![]()

ONE

The Finger: A Few Pointers

He has ears, and two eyes, and ten fingers,

Leastways if you reckon two thumbs;

Long ago he was one of the singers,

But now he is one of the dumbs.

—from Edward Lear, “How Pleasant to Know Mr. Lear!” 1879

In Middlemarch, George Eliot bequeathed to future generations the sobering example of the Reverend Mr. Casaubon, that “great bladder for dried peas to rattle in!” as Mrs. Cadwallader so memorably described him—a warning, in other words, against too ambitious or arid a scholarly enterprise, and too hopeless a quest for comprehensiveness. So while using my own fingers to write this book, I have from time to time experienced a sinking feeling that it might too closely resemble an absurd Key to All Mythologies. In those gloomy moments, I have paused for a cup of tea and tried to focus instead on the beautiful, and in our culture fortunately still flourishing, seventeenth- and eighteenth-century ideal of the essay, which, at least in its French derivation, means nothing more than “a try,” a stab at it, a particular view at a given moment, a series of reflections that, by cutting deeply enough into (in this case) one narrow seam of human anatomy and experience, may with luck provide access to rather more.

So while this book contains a lot of information that may be useful for future inquirers about fingers and finger lore, I hope that it will give at least some pleasure and food for thought to nonspecialist readers in what we have conveniently come to know as the digital age. Nevertheless, the handbook portion of my title is a genuine aspiration, and it may be of some comfort to the reader in search of specific technical, historical, cultural, or other folkloric references that while, for obvious reasons, The Finger: A Handbook shuns footnotes, I have instead attempted to provide as much documentation as possible in the endnotes.

My last book, A Brief History of the Smile, began its life as a lecture at a conference of dentists. The Finger: A Handbook owes its existence to a similar collision between the world of art museums (in which I have made my career) and the medical profession. In 1998, a group of orthopedic surgeons in Adelaide, South Australia, led by Dr. Michael Hayes, invited me to give a talk at a conference about hand injuries. For this group, whose interests and activities were far more varied than those of the dentists, I proposed a talk about a particular gesture of the right hand, a pointing gesture. It is common enough, the index finger extended; the middle, ring, and little fingers folded onto the palm; and while the thumb is not necessarily held in along the side of the folded middle finger, or against the outer edge of the index finger, nor is it generally extended as far as possible, as in a child’s worrying approximation of a loaded pistol. The specific, ancient Roman meaning of this more disciplined pointing gesture has today been largely forgotten, yet it crops up in many places.

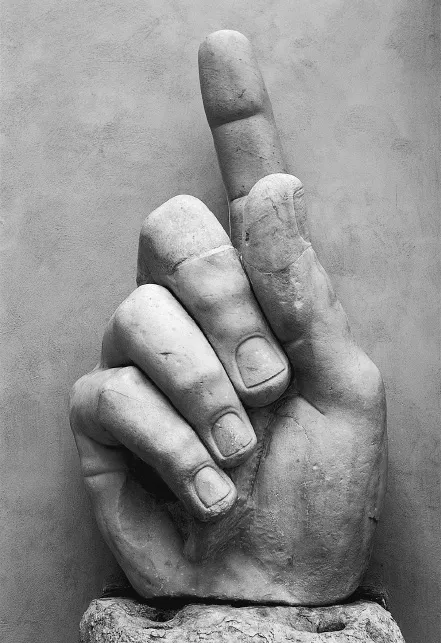

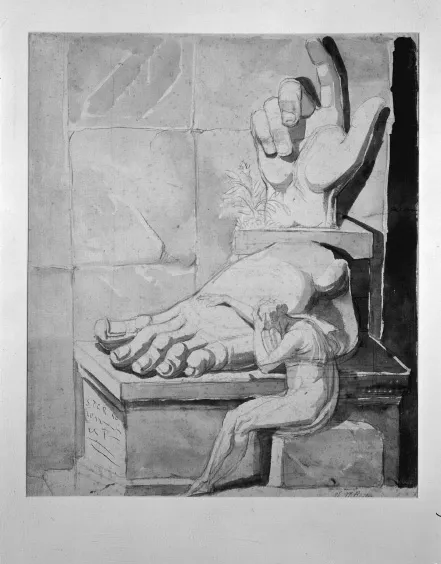

In the courtyard of the Palazzo dei Conservatori in Rome, one may still see a disembodied right hand of this type, one of a number of fragments of a colossal marble statue of Emperor Constantine the Great (324–37 C.E.). In its present position, the enormous index finger points straight up. The expatriate Swiss artist Henry Fuseli was so moved by the scale of these pieces of marble—and the imagined magnificence of the vanished statue to which they once belonged—that he drew himself dwarfed by the stone hand, cradling his head in his own, the left. He called the drawing The Artist Moved to Despair by the Grandeur of Antique Fragments. This was in the years 1778–80, and Fuseli’s fantasy self-portrait drawing has since become a popular and enduring symbol of European Romanticism. The most famous intact example of this ancient Roman gesture is that of the emperor Augustus, whose Prima Porta statue was one of the greatest archaeological discoveries of the nineteenth century (1863) and is now in the Braccio Nuovo of the Vatican Museums. His arm raised, Augustus makes the very same pointing gesture with his right hand.

Much fortified by its usefulness in Roman rhetoric and “oratorical delivery,” the index finger, in this case that of Constantine the Great, was also a potent emblem of military command.

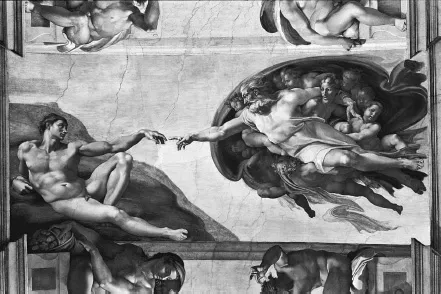

Close by, on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel (1508–12), Michelangelo Buonarroti brilliantly represented the account in Genesis of the creation of man by means of two proximate gestures of the hand. The ingenious sense of drama with which the artist prevented the fingers of those two powerful hands from touching—the hand of God the Father with the pointing index finger, and the awakening hand of Adam, his left—gives the image its emotional charge. No wonder many people read the tiny intervening space as filled with energy, traversed by a powerful aesthetic “zap.” The junction of these two magnificent hands, the one brimming with energy, the other with incipient life, is endlessly reproduced as a detail—these days in advertisements for electrical goods or financial services.We tend to see it as magical, animating, supremely eloquent. But there is good evidence to suggest that the gesture with which God the Father summons Adam into being is not magical so much as military, at the very least commanding in flavor, specifically a gesture of command generally associated with Roman emperors such as Augustus and Constantine, and generals upon whom imperial authority devolved in the field. Its meaning was well understood. Supported by angels, God commands man into corporeal existence: “Be!”

Though “moved to despair by the grandeur of antique fragments,” Henry Fuseli evidently felt free to modify the disposition of the colossal digits, and relax them.

The Prima Porta statue of the emperor Augustus provides a useful model for how the fragmentary hand of Constantine may have been joined to the original statue. The gesture is, of course, the same.

As a set piece of pictorial drama, Michelangelo’s depiction of the creation of man on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel turns upon the fulcrum of the converging index fingers of Adam and God.

Comparatively few of us employ our fingers as instruments of command, but everyone uses them to indicate. Indeed, for the infant pointing is an indispensable tool for the miraculous acquisition of language itself. But the fundamental act of pointing at people and things is only the beginning. Our fingers ultimately follow in gesture many syntactical trajectories. In his great 1632 group portrait of doctors observing an anatomical dissection, The Anatomy of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (1632), Rembrandt chose as the focus of the composition the moment when Dr. Tulp takes up with his forceps certain tendons of the cadaver’s forearm. Those tendons were (correctly) thought to help produce the opposition of the thumb and index finger—that single most important physical asset that has made it possible for us to ascend to our present position at the top of the evolutionary tree. It is rare to find a work of art that pays such tribute to the exact motor functions of the index finger and thumb, though, of course, it is precisely those that painters rely on, and rely on completely, when they tackle the complicated task of picture making. Rembrandt further emphasized the specific meaning of the subject, because with his own free left hand Dr. Tulp offers a vivid demonstration of the physical mechanism of the same tendons he holds with the forceps in his right.

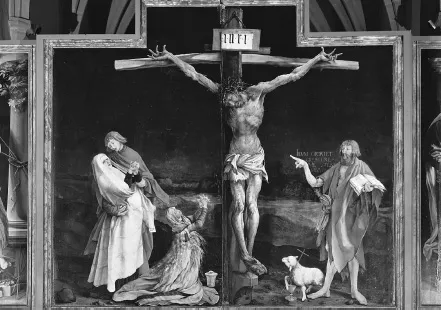

Unlike Rembrandt, most artists have been content to exploit the full range of gestures of which our hands and fingers are capable, to which generations of observers have willingly attached an enormous range of meanings over the centuries. One thinks of the German Renaissance Isenheim Altarpiece by Matthias Grünewald, that terrifying portrayal of the crucifixion of Jesus Christ in which an out-of-time St. John the Baptist, that powerful presence in the opening verses of the Gospel of John, “bears witness” to the light by pointing at Jesus’ dying body with the elongated, outstretched, tautly upward-sloping, tapering index finger of his right hand.

Indication, suffering, supplication, and despair: in his Isenheim Altarpiece, Matthias Grünewald exploited to the fullest extent the expressive and narrative potential of the fingers.

John’s gesture is as controlled as the carefully articulated fingers of the expiring Christ, extending from mutilated palms at the summit of the altarpiece, writhe and curl and twitch in agony. In doing so, they carry for Grünewald a considerable part of the heavy burden of the baffling, mystical narrative of the cross: the instrument of torture, the tree of life. To the left, John, the beloved disciple, supports the Virgin Mary, his slender fingers trained gingerly around her waist, while St. Mary Magdalene, kneeling at the foot of the cross, raises her clasped hands, the fingers tightly intertwined but straight, stiffened by hot grief and dismay, a fervent gesture that contrasts sharply with the folded hands of Jesus’ fainting mother.

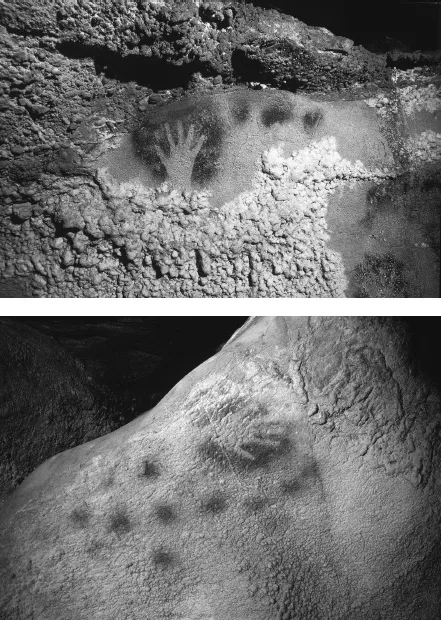

Some of the earliest of all surviving man-made images are of fingers—the silhouettes of disembodied hands with spreading fingers that adorn the walls of caves and other rock shelters in Spain and France and China and Australia. The artist simply placed his hand against the rock, fingers splayed, then took a mouthful of paint, and blew a fine spray over the back of the hand and the immediately surrounding rock surface.When the hand was lifted off, a ghostly “negative” image remained—the earliest form of printing. Primitive man knew perfectly well that the image he produced by this method was far more durable and accurate than the poorer substitute produced by dipping the hand in paint and applying a handprint. Thin coatings of paint, sprayed from the mouth, adhere better and last longer than thicker ones applied under pressure, which tend to crack and peel off.

In a surprisingly large number of examples there are parts of fingers missing or distinctly shortened, possibly the grisly evidence of Ice Age frostbite, or else some form of prehistoric ritual mutilation, scarification, or punishment. In some places there are dozens of these spectral hands and fingers; elsewhere only one has survived. It has occasionally been suggested that prehistoric hand images in caves and rock shelters that apparently lack one or two of the outermost finger joints or, at times, whole fingers, are in fact the result of folding under the relevant digit and spraying over the hand configured so as to deploy one of a range of carefully differentiated signs with particular meaning. While it may never be possible to rule out this possibility, the available photographic evidence suggests that this is unlikely to be true.

These hand silhouettes in the Grotte de Pech Merle at Cabrerets (Lot) in France were made between 15,000 and 14,000 years before the Common Era; similar images survive in caves and rock shelters elsewhere in France, as well as in Spain, China, and Australia.

It is not physically possible to fold double only the terminal bone or “phalanx” of any finger. This would be necessary to produce those images in which only that phalanx is missing. When a film of paint is sprayed over an object of relatively consistent depth that is placed flat against a supporting surface, any variation in depth such as one might expect to observe in a hand placed flat against a stone but with one finger (or more) folded under will tend to produce in the resulting silhouette a corresponding variation in the consistency of line. By the technique of spraying paint from the mouth, the outline of a folded finger ought to be fuzzier and less distinct than the crisper outline of its outstretched neighbors. As far as I can tell, this is not generally the case. Prehistoric hand and finger silhouettes are remarkably even in outline. Either they genuinely preserve the profile of a hand with partly missing digits, or the image was tampered with or “corrected” after the initial spraying so as to adjust the outline for clarity.

Why are these mysterious prehistoric relics so moving? It is not merely their extreme antiquity. It is also, I think, the fact that they correspond so exactly with what most of us now observe projecting fussily from the end of each arm—every day, all day long, the only parts of our bodies, moreover, that we see (without the aid of mirrors) routinely uncovered, acceptably naked. Today we might expect to create an almost identical imprint with our own hands were we to follow those simple steps, and indeed, until recently some Australian Aborigines still added their handprint to that chorus of ancestors with whom they cherish an unbroken connection. This is humbling.

That constant visual engagement with our own hands and fingers, often at extremely close range, can have unexpected consequences. Beginning in 1958, the British Broadcasting Corporation aired a series of television programs entitled Your Life in Their Hands, which was all about surgery. This was not for the fainthearted, because a number of these presented whole operations, benefiting from what was still in Australia the relatively recent introduction of color television, in graphic close-up. As a schoolboy, I remember being fascinated and far from repelled by most episodes. There was mostly an abstract quality to that tightly circumscribed rectangle of sanitized operating-theater green cotton which placed at one remove the untidy jumble of shiny pink organs wobbling inside the tummy or chest cavity. One saw the surgeon forthrightly thrusting his gloved hands inside, rummaging for arteries, extracting tumors, then sewing the whole thing up with a needle and thread. There was in this spectacle a detached quality that for the layman made it not merely tolerable, but at times engrossing too.

Only one of these programs, I recall, induced a certain clamminess in the palms of the hands and sharp intakes of breath, and eventually caused me to change channels. This dealt with an operation on the tendons of somebody’s hand. There is something particularly desperate about seeing the surgeon’s scalpel gain entry to a part of the body that is as constantly before one’s eyes as a thumb or finger. In that sense only, it is impossible to place at arm’s length. Which makes you wince more readily, the thought of hitting the top of your head on a low beam, developing acute appendicitis, or by accident getting your finger jammed in a door? “Men’s natures wrangle with inferior things, / Though great...