This is a test

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In The River, Chris Hammer takes us on a journey through Australia's heartland, following the rivers of the Murray-Darling Basin, recounting his experiences, his impressions, and, above all, stories of the people he meets along the way. It's a journey punctuated with laughter, sadness and reflection. The River looks past the daily news reports and their sterile statistics, revealing the true impact of our rivers' decline on the people who live along their shores, and on the country as a whole. It's a tale that leaves the reader with a lingering sense of nostalgia for an Australia that may be fading away forever.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The River by Chris Hammer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Environmental Conservation & Protection. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

8

TO THE RIVERLAND

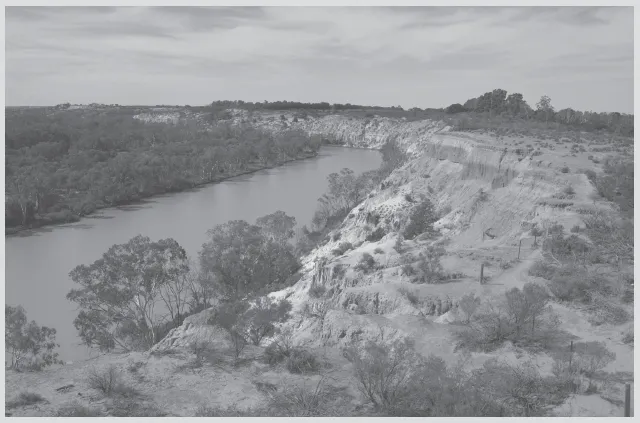

Headings Cliff, on the South Australian Murray, north of Paringa

My father, Kevin, was born in the Victorian bush, at California Gully near Bendigo. My mother, Glenys, was born on the coast, at Malo, where the Snowy River met the sea in the days before it was dammed and diminished. Men, they say, are from Mars and women from Venus, but I know one thing: my dad is from the bush and my mum is from the beach. As a schoolgirl in Melbourne, Mum would spend her weekends sunbaking down at Brighton Beach. Even now, she loves swimming in the sea, staying in for hours, close to the house she finally convinced Dad they should buy on the south coast of New South Wales, near Moruya. Dad likes it well enough, but when he goes for his afternoon walk, he heads off into the bush, not along the beach like everyone else. It’s in their very nature: Mum is intuitive and of the ocean; Dad is practical and of the land. I’m not sure where that leaves me: somewhere in-between I guess. An affinity for rivers is about the best I could have hoped for. I’m a bit like Canberra: an awkward compromise.

My parents met in Murrayville, a portentous name if ever there was one. Mum went there on her first teaching post, assuming it must be on the river. It’s not. It’s in the middle of nowhere, also known as the Victorian Mallee. The Mallee lies in the state’s north-western corner. There’s one sparsely populated swathe running east–west below the Murray, west of Mildura and bordered to the south by the ‘sunset country’ wilderness. Below the sunset country lies another marginal band of farmland, extending from the Murray to the South Australian border. Murrayville lies halfway along this southern band. To the south again lies the Big Desert. The Mallee is home to a tough breed of dry-land farmers, with the emphasis on the dry, who eek out a living in near perpetual drought. Rainfall is about 15 centimetres a year, often less. Only the quality of the soil makes the land viable. Depending on who you ask, the term ‘Mallee Farmer’ is synonymous either with stubborn resilience or with a pathological ability to bet the farm on the next crop. A hundred thousand dollars, maybe two, can be spent sowing a crop on the rumour of rain. It’s not a place for the faint-hearted.

Dad arrived in Murrayville the same year as Mum: 1953, his second year out as a teacher. The town was home to a consolidated school, a then recent innovation that had gathered all the one-teacher schools and used buses to bring in pupils from a wide radius. Dad came equipped with an agricultural science degree. He taught farm science, ran a small farm with his students, and made a few bob on the side fattening a flock of sheep on the school oval. It was a time of postwar confidence; Dad arrived preaching the new religion of technology, DDT and modernity. He advised local farmers on the latest methods and tested their soil for trace elements. He ran agricultural field days, played footy for the local team, and lived out the back of the pub. He made such an impression that when he and Mum decided to leave Murrayville, a wealthy farmer named Heintze tried to hire him to open up farmland on the edge of the Big Desert. With no money of his own, but all the know-how in the world, it must have been a tempting offer. Dad would have loved to have had a crack at farming. But he knew the Mallee could be synonymous with something else: heartbreak. He turned the offer down, much to the relief of my mother.

I drive into Murrayville, ‘Gateway to the Victorian Outback’, on a warm autumn afternoon. There’s been some unseasonable rain, but then any rain in Murrayville is unseasonable. It’s settled the dust but has failed to invigorate the town. It feels not so much gripped by drought as by a pervasive sense of fatigue. Stretched out along the highway, the buildings themselves look tired, the long years having eroded that postwar optimism. They sag, as after a long sigh, their paintwork fading in the sun. An old-fashioned garage, bowsers out in the road, stands with its wooden double doors peeling and propped open. ‘Renown Garage’ reads the sign above the door in lettering once blue but now powdery grey. ‘M bil Service’ it says, the red ‘o’ peeled off and blown away. Further along, a low line of shops stands empty below a rickety awning, the rendering along the roofline crumbled, revealing the erratic brickwork beneath. Up on Reed Street, the main street by default, six stores remain open, huddled together under the corrugated-iron awning of a single-storey terrace row, its facade weathered to pastel and brick. There’s Thurlow’s Newsagency, a Christian bookshop and Nanna’s Milk Bar, with a large ‘For Sale’ sign in the window. The Commonwealth Bank branch, with its wheelchair-access ramp, its aluminium-framed windows and its fluorescent brightness, has been transplanted in its entirety from a fresher, more vibrant Australia. Round the corner, a rusting Austin A30 stands in a vacant lot with a ‘make an offer’ sign propped behind its windscreen. In this climate, the rust is the most impressive thing about it. The grill is missing and so are the hubcaps. Perhaps the same car—shiny, black and brand new—once won an admiring look from my father, arriving in Murrayville as part of a postwar generation of Australians surprised to find themselves contemplating car ownership. The A30 was powered by a straight-four engine displacing 800 centimetres, or four-fifths of a litre (perhaps giving rise to a colourful colloquialism). It could rocket from zero to 60 miles per hour in less than a minute. A real tearaway. I wondered if my parents had ever ridden in this car, this very car now gently falling to bits in the vacant lot, perhaps sneaking off to the movies across the border in Pinaroo. I wouldn’t be surprised; the whole town gives the impression that not so very much has changed since my parents left. Only the pub, the town’s sole two-storey building, is freshly painted and bright. But like the Commonwealth Bank, it’s an illusion created by money from ‘away’, the new veranda and other restorations funded by a government grant. But at least Murrayville is still here. Other towns that existed in my parent’s time, like Danyo, 14 kilometres to the west, have disappeared back into the scrub altogether, with only a highway sign to acknowledge they ever existed.

I drive towards the school where my parents taught, but my imaginings are interrupted by a man standing in the middle of the road, waving his arms frantically. It’s Ken Heintze. At age eleven, he was one of my father’s pupils. He’s been expecting me and must think I’m lost, not something easily accomplished in Murrayville. I abandon my meanderings and pull into the driveway of his neat brick home. Ken is the nephew of the man who once offered to stake my father. He introduces me to his wife, Raelene, and then asks if I want to see the farm. Ken, now sixty-seven and retired, still helps out on the family property most days, driving a tractor for his son or taking a semitrailer through to South Australia. He’s a thin, fit looking man, his grey hair and grey beard resting easy on a lean face under the sort of baseball-style cap favoured by American farmers. Only later does he tell me he’s diabetic and has to keep a close eye on his blood sugar. It’s hard to believe; he displays none of the lassitude of his town.

Maybe it’s the rain that has put a spring in his step; it’s the first decent fall in five months. But the lack of rain before now hasn’t bothered Ken at all. Just the opposite. He says it’s too hot and dry to grow a summer crop in the Mallee, so rain in the hot weather does nothing but germinate weeds, and weeds cost money to control. I smile at the paradox: the worst drought in a century, and here’s a Mallee farmer happy that it hasn’t rained for almost half a year. Now however, rain has come, right on time. It puts a smile on Ken’s face as he casually drives at breakneck speed along dirt roads, one hand flopped atop the steering wheel. We’re at the farm in minutes. Ken and Raelene’s son, Mark, is on the tractor, sowing wheat. Or rather he’s in the tractor. It’s a huge thing. He can’t stop to talk; instead his voice crackles across the u.h.f. radio. I can see him inside the cab, peering out the back window, watching the sowing machine. It’s not a plough, nothing so crude. Rather, the seed is being drilled directly into the soil using compressed air, causing little dust or loss of moisture. Mark’s hands are nowhere near the steering wheel; the tractor is computer controlled, guided by satellites floating in low orbits. The town may have barely changed, but out on the land the technological revolution has continued unabated, rendering medieval the science of my father’s day. For the farmers it’s a constant struggle: forever adopting new technology, forever expanding to achieve economies of scale, forever investing to stay profitable. It’s a struggle Ken fears Mallee farmers are losing.

‘It’s a build up over a long time, since the late 1970s’, he says. ‘Our expenses have started to get level with our income and in many cases gone beyond. You can only last so long by running at a loss. But we know nothing else and this is all we want to do, so we try and do it better. It’s not easy at all.’ Some years ago a prominent politician, a farmer himself, told Ken that entire towns the size of Murrayville were being wiped from the map in the United States. ‘I said we’re not going to let that happen. Or at least we’re not going to let that happen one minute earlier than it has to be. There’s lots of unknowns in life, and not many guarantees. You try and do things to the best of your ability. There’s a lot of stresses on rural people at the moment. And lots of debt. But it’s still a good life. And if I ever had to leave this place it would be very difficult, because of all the people I know and like.’ After a lifetime of aridity, it’s not drought or climate change that worries Ken; it’s the decreasing margin between costs and returns.

We jump out of the truck to clear some old barbed-wire fencing that has somehow been dragged onto the paddock. We’re on a slight rise and it gives me a chance to take in the landscape. The Mallee isn’t flat, not the true flatness of Wakool and the Riverina. It’s not exactly hilly, but there is a rise and fall. It’s a land of whispered promise, a land that needs nothing except rain. It must be something to behold, that one year every decade or two when the heavens really open, and the monotonous tans and shallow creams are illuminated with green. A river wouldn’t go astray either, but they’ve never had one here so I guess they don’t know what they’re missing. We take the barbed wire over to a farm dump, near the scant ruins of a farmhouse, a relic from when the land was settled. The Mallee was largely populated by soldier settlers after World War I. Perhaps after the mud of Flanders, the Mallee looked appealing. The diggers were given 680 acres of land— 1 square mile. And dig they did, undertaking the brutal work of hand clearing the land of the deep-rooted Mallee scrub. But 1 square mile was never going to be enough. They fought on in isolated poverty, surviving on mutton and flour, as the unforgiving land blasted their bodies, tormented their minds, and sniped at their souls. The only way to survive was to buy more land, so neighbour preyed on neighbour in a grim Darwinian dance. By the outbreak of the next war, barely twenty years later, some 60 per cent of soldier settlers in Victoria had walked off their land; the attrition rate in the Mallee must have been among the highest. But it meant that those who survived were the best of them: the shrewdest, the hardest working, the luckiest. Ken Heintze’s grandfather settled near Murrayville in 1924 and prospered, and so did his sons and their sons.

Now a new threat has emerged. Or rather, a new temptation. Murrayville’s hidden strength has always been that it sits above an aquifer of pure water, water that stretches off westward across the South Australian border. It’s why the town was founded far from a river, and why it has endured. Even in the worst drought, there’s been water for stock and for people, water for the town. Now the irrigators have come, refugees from parsimonious rivers, frugal canals and shrinking allocations, alert to the main chance, bringing their massive centre-pivot irrigators with them—huge spider webs of steel 100 metres or more across that revolve on motorised wheels round a central pump site. Ken Heintze doesn’t like them.

‘The beginning of irrigation in the Mallee was about ten years ago’, he says. ‘It’s grown to a point now where it is very prevalent. They’re growing potatoes, mainly. There’s lots of centre-point irrigators pumping huge amounts of water. And as a dry-land farmer I wonder whether it’s sustainable. What if it’s not? Or if it reduces the quality of the water? That could have disastrous effects. We rely on underground water … If the quality of the water deteriorated so it was undrinkable or couldn’t grow anything, like vegetables, that would be drastic. The irrigators could possibly move on, but for those of us who live here, it could spell a catastrophe.’

Ken’s comments cause me to once again revisit the concept of a river. I’ve long abandoned the Oxford definition: ‘Copious stream of water flowing in channel to sea …’ The river has expanded in my mind, encompassing first the flood plain and later the entire catchment, so that it has become the culmination of water in the landscape, not something separate from it. But if my understanding of the river has stretched from one dimension to two, from a line through the landscape to the landscape itself, then why not to three? Water flows not just across the top of the land, but through it as well. A full river channel will push water out into the subsoil; its pressure will resist the inflow of underground aquifers. It’s a matter of balance: if the level in the river channel is low, an aquifer may spill into the river, carrying salt with it. But if the aquifer itself is depleted, then the river may leach away into the soil. And if water is taken from deep underground, does this mean the water in higher aquifers will flow deeper, depriving some other place hundreds of kilometres away of its water? The new basin-wide plan, to be unveiled in 2011, will not just put a new cap on diversions of surface water, but will for the first time include limits on ground water. It’s a move in the right direction, but I can’t say I’m filled with optimism. If governments haven’t been able to properly manage water above ground, if they’ve overallocated what they can see and touch and measure, how are they going to manage the mysterious underground flows? You may not know if you’re tapping last summer’s rain or a downpour from a million years ago. Deplete the aquifers and the blotting-paper catchments may become even more porous.

Later, Ken and Raelene and I go down to the pub for dinner. The first fire of the year is burning in the grate of the front bar, and there is nothing faded in the old hotel’s character. The walls have been painted a deep red and the architraves a jolting green, yet the floorboards are stained a satisfying brown and the bar is well weathered and original. Various denominations of money hang from the 15-foot ceiling, ingeniously launched from the floor below, evidence that revelry remains a possibility. But there’s little of the self-conscious clutter of tourist hotels; instead there’s a kind of appealing minimalism. Photos of the local footy team adorn the walls, together with pictures of a local girl who grew up to be an Olympic basketballer. My father lived at the back of this pub during his time at Murrayville, among a colourful troop that included a couple of alcoholic road workers, a Gipsy Moth pilot known as ‘the Black Prince’, and a hunchback. I wish he were with me now. I’d like to have a beer with him and listen to stories of Murrayville as it was, back before global warming, the global financial crisis, and globalisation. Back when everything seemed more possible.

Mum, of course, could not live at the pub. She couldn’t even enter its front bar, and was too respectable to be seen in the ladies lounge. Drinking in the 1950s was a neatly compartmentalised affair. Men and women were separated, races divided. And there was another divide as well. In Murrayville, as in many towns, there was a wine saloon next to the pub. The saloon sold cheap port and vicious spirits to the drifters and ex-servicemen who floated through the bush, mocking the postwar prosperity. Dad never once entered the wine saloon. He was no snob, but he was a schoolteacher, a respectable member of the community. For him to drink in the saloon would have been as scandalous as Mum sinking pots in the front bar.

Mum lived in a hostel for woman teachers. One of her old colleagues, Ena Lackman, joins us for dinner at the pub. She was the home economics teacher when Mum and Dad were there. Home economics; a title from another era. Ena tells me she came to Murrayville intending to stay for six months, but married a farmer instead and never left, even after he died. I look at her across the table, nattily dressed and smiling, a pleasant face under tight grey hair. It could easily have been my mother sitting there, if things had been different.

Ken tells me he still thinks there’s a future in the Mallee, that every year for fifty years, drought or no drought, his family have been able to coax a crop from the reluctant soil. It’s often not much of a crop, but a crop all the same. He says not many regions, including the much-vaunted Wimmera, could boast such a thing. No doubt he’s gilding the lily, but he has a point. The irrigators have always had it laid on, cheap water on demand. By contrast, the Mallee farmers have been case-hardened, tempered through the decades by the hot Australian sun. They’ve adapted to the unforgiving climate, the vagaries of global markets, the relentless pressure to modernise. The survival of the fittest. But climate change projections place the Mallee right at the epicentre of the great dry predicted for south-eastern Australia. From little rain to practically nothing. Some things you can’t adapt to. I consider its prospects, and Murrayville grows a little more tired and fades a little further into the past.

It’s mid-April and I’m on my last venture along the rivers. I’ve fired up the old Hyundai and it’s carried me out from Canberra once more, taking me towards South Australia and the end of the Murray, to where the river is most diminished and its health most parlous. A journey to the end of a metaphor. The road has greeted me like an old friend, taking me out through Yass to the Hume Highway. The sun has been warm, but slants lower across the sky, setting the countryside in glowing relief. The vines at Murrumbateman, just outside of Canberra, were turning yellow and russet as I drove through, the harvest completed for another year, smoke drifting from a fire in the corner of a field. The countryside had looked tired and dry after the long summer, but not noticeably worse than any other year. There’s been significant rain up in northern New South Wales and Queensland. Bourke copped 20 centimetres in one day in February, flooding the town with water and irony. Further to the north and west, an immense tide is washing through the channel country towards Lake Eyre. There’s talk the drought may be breaking in the north. Which only serves to accentuate the pain in the south.

Little water has reached Menindee, the stopcock between north and south. The lakes have risen from 7 to 15 per cent capacity. And that’s the best of it; across the Southern Basin, the drought has deepened. Rain has fallen here and there, but the rivers and their feeder dams aren’t getting any of it. Inflows into Dartmouth and Hume have fallen to their lowest levels on record for the first three months of the year, lower even than the disastrous lows of two years ago. The remaining water in Dartmouth is so jealously guarded that not enough is being released to flush the river: blue-green algal blooms are being reported along the several hundred kilometres between Albury and Swan Hill. The new Murray-Darling Basin Authority has declared that the drought’s persistence and severity is unprecedented. The ACT Government has unveiled plans to extract 20 billion litres of water annually from the Murrumbidgee to bolster Canberra’s water supply; the announcement has elicited none of the protest ignited by a similar scheme to siphon the Goulburn River to supplement Melbourne’s reservoirs.

Autumn is halfway t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Dedication

- Contents

- Prologue

- Headwaters

- Bourke

- The Last Wild River

- An Ancient Land

- The Inland Sea

- The Forest

- Wakool

- To the Riverland

- Journey’s End

- Epilogue

- References

- Acknowledgements

- Copyright