americans,” he assured me. “They are white men like Brazilians, though they are taller than Brazilians and other white men. Is it true that Americans eat babies?” I told him that was not true, and that Americans would be as horrified as Mehinaku at such a practice. The chief was apparently willing to accept my reassurances, yet the possibility of Americans’ eating babies was within the realm of belief. I had entered a world astonishingly different from my own, so remote and parochial that my humanity was open to question. Yet in the days and months ahead, I came to appreciate that the Mehinaku world seemed isolated and remote only from my own perspective.

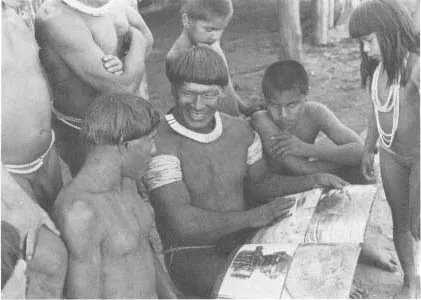

Fig. 1. The world beyond the village. Our interest in the Mehinaku is matched by their curiosity about us. A book of photographs will circulate from house to house, and the visitor is closely questioned about the meaning of each picture. Where do the people who are illustrated live? How long would it take to get there? Are they warlike? Are they related to the visitor and his tribe? Do they make machines or buy them from Brazilians?

The villagers and the eight other similar tribes of the region had lived for hundreds of years in the vastness of the Upper Xingu Basin where they created a rich and complex culture. They surmounted the barriers of their different languages and developed a peaceful system of trade, intermarriage, and participation in each others’ ceremonies. Today the invitations to these rituals are issued by ceremonial ambassadors who exchange gifts with the men of the neighboring tribes and address them with long speeches in an archaic tongue.

All of the tribes who participate in this system are called putaka by the Mehinaku, a term linguistically linked to the word for village and connoting a civilized and hospitable way of life. The term for “guest,” by which I was referred to, is also putaka. In reality, however, my status as a putaka was at best honorary. Like all other white and Brazilian visitors, I was a kajaiba, a term that is tinged with ambivalent emotions of respect, fear, and uncertainty, even though the kajaiba, are regarded as humans (neunei). Both races were made in ancient times by the Sun, who sat the tribal chiefs about a fire in the center of his village. He then passed gifts around the circle, presenting to the kajaiba milk, machines, cars, and planes, and to the Xinguanos, manioc, bows and arrows, and clay bowls. Despite their different life ways, putaka and kajaiba are children of the Sun. Not so the non-Xingu Indians surrounding the putaka tribes, who in the past have raided the area, kidnapping women and children. These Indians are called wajaiyu, a term that is seldom uttered without a tone of contempt for their reputed filth and barbarism. Unlike the peaceful, civilized putaka, the wajaiyu “kill you in the forest. They sit on the prows of their canoes and defecate into the water. They eat frogs and snakes and mice. They rub their bodies with pig fat and sleep on the ground.”

Gradually, as I came to appreciate the complex world the Xinguanos had created, I began to see the Mehinaku village, not as remote, but as a center of life. Each morning I was awakened by the rhythmic whistling of the young men as they went to bathe and the bustle of activity as the villagers left to tend their gardens or go fishing. Later, the women returned, carrying baskets of manioc tubers to begin the long process of reducing them to flour. At all times, the children played about the village. They played “plaza games,” in which they imitated the men’s wrestling in front of the men’s house. By the river, they sculpted turtles, alligators, and forest animals from clay ánd ambushed one another in games of “jaguar.”

Toward afternoon, the men returned from fishing trips, and the villagers whooped as they came into view along the straight paths that radiated from the village. Later in the men’s house, after the heat of the midday sun had begun to subside, the fishermen worked on crafts and decorated their bodies in preparation for “wrestling time.” Close by the wrestling matches, several of the men, dressed in feather headdresses and fiber skirts, danced and sang for the spirit Kaiyapa, who must be periodically appeased to ward off illness. After “wrestling time” families took their meals together. The returning fishermen shared their catch, so that there was something to eat in every house. As the sky darkened, the women and children got into their hammocks, and the men gathered around the small fire in the center of the village. Behind them was the wall of houses that surrounded the plaza, then the dark rampart of forest that encircled the now quiet village; overhead, a dome of stars, brilliant beyond the experience of city dwellers. Only during those quiet moments, when the hum and bustle of human activities had subsided, did my feeling of remoteness and isolation return.

The Nature of the Sexual Data

I had not intended to study sexuality when I first began to work with the Mehinaku. After my first field trip, however, I became convinced that a full understanding of the culture demanded it. Community organization, religion, the division of labor, and even the village ground plan reflected the importance of sex and gender. The villagers themselves seemed to have drawn the same conclusions. Their explanations of the conduct of their fellows emphasized erotic motivation and the idealized images of masculinity and femininity. But the Mehinaku did not clearly formulate a philosophy of gender and sex. A question such as “What does it mean to be a man or a woman?” inspired incomprehension in my informants. To approach the topic as an ethnographer, I found that I needed what has been called a “sociology of the obvious” in order to discern the assumptions and logic that the villagers took for granted. The data that inform this book therefore come from a variety of sources that include but go beyond the Mehinaku’s own formulations about their society. Much of this material is the basic data of social anthropology, including ritual, kinship practices, dress, concepts of development, and the life cycle. Some of the evidence, however, is more personal in nature and requires a special introduction.

MEHINAKU SEXUAL BEHAVIOR AND ATTITUDES

Like many of the Indians of the Upper Xingu, the Mehinaku are open about sex (cf. Carniero 1958; Zarur 1975). There is little shame about sexual desire, and children will tick off the names of their parents’ many extramarital lovers. Coming from a culture where such topics are approached delicately did not prepare me for the villagers’ candor and unembarrassed accounts of sexual conduct. In retrospect, as I go over my taped interviews and other data on Mehinaku sexuality, I find that some of my uncertainties and gaps in knowledge are due more to my own occasional reticence than to my informants’ unwillingness to respond. My material on female sexuality, for example, seems limited in light of the villagers’ openness about sexual intimacies. Much of my information on this topic was elicited by my wife on our first field trip. This material was later supplemented by my own interviews and by indirect information such as biographies, dreams, and drawings.

My data on male sexual conduct is fuller and more intimate than my information on the women. The best of this material has come from my most recent trips to the Mehinaku (especially during the summer of 1977) because I had already acquired some knowledge of the topic and built relationships of trust and confidence with the villagers. The richest information of this period is included in some fifty hours of recorded interviews with four of the village men, the youngest a boy of twenty years, the oldest, a famous myth teller and village elder in his late sixties, the oldest man in the village. These interviews, conducted in the Mehinaku language, range from biographical information, dreams, and personal experiences to directed discussions of sexual attitudes and conduct. Interspersed throughout the interviews are a remarkable series of sexally oriented myths, which the men frequently offered as illustrations and evidence for their ideas about sexuality. Since these myths form some of the essential data in the study, we need some preparation for their logical structure and significance.

SEXUAL MYTHS

History for the Mehinaku has relatively little depth. Ask a villager about his ancestors, and he quickly moves back through the four or five generations of known genealogy and community history. In the minds of the villagers, this historical time was preceded by a period of time, perhaps equally long, in which events are uncertain and ancestors unknown. No matter how murky this time may have been, however, the life of the Mehinaku then is assumed to have been very much like that of the villagers of today, albeit idealized. Chiefs were said to be less prone to invidious oratory, and virtually everyone was taller, stronger, and better than they are today. Nonetheless, the descriptions of this period are plausible and may be based on fact. Both of these periods of historical time are designated “the past” (ekwimya).

Moving still further back in time, beyond the boundaries of the known or the possible, we come to the distant past, a period designated as ekwimyatipa, which I gloss as “ancient” or “mythic” time. During this period, the Sun shaped the geography of the Xingu and created the culture of its people. Breaking a great cauldron of water along the headwaters of the Xingu Basin, he fashioned the network of interlacing rivers and streams that crisscross the Xinguanos’ territory. Then he shot arrows into the ground, creating the various tribes of humankind, and gave them their speech, dress, rituals, and technology. So rich is the oral tradition describing this period that there are few institutions that do not have a charter from mythic times. Religion, the relationships between the tribes of the region, geography, and cosmology all receive detailed treatment in these origin myths.

Within the body of myths, we find a set of stories that directly probe the nature of masculinity and femininity. These tales are not linguistically differentiated from others, though they occasionally may be jokingly referred to as itsi aunaki, “genital myths,” as opposed to simply aunaki, “myths.” With any encouragement from the listener, some of the stories are told in succession, for they are informally regarded as forming a group (teupa), in contrast to the remainder of the Mehinaku mythic heritage. Moreover, unlike other Mehinaku myths, these sexually related stories are usually told in the men’s house rather than in the residences. The women are aware of the tales and even tell them themselves, but the stories are more properly a part of male culture.

Since the myths are a fundamental source of data for our study, it is critical to understand what they mean to the Mehinaku and what uses we can make of them. Clearly few, if any, of the stories can be read as literal history. Many of the events they describe are impossible (such as the creation of the Xingu River) or improbable (the belief that Mehinaku society was once matriarchal). The villagers themselves recognize the implausibility of the legends, at least for present times. Question an informant about the truth of the story, and he is likely to say: “In mythic time, mythic time, these things took place—not today.” By the concept of ekwimyatipa, the Mehinaku create a second world where the laws of day-to-day living do not apply. In the curiously frozen world of the mythic past, events may occur out of sequence or be in total contradiction to one another. Thus we learn that the Sun, who created all men, was himself born at a time when men already seemed to exist, and that women, who were created to meet men’s sexual needs, were sculpted out of wood prior to the creation of men. The Mehinaku are not overly preoccupied with such contradictions. They implicitly recognize that the myths are ahistorical and stand apart from the mundane world, where the limitations of reality can be ignored only at one’s peril. As in the world of dreams, mythic events may occur with little relevance to the laws of space or time.

MYTHS AND DREAMS

The similarity of myth and dream, first proposed by Freud and subsequently developed by Jung, Roheim, and others, is perceived by the Mehinaku. As one informant speculatively remarked, “A myth is a dream that many have begun to tell.” For our purposes, the comparison is particularly apt. Both myth and dream are fantasies whose content is minimally constrained by the checks and balances demanded by action in the real world. Thus the myth reveals emotional truths even when the plot is outlandish or impossible. Our search for these truths is facilitated by the special circumstances of the Mehinaku and their mythology. The Mehinaku are a small, homogeneous tribe whose mythology reflects a common heritage and a shared emotional life. Moreover, many Mehinaku tales are unabashedly rooted in the sexual wishes, fears, and conflicts that psychoanalysis tells us are at the core of our innermost selves. The stories are redolent with emotionally loaded sexual themes. Staple fare in Mehinaku mythology is incest, bestiality, and castration.

The style of the myths also encourages us to view them as personal fantasies. The tales often have an eerie, dreamlike quality suffused with elements of the mysterious and the uncanny. Scenes shift without explanation from earth to air and water. Symbols are condensed, so that the protagonist...