![]()

1

‘Back to the basics’

Elections and enterprise bargaining, 1989–93

Towards the end of 1988, Harry Quinn went off for health problems so I then was the acting secretary. During that period there was a function for the opening of Quinn House. At that function there was a chap from the employers side who was in the toilet, downstairs in the building, and he overheard two people say they were going to get rid of [organiser] Steve Hutchins first up, soon as the election went through, and that they would get rid of John shortly after that.

John McLean1

‘Everyone wanted to be top dog’: The 1989 TWU branch elections

At a function at the NSW TWU’s new head office in Parramatta in Sydney’s west in late 1988, John McLean, assistant secretary of the NSW branch, learnt that the TWU elections to be held in the early new year would be the most fiercely contested since the turbulent days of the Cold War and the Great Split in the Labor Party in the 1950s.

Bitter union elections are often the focus of intense personal contests between rival candidates. Between the 1950s and the 1980s, union elections in Australia also reflected the Cold War tensions of the period. The right-wing faction of the labour movement supported a team of candidates. The left-wing candidates often reflected a coalition of Labor Party left-wingers and supporters of the Communist Party of Australia.

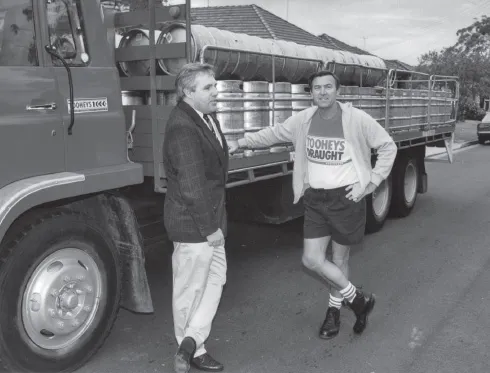

Mixing with the members: John McLean (right) and Steve Hutchins (centre). ‘I think Edwards underestimated how hard we would fight … we didn’t have the delegates but we had the men.’

During the 1950s that Cold War rivalry had played out in the NSW TWU, culminating in the 1959 branch elections, which saw left-wing incumbents defeated by a right-wing ticket led by Ernie Wilmot, initiating a long period of stable right-wing control of the union, reflecting the Labor Right’s ‘social democratic’ approach—politically moderate in Labor Party terms, yet industrially militant, the approach maintained by Ted McBeatty, who followed Wilmot as state secretary.

In the 1970s McBeatty defined the leadership style and union culture subsequently followed by his successors. Steve Hutchins, who worked as a young TWU organiser under McBeatty, says that ‘he was the role model for me personally. I can still think of his saying, “Truckies are industrially militant, but politically conservative.”’2 John McLean remembers a secretary who kept a paternal eye on his organisers. ‘McBeatty was a thorough gentlemen, and he used to call me son. We’d have a few beers and then he’d say, “Time to go home, son.”’3

Ted McBeatty died in a boating accident in 1983. The stability reflected in McBeatty’s approach was maintained until open warfare between rival officials and their rank-and-file supporters erupted in 1988.4 The NSW TWU elections in 1989 provided one of the last, dramatic industrial confrontations of Cold War rivalries in Australia. The elections were conducted as the Cold War ran its course, with the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, leading to the collapse of the Soviet Union and its empire in eastern Europe. The Communist Party of Australia was dissolved in April 1991.

The TWU elections also reflected the new challenges facing the union: a generational change of leadership, emerging as both state and federal governments moved to introduce enterprise bargaining, steadily undermining familiar industry-wide bargaining strategies and settlements arbitrated in formal hearings in the state or federal industrial commissions. Following a decade of declining union membership across Australia from 51 per cent to 41 per cent, and weak union presence in many workplaces—34 per cent of workplaces had no union delegates—it was a period of soul-searching for the labour movement, reflected in the publication of books like What Should Unions Do? by the Labor Council of New South Wales, which sought to open up a debate on new approaches unions could take to recruitment, marketing and organising.5 The transport industry was also changing, with the emergence of new companies and new patterns of work together with increased pressures to meet tighter delivery deadlines. What kind of TWU leadership was required for this new era?

George Clarke, a driver for Tooheys breweries, chose to support Ted Edwards, John McLean’s rival candidate for the position of state secretary. Both Edwards and McLean had long years of experience working in the transport industry, and as officials of the union. By 1988, Edwards was the secretary of the TWU’s Sydney sub-branch, and McLean was the assistant secretary of the state branch. Only one of them could succeed the ailing Harry Quinn.

For George Clarke, Ted Edwards was the fighting underdog, who would take a more aggressive approach with employers. ‘Ted was a bit in your face, like he wanted to give you a whack. He liked a schooner too, so I said, “I’m going with the underdog, I’m going with Ted”, but that was my choice.’

Clarke could also see that John McLean was a strong candidate: ‘I didn’t mind John either … John’s a big lump of a guy, and I thought John probably came across as the right guy … but, you see, in this life, nobody wants to take sides because they’re weak. People are weak.’ There was not too much sign of weakness in the contest between John McLean and Ted Edwards in 1989, as Clarke recalled. ‘Everyone wanted to be top dog. But that’s what happens in this game.’6

On opposite sides in the 1989 TWU ballot: Steve Hutchins and George Clarke.

Sydney sub-branch secretary Ted Edwards (left) in 1988.

The tensions between Edwards and McLean reflected conflicting approaches to the political and industrial direction that each candidate felt the union should take, given the challenges facing the TWU.

In September 1988 Edwards led a controversial three-week strike by 500 owner-drivers demanding an increase in container haulage rates. The strike disrupted freight movements on Sydney’s wharves. Up to $400 million in cargo was held up by the picket lines maintained by the striking drivers. The state government threatened to invoke the Essential Services Act to end the strike, which would have resulted in heavy fines for the union and the drivers.7

Although the drivers had a legitimate grievance, Ted Edwards was accused, according to one press report, ‘by waterfront employers—and by NSW Premier [Nick Greiner]—of stage-managing the waterfront dispute to ensure the support of his main power base: the waterfront cargo carriers’. The report concluded that in the forthcoming TWU elections, ‘Mr Edwards is guaranteed vital votes from the waterfront drivers’.8

George Clarke recalls that ‘Ted was under a lot of pressure … Ted actually stopped all the wharves, there was no boxes coming off the wharves and all the bosses were ringing up and they were taking the union to court … “We’re going to have to stand people down”, which they did. But Ted had to pull it off; otherwise the union would have been heavily fined. So you know, sensible heads have to prevail: “Ted, you have to pull your horns in.”’9

Steve Hutchins had been an organiser with the NSW TWU since 1980 and had experience of working closely with both Edwards and McLean during industrial disputes. Hutchins says that ‘Edwards was good sort of guerrilla leader, but McLean was a general. Edwards could never finish a dispute … he knew how to start it, how to fight it, but he never knew how to finish it and that became very clear [with] the waterfront dispute.’ By contrast Hutchins saw that ‘John [McLean] was very conservative, cautious, particularly in general transport, but in the airlines and oil industry he was very aggressive and he knew exactly when to hit, what to hit. He was very good.’10

Edwards’ election as TWU secretary could also have been politically controversial. McLean observed that ‘[Edwards] was seen to be favouring the Left, which was against the leadership of the [NSW] ALP at that time’. The TWU was a long-standing union affiliate of the state Labor Party, and a traditional supporter of Labor’s right-wing faction.

‘[Edwards] was spending a lot of time, in particular, with the BWIU [the Building Workers Industrial Union, the most powerful of the construction industry unions in Australia],’ McLean said. ‘He was going to their meetings and what have you, so he was certainly getting involved with the Left.’11 Steve Hutchins came to the same view. ‘I think [the BWIU] were up to their neck supporting him and encouraging him. I think he was going to be a Trojan horse.’12

McLean believes Edwards planned to support an amalgamation between the TWU and the left-wing BWIU, which had close ties to the Communist Party. ‘I think that was what was probably planned. Because it would have made a very strong union.’ It was not an amalgamation that McLean, who was aligned with the Labor Right, could support politically.13

Edwards and the BWIU denied the claims of an amalgamation, or a ‘BWIU takeover’ of the TWU. ‘That’s all a fallacy, that’s nonsense,’ George Clarke says. ‘If [Edwards] was close to anybody, it was the MUA [the Maritime Union of Australia, a strong left-wing union on Sydney’s waterfront]. How close he was I don’t know. But as far as the BWIU—that’s all nonsense … bad publicity gets into the papers. It’s like “stop the reds from taking over the TWU”, all that. I used to laugh at it.’14

In the run-up to the elections scheduled for early 1989, Hutchins supported McLean to succeed Harry Quinn as TWU secretary. They were compatible in terms of their approach to industrial strategy and political affiliation: Hutchins was a supporter of the NSW Labor Right, and they shared an interest in survival as TWU officials. As Hutchins observes, Edwards supporters ‘made it very clear that they were going to get me … [T]hey were going to tolerate John for a while, [although] they would have liked to get him there and then.’15

McLean and Hutchins decided on a strategy of lodging their nominations on the last day that nominations could be submitted to the electoral commission. On 29 November 1988 McLean nominated as state secretary and Hutchins nominated as the Sydney sub-branch secretary, leading a ticket of candidates as full-time officers of the union and honorary members of the Branch Committee of Management (BCOM).16

‘We ambushed him,’ Hutchins recalls. ‘[Edwards] didn’t know it was coming, then all of a sudden—bang! It’s on.’ A number of candidates who Edwards assumed would support his ticket had chosen to support McLean’s team. As Hutchins says, ‘There was a lot of people on that ticket, a lot of people knew exactly what was going on and that it was against Edwards.’17

Edwards successfully appealed against the disadvantage to his election ticket, with the NSW Industrial Commission ruling in January 1989 that ‘late’ nominations could be made and that the election would be delayed until March. Edwards said the decision was a ‘slap in the face’ for the McLean team, ‘who had tried every trick in the book to lock me and my team out of this election’.18

Edwards’ anger at being caught off guard by the late nominations inflamed his hostility towards the NSW Labor Party, whom he accused of interfering in the TWU elections in support of the McLean team. There were newspaper reports of Edwards challenging TWU donations to the Australian Labor Party and shifting the TWU delegation’s traditional support at annual Labor Party conferences from the Labor Right to the support of Labor’s Left. Ominously, Edwards added that ‘it would be up to the union’s 33 000 members to decide whether or not they wanted to continue the union’s association with the ALP’.19

Edwards’ threat to end the NSW TWU’s affiliation to the ALP and cut donations could have resulted in the loss to the ALP of up to $100 000 per annum. Without the support of the TWU delegates at Labor Party annual conferences, the Labor Right’s control of the state branch was also threatened. Unsurprisingly, NSW ALP secretary Steve Loosley said that Edward’s stance was ‘retrograde and unfortunate’.20

The election campaign produced some colourful tactics. George Clarke recalls riding through Sydney’s Sutherland Shire on a pushbike, tearing down McLean team posters from telegraph poles. Afterwards, ‘I used to walk into Harry Quinn’s office in Sussex Street and I’d say, “How you doing, Harry?” and he’d say, “I’m not happy about what’s going on. It’s not been a smooth change over”, and I’d used to throw all the pamphlets for the McLean team all over his desk and he’d say, “What the hell is all this?” And I said, “Someone put them up along all the bridges, the Princes Highway and Sutherland and all over the Taren Point bridge, so I took them all down, Harry, and thought I’d give them to you. You can pass them on to the people.” So then he got the shits so me and Harry fell out.’21

Other, more anonymous tactics were less amusing. ‘Those was pretty touchy times, really,’ McLean says. ‘The wife couldn’t make any phone calls’, owing to intimidation directed at him. ‘You never knew who it was. So we had to get a private phone number, and the union phone was on an answering machine so that I could decide whether I wanted to take the call or not.’ Hutchins particularly seemed to attract the hostility of the Edwards team. McLean remembers ‘one of the terms used, f’n, f’n … the educated ones … because he’d been to university. They didn’t like that type of person come up through the ranks...