This is a test

- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

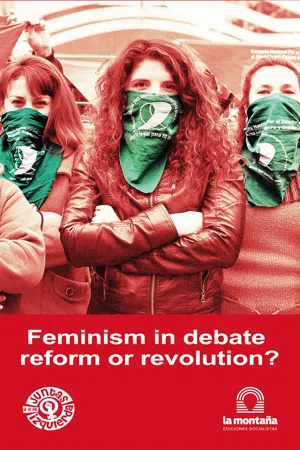

Feminism in debate, reform or revolution?

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In this collective work we return to old controversies that the feminist tide reopens, as well as new and complex questions that reality raises. Among those controversies that are becoming relevant today, we address here the patriarchy-state relationship, the border between the different reformist currents and revolutionary feminism, as well as the construction of the latter. In turn, regarding the new, we include abortion as a right now in dispute, the religious-political fundamentalist crusade, the validity or not of punitivism in the face of male violence; the dilemmas of surrogacy, domestic work, and prostitution or sex work; identity and intersectionality policies and the challenges of the LGBTI + movement.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Feminism in debate, reform or revolution? by Celeste Fierro in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Feminism & Feminist Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter VII

Housework: a debate whit Federici

In the midst of the new global feminist wave, many debates from past decades resurge that address the issue of housework and its relationship to the capitalist system. The polemic began in the 1970s and focused on the theory of social reproduction that was defended, among others, by Marxist feminist researchers such as American Lise Vogel and later Tithi Bhattacharya. This theory shed light on how capitalism uses the reproduction of the labor force, characteristic of housework, to exploit labor in the process of production of commodities.

This position is today the most widespread among left feminist organizations, though not always under the same title, and was criticized by radical feminist authors such as Heidi Hartmann and Shulamith Firestone, who reformulated Karl Marx's theory of production by opposing the concepts of production/reproduction. On one hand, their criticism of Marx focused on the absence of women in his analysis of the reproduction of the workforce, to which he did not assign a particular gender. They also conclude that housework should not be understood solely as reproduction of labor force, but as another form of exploitation.

In her recent book Patriarchy of the Wage, Italian feminist Silvia Federici takes up some central categories of Marxist feminism and its criticism of Marx, reviving a debate that can be synthesized in a few points.

Housework: Is it Productive? Does it Generate Value?

In his pinnacle work, Capital, Marx states that only labor that produces exchange value is considered productive; that is, labor that generates a new value, such as converting wood into a table (commodity), thus adding a new value. But that commodity not only has a use-value (due to its utility) but also an exchange value (because it can be exchanged for different use-values) that will be set by the market.

Exchange value is opposed to use-value due to the simple fact that a commodity cannot be used and exchanged at the same time. The exchange takes the form of an equation (for example, a table equals two pairs of shoes) and does not represent a specific quantity but a quality, a “something in common” that allows them to be equated. That quality, that unit of measure in common, is the labor force used in the production of all commodities.

In summary, the exchange value is not determined by the material properties of this or that object, but by the amount of human labor it contains. The peculiarity of capitalism is that this value is produced in a socially necessary time of work (a collective unit of time), in which the class that owns the means of production, the bourgeoisie, appropriates a part of that value that labor produces: surplus value (value added). Each worker, instead of receiving the money equivalent to the value their work generated, receives only part of it as salary. That is, surplus value is the unpaid labor that the capitalist appropriates and is the source of his profit. That mechanism that Marx discovered was then questioned in the field of housework.

Many Marxist points of view understood housework as oppression and not as capitalist exploitation, because it is not productive. This conclusion was based on Capital´s chapter on “simple work”, which only produces use-value. In that sense, workers sell their labor power in exchange for use-values with which they meet their immediate needs, which, unlike capital needs, are limited: workers only buy what they need to live and their reproduction is based on those needs. Housework was placed at that level: production of use-values for survival.

This vision was criticized for not taking into account the participation of housework in capitalist profits: that is, the mechanisms by which the bourgeoisie benefits from the feminized, unpaid housework that plays a key role in reproducing the labor force that capitalists extract surplus value from today (husband) and in the future (children).

Federici raises several differences with these points. On one hand, she argues that the Marxist definition of productive work has a “masculine” bias: “What Marx did not see is that in the process of original accumulation, not only was the peasantry separated from the land, but a separation also took place between the production process (production for the market, production of goods) and the reproduction process (production of the labor force); these two processes begin to separate physically and, in addition, to be developed by different subjects. The former is mostly male, the latter female; the former remunerated, the latter unpaid.”

According to Federici, Marx gave no importance to women´s role in the reproduction of the labor force and did not think about the specific way in which capitalism benefits from housework. According to her, Marx held that the reproduction of the labor force happens through the acquisition of commodities, while Federici sees it as productive work: “it produces the workers themselves”, the home is “the other factory.” According to her, to considering housework “unproductive” minimizes it in contrast to the labor that produces goods. That is why Federici, as well as the radical feminists of the 1970s, hold that housework is exploitation and not just oppression.

Using Marxist categories, Federici and other feminists86 criticize that Marx omits the productive character of housework and thus reinforces its devaluation. However, it is worth considering whether such devaluation is due to Marx´s ideas or to capitalism itself. According to Polish revolutionary leader Rosa Luxemburg, “all the toil of proletarian women and mothers between the four walls of their homes is considered unproductive. This sounds brutal and insane, but corresponds exactly to the brutality and insanity of our present capitalist economy.”87

In that sense, the devaluation of housework is a direct result of its place in the capitalist system itself, because, in the context of Capital, the terms productive and value do not imply any hierarchical or moral assessment. The fact that a kind of labor does not generate value should not be confused with being considered useless. Moreover, if it were quantified in money as exchange values88, the annual total of female housework amounts to between 20 and 30% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) depending on the country. Even trade and finance, which are vital for the circulation of capital according to Marx himself, do not generate surplus value, therefore they are not considered productive activities, and yet they are much better paid than productive wage labor.

Additionally, in none of her books does Federici give details on what relationship exists between housework and the value generated by the sale of this or that commodity (realization of surplus value), nor on what added value is created by housework. Though she says that it “produces the workers themselves”, it is difficult to observe whether housework adds value to the labor force-commodity or if it simply sustains it. In this regard, two ideas arise. On one hand, it can be argued that the labor force that is sold in the market also has an exchange value depending on whether it is in short or abunda...

Table of contents

- FOREWORD

- Patriarchy and State: From Their Origins to Capitalism

- Feminisms: Liberal, Reformist, Radical...

- Legal Abortion at a Crossroads

- Religious-Political Fundamentalism: The New Crusade

- Against Sexist Violence: Punitivism, Yes or No?

- Surrogacy, a Right or Merchandise?

- Housework: a debate whit Federici

- Prostitution: Abolish, Regulate or Transitional Plan?

- Identity Politics and Intersectionality

- 50 Years Since Stonewall, The Challenges of the LGBTI+ Movement Today

- Building revolutionary feminism

- The right to abortion in the world

- Religions in the world

- General adequancy of laws domestic violence

- Legal status of pregnancysurrogate in the world

- Prostitution situation in the world