![]()

CHRONOLOGY

Chronology prepared by María Guadalupe López Elizalde y Gallegos LL.

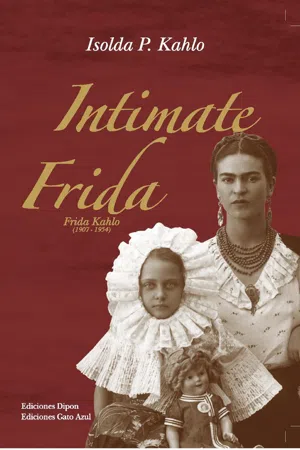

FRIDA KAHLO

•1872. The birth of Guillermo Kahlo occurred during this year (Baden-Baden, 1872—Mexico D. F., 1941), son of Jacob Heinrich Kahlo (a jewelry dealer and salesman of photographic commodities) and Henriette Kaufmann (housewife). They had several children, among them, Wilhelm (Guillermo), María Enriqueta, and Paula.

•1876. The birth of Matilde Calderón y González occured during this year (Oaxaca, 1876—Mexico D.F., 1932). She was the eldest of twelve children. Her parents were Mrs. Isabel González González and Antonio Calderón, photographer of indigenous ancestry, native of Morelia, Michoacán. He lent Guillermo Kahlo his first photographic camera. Matilde persuaded him to continue with his father’s profession.

•1886. The birth of Diego Rivera occurred during this year (Guanajuato, Gto., 1886—Mexico D.F., 1957).

•1891. At the age of nineteen, Guillermo Kahlo traveled to Mexico. He worked as a cashier in the glassware Loeb, as a salesman in a bookstore and later in the The Pearl jewel shop, which belonged to German immigrants who had arrived in Mexico with him. After his arrival he changed his name and family name (Wilhelm Külo).

•1894. Guillermo married a woman whose family name was Cárdena. She died four years later while giving birth to her second daughter. The daughters from Guillermo’s first marriage were María Luisa and Margarita. It was said that “they were both left in a convent, when Guillermo married for the second time.”

•1898. The wedding of Guillermo Kahlo and Matilde Calderón occurred during this year. He was twenty-six and she was twenty-four, according to Hayden Herrera’s biography. Matilde kept in a leather portfolio the letters of a former boyfriend who had committed suicide in her presence. “That man was always alive in her memory,” wrote Frida in her diary.

•1904. Guillermo Kahlo built the “Blue House” of Coyoacán. The property, which he had bought, was a part of the state Del Carmen. It was “a rather small plot of land” (taken from the biography by Hayden Herrera).

•1904-1908. During these years, Guillermo Kahlo compiled more than 900 plates, which he himself prepared. This work was commissioned on his behalf by José Ives Limantour (Secretary of Finances of Porfirio Díaz). The goal of this project was to photograph the whole Architectural Patrimony of the Nation. Guillermo was granted the title of “First official photographer of the National Cultural Patrimony of Mexico.” He also took wonderful pictures of noted politicians, so it is very likely that by the time Frida was born he enjoyed a rather comfortable economic position.

•1907. The birth of Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón in Villa de Coyoacán was on July 6, 1907. Her mother became ill when she was born, so she was fed and raised by a local wet nurse. We knew that the older sisters always helped their mother raise the younger sisters and that Frida and Matilde did not have a good relationship. With time Matilde Calderón started suffering from a condition similar to the one experienced by her husband(epileptic seizures).

•1912. In a letter, Frida talked about the tragic decade and how her mother fed and cured the wounds of some Zapatist rebels.

–During the Revolution, work became scarce. Guillermo and Matilde had to mortgage their house and sell the French furniture that was in the living room. They also rented out a few rooms.

•1913. Frida was six years old and suffered from a poliomyelitis attack. According to her, she subsequently had a brief psychological breakdown and became more attached to her father. He used to say that Frida was the daughter who most closely resembled him.

•1914. Frida was seven years old when she helped her fifteen-year-old sister Matilde escape to Veracruz with her boyfriend. Matilde was born in 1899.

–Diego Rivera was in Madrid with painter María Blanchard.

•1915. Diego lived in France and was ready to enlist in the army.

•1917. Mexico had a new Constitution: “the most advanced the world had ever seen, at least on paper” (The Fabulous Life of Diego Rivera: Bertram D. Wolfe, 1963, p. 91). The birth of Diego and Angelina Beloff’s son occurred during this year.

–The poet José Frías, a friend of Diego until the end of his life, told the painter’s biographer that “he lived in the Montparnasse quarter, Rue du Départ. He had moved there after the birth of his son. It was snowing, and there was no heating system…He never stopped working, even as we spoke. For him, painting was the most serious thing in the world. He had grown increasingly distant from Picasso (as well as the other cubists), after having been his intimate friend.” He was introduced to Alberto Pani.

•1918. This was Europe’s worst winter in many years. Diego’s son died. The great French poet Guillaume Apollinaire, leader of the Surrealists, was wounded by a machine gun burst while he was writing a poem, leaning against a canon. He was later to die of pneumonia.

•1919. Marievna Vorobiek gave birth to a daughter, Marika, whom Diego called “a child of the armistice.” In fact, he acknowledged her as his daughter when, once in Mexico, he left money for the girl with Adam Fischer. He later sent her more money through Elie Faure. Diego kept with him his daughter’s letters.

•1920. Alejandro Gómez Arias, an ex-boyfriend of Frida, said in an interview, “My relationship with Frida started in preparatory school, where we were classmates. She came from the German College, the way she dressed and thought were typical of a German school… She was intellectually very sharp and always stood against the traditional family norms. Frida became closer to our group until she finally joined the ‘Cachuchas.’ As a matter of fact, she became the most interesting figure in the group.” Besides Gómez Arias and Frida, the other members of the “Cachuchas” were José Gómez Robleda, Miguel L. Lira (Chong Lee), Ernestina Marín, Agustín Lira, Carmen Jaimes, Alfonso Villa, Jesús Ríos Ibáñez y Valles (Chuchito), Manuel González Ramírez, and Enrique Morales Pardavé. Alejandro Gómez said, “Frida and I were young lovers and did not have the serious prospects of a formal engagement, such as marriage and all those things.”

•1921. Frida obtained her school certificate from the Oberrealschule in the German College of Mexico.

–In November Diego traveled to Yucatán with José Vasconcelos. He gave Diego one of the walls of the Preparatory School of the University of Mexico to decorate. Diego worked there for a year.

•1922. Frida Kahlo registers in the National Preparatory School. Out of two thousand students, she was one of the thirty-five women to be accepted that year. There she became a member of the group known as “The Cachuchas,” which took its name from the traffickers’ caps used to identify themselves. They supported the social nationalist ideas of the Secretary of Education José Vasconcelos.

–Guillermo Kahlo had his own photographic studio in the “The Pearl” jewelry shop in the streets Madero and Motolinía.

–This was the year of the wedding of Diego Rivera and Lupe Marín (the marriage lasted from 1922 until 1929). The ceremony was celebrated in the church of San Miguel in Guadalajara. The witnesses were María Micher and Xavier Guerrero. There was no civil marriage.

–Toward the end of this year, Diego joined the Communist Party. His membership I.D. number was 992. Diego committed adultery with the younger sister of Guadalupe Marín. She went to Guadalajara until Diego managed to salvage the relationship. A little later, their first daughter was born. Her name was Guadalupe, but they gave her the nickname of “Picos.” Ruth, the second daughter, was lovingly called “Chapo,” a diminutive for chapopote.

•1923. Frida and Alejandro were dating. They wrote to each other. The relationship came to an end in 1928.

–Among the members of the Executive Committee of the First Convention of the Communist Party were Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros and Xavier Guerrero, a painter who was to help Diego with the murals of the Bolívar Auditorium, the National Preparatory School and the frescos of Education and Chapingo. Xavier Guerrero was nicknamed “El Perico,”26 because he never talked. Among the most distinguished members of the syndicate were two women, Nahui Olín (Carmen Mondragón) and Carmen Foncerrada. Roberto Montenegro and Carlos Mérida, a Guatemalan painter, joined in later.

–In March Diego began painting the 124 frescos of the Office of Public Education. During this period he also completed the 30 frescos of the Agriculture School of Chapingo.

–The unveiling of the mural in the National Preparatory School was on March 20. José Vasconcelos received the invitation for the ceremony on an orange piece of paper printed by the Syndicate of Workers, Technicians, Painters, and Sculptors. (They thanked him profusely for having taken care of them after a nearly fatal fall from the platform where they were working.) Vasconcelos gave other walls from the same school to Siqueiros, who had just arrived from Spain, and to Orozco, who had recently participated in a failed invasion of the United States. Part of the commission was also given to Fermín Revueltas and to five other men who had worked as assistants to Rivera. They were Jean Charlote, Fernando Leal, Armando de la Cueva, Ramón Alva de la Canal, and Emilio Amero. Lupe Marín was painted three times on the wall of the Preparatory School. She also posed as a model for the nude paintings of Chapingo and the Office for Public Education. Tina Modotti also appears in the Chapingo frescos. Diego fell again from the platform and was taken to Lupe’s house. In her own words, she could immediately tell that the painter was lying about the seriousness of his injury. She refused to take care of him, because she knew of his affair with Tina.

–On May 13, Frida addressed to Alejandro Gómez Arias a letter signed with the pseudonym “Rebecca.”

–On July 20, the revolutionary Pancho Villa was assassinated on his ranch.

–In August Frida wrote a letter to Miguel N. Lira (Chong Lee), who was then living in Tlaxcala. In this letter she asked him to answer her using the pseudonym “Rebecca” instead of her real name, and to send any messages to the address on Londres Street No. 1.

–On December 19, Frida wrote an amusing letter; she was angry because she “was punished for having hit that stupid little wimp Cristina. (She had taken some of my things.) She cried and screeched for about half an hour. I was then given a good spanking, and they did not let me go to yesterday’s Eastern festivities…” The letter was addressed to Carmen Jaimes, whom she calls “Carmen James.”

•1924. On June 23, Diego signed a new contract with the government (after the Delahuertista Insurrection), so that he could finish the frescos of the Office of Public Education. If Calles were to become the new president, said a journalist, he would order the destruction of the murals. A wave of vandalism targeted Orozco’s murals in the National Preparatory School. When part of the press was attacking Diego’s “monkeys,” some journalists and international critiques started paying attention to the Mexican muralist pictorial movement. Diego painted Vasconcelos as one of the vandals who was opposed to murals as a legitimate form of art.

•1925. On September 15, the accident occured that was to change Frida’s life forever—a tram hit the bus in which she was traveling.

–Diego left the Communist Party.

•1926. Sometime during the summer Diego was readmitted to the Communist Party. He expelled himself from it again in 1929.

•1927. On March 30, Frida wrote a letter to Alicia Gómez Arias, sister of Alejandro, who at that time was in Europe. She apologized for not having invited her to her house: “I beg you not to think poorly of me if I do not invite you to come over to my house, but, in the first place, I do not know what Alejandro would think of this, and also, you can not imagine how horrible this house looks. I would be really embarrassed to have you come to such a place…”

–On April 23, a new letter to Alicia Gómez was addressed. Frida told her that the doctor prescribed the use of a plaster corset instead of subjecting her to a new surgery.

–On May 16, Frida wrote to Miguel L. Lira. She told him she would no longer be able to finish his portrait because her plaster corset had to be replaced. She moved to the home of her sister Matilde. The address she gave him was the one of Dr. Lucio—102-27. She called herself “the Cachucha number 9.”

–On Monday, June 6, the doctors replaced for the third time Frida’s corset. This time it was to remain fixed.

–Guillermo Kahlo opened an independent photographic studio on September 15th Street.

–On July 22, Frida addressed a letter to Alejandro Gómez Arias. Sh...