- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

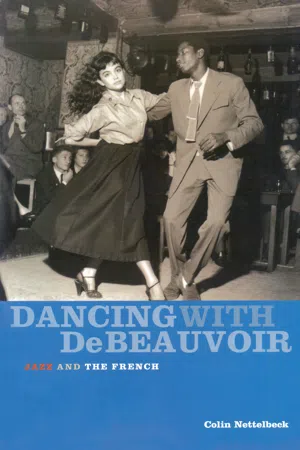

Dancing With De Beauvoir

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

A DIFFERENT MUSIC

Jazz Comes to France

I have to be continually on the lookout to cut out the result of musicians’ originality.

James Reese Europe1

In the Théâtre Graslin in Nantes on 12 February 1918, the atmosphere is one of curious expectancy, tinged with impatience. It is winter, and nobody is aware that the Great War has entered its last year, though with the arrival of massive numbers of reinforcements from North America, hopes are rising. The members of the full-house audience have paid to participate in a celebration of Lincoln’s Birthday, organised in collaboration with the American Army. The women are dressed in their best ceremonial finery, the men in dinner suits or uniforms. They are waiting for the arrival of the official party, already thirty minutes late. On the stage, the musicians of James Reese Europe’s regimental band also wait, sitting silently and neatly in accordance with the discipline imposed by their military training and their leader.

The group of dignitaries finally enters, led by the mayor, who, unperturbed by his own lateness, proceeds to deliver a stirring ten-minute oration. After the applause dies down, the American band—the core and the major part of the evening’s entertainment—begins its concert with the popular French march ‘Sambre et Meuse’, which brings mumurs of enthusiastic recognition from the public. Much of the rest of the concert, however, is filled with music, and song and dance performances, that are completely new to the people of Nantes. Never before have they heard tunes like ‘Negromance’ or ‘Memphis Blues’; above all, they have never heard playing like that produced by this group of all black musicians. They are delighted, dazzled. But how could they be aware of the historical significance of the event in which they are participating?

Most jazz historians acknowledge the performances of James Reese Europe’s band in France in early 1918 as foundational for the French experience of jazz.2 Several other black American military bands were also active in France during this time, often led by musicians whose pedigrees were almost as good as those of Europe. They were considered to be of paramount value to troop morale.3 But James Europe’s band was not only the first to give performances outside the purely military arena; it also captured the imagination of its French audiences in ways that others were unable to do.

Formed in Harlem in June 1916, the 15th New York Infantry Regiment was mustered into active service in the summer of 1917 and arrived in France in late December that year. The US military establishment was endemically racist, with interdictions to prohibit black and white troops serving in the same units and institutional discouragement of any combat training for black soldiers. So, like many other African-American units, the 15th began its service in France in stevedoring and port service in Saint-Nazaire, where the American army had been building up massive installations since June 1917.4 Its eventual participation at the battle front—from 9 April 1918 until the end of September—was made possible only by its integration into the French army, where it was renamed the 369th. This service was deemed to be extremely distinguished, earning the regiment a collective citation and the Croix-de-Guerre.5

The regimental band was formed early in the unit’s existence, and James Reese Europe was recruited as its leader by the enterprising Colonel William Hayward. Europe was already a major figure in the New York popular music scene, as a performer, composer and band leader, with a long list of successes in clubs and musical theatre. Europe recruited his close friend and colleague Noble Sissle, and secured the services of Francis Eugene Mikell, another experienced and well-trained professional. By the time the 15th reached France, the band was a finely tuned ensemble with an extensive repertoire that included anthems and military marches, but also traditional African-American songs (performed with vocals), original compositions by Mikell and Europe himself, and ragtime and blues. Performances were highly syncopated, and included segments where the musicians were released from the constraints of their scores, and—under the close scrutiny of their leader—allowed to improvise.

The concert in Nantes6 marked the beginning of a tour that would take the band across France to Aix-les-Bains, where it spent several weeks entertaining the troops and the local population. The Nantes performance was also part of a local charity drive for the war effort, one of many events organised to demonstrate Franco-American friendship. The streets of Saint-Nazaire and Nantes were often festooned with French and American flags, and large crowds turned out to watch the ‘Sammies’ march to the accompaniment of their military bands.7

From the point of view of the regiment, the Théâtre Graslin performance was a great success. The commander, Captain Arthur Little, recorded the enthusiastic reception:

I doubt if any first night or special performance at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York ever had, relatively, a more brilliant audience. The French people knew no color line. All they seemed to want to know, was that a great national holiday of their ally was being celebrated—and that made the celebration one of their own. The spirit of emotional enthusiasm had got into the blood of our men; and they played as I have never heard them play before.8

The perceived absence of a ‘color line’ was a central factor in the sense of triumph experienced by members of the band. Tyler Stovall draws attention to the myth of a ‘color-blind France’, proposing that ‘the idea of France as a refuge from American racism had far more to do with conditions in the United States than conditions in Paris’.9 However, there is no doubt that the musicians had a genuine impression of being accepted and praised for their artistry and originality, a perception integral to their ‘emotional enthusiasm’. Noble Sissle half-humorously reached the conclusion that the band’s performance brought the French something more important than military aid:

Colonel Hayward has brought his band over here and started ‘ragtimitis’ in France; ain’t this an awful thing to visit upon a nation with so many burdens? But when the band had finished and people were roaring with laughter, their faces wreathed in smiles, I was forced to say that this is just what France needs at this critical time.10

These American assessments of the event, based as they are on feelings of shared patriotic and artistic values, are no doubt accurate enough. However, when one turns to how the French themselves experienced the occasion,11 it becomes apparent that the reception of the music by the audience in Nantes was rather more complex.

In 1918, the city of Nantes boasted a population of around 150 000 and a lively daily press, notably Le Populaire and Le Phare de la Loire. Both papers ran announcements of the concert for some days beforehand, under the heading ‘Manifestation franco-américaine’. The publicity build-up was handled with an eye to ensuring the concert’s success. On 9 February, both papers included a fall program.12 The next day they concentrated on the attraction of the music (although describing it as being ‘in some ways analogous to that of the naval bands in France’), and the reputation of the musicians (with Europe and Mikell described as ‘two eminent artists’). On the 11th, Le Populaire stressed the significance of honouring the memory of President Lincoln, and the planned presence, at the event, of the notables of Nantes, various allied generals, and the Consul-General of the United States: what had seemed originally to be an entertainment for charity purposes had begun to take on a greater political dimension. This article ends on a couple of intriguing notations:

An American band, led by an American conductor, with a considerable reputation on the other side of the Atlantic will perform a representative program made up of American pieces and songs.

All the musicians of the ‘New York Infantry Band’ are ‘color gentleman’ [sic] whom the citizens of Nantes will make a point of honour of hearing, acclaiming and applauding.13

This is the only reference, in the entire reporting of the event, to the fact that the musicians were black. Given the emphasis on the American character of the orchestra, the conductor and the music, the reference to ‘color gentleman’ seems bizarre. Is it simply a bit of novelty and exoticism for publicity purposes? Could it be that the writer is transmitting information provided by the band itself, the members taking pride, as African-Americans, in its national ambassadorial role? Certainly there is no suggestion of any real ‘colour consciousness’, or anything that would invalidate Captain Little’s observation that the French ‘knew no color line’. For Le Populaire, James Europe’s orchestra and music were as American as Lincoln’s birthday.

The celebration of Lincoln’s birthday began with an all-male gala banquet hosted by the Mayor, Paul Bellamy, at the Hôtel de France. Among the sixty guests at the lavishly decorated tables were the Prefect, the French military and naval chiefs stationed in the region, the civic and business leaders of Nantes, and the Consuls of Britain, Italy and Belgium. On the American side, the guests of honour were General Walsh, commander of the American base in Saint-Nazaire, and the Consul-General of the United States, accompanied by his vice-consuls, together with a large group of American army and naval officers. After dinner, over champagne, the American Consul-General delivered, in French, a carefully crafted speech, the full text of which was published in both newspapers the following day.

The Consul-General evoked the traditional friendship binding France and his nation, pre-dating La Fayette and based on the common ideal of liberty: an ‘alliance of hearts’ that would last forever because it was ‘ordained not by man but by the Grand Master of the Universe’. Just as France helped America when it was fighting for its independence, so now the Americans had come to help France, and they did so ‘without ulterior motive’, out of love for the nation and its people. This was no territorial war, but the defence of modern civilisation against the barbarity of Prussian militarism: ‘We have come to help France safeguard democracy in the world.’

The speech paid homage to the passion and bravery of the French army and to the endurance and suffering of the people. France would rise again, and ‘shine with a lustre brighter than ever ... as the emblem of the rights of man’. In the tail of the speech, however, there was a sting. In retrospect, the Consul’s words seem to prefigure a new consciousness of America’s potential as an international force, and the determination to create a new world order. In such a global context, Franco-American ‘affinity’, and indeed France itself, would have diminished importance:

We shall conquer and the colours of France and America like those of Great Britain, Italy, Belgium, Brazil, Japan and the other allied states will fly more serenely than ever in a world where individual freedom will exist along with the autonomy of nations in a League of Nations, in which treaties will be considered as sacred, and where arbitration will take the place of force, in a climate where honour and justice can reign. Long live France! Long live Brittany! Long live the city of Nantes!14

It is not surprising that the Wilsonian postwar program should find its way into the Consul-General’s speech, which was greeted with warm applause; and no doubt the good people of Nantes were flattered by the three-part final salutation, which so clearly moved its focus from the national to the local.

The shadow of difference between the American position and the French one darkens when we look closely at the response given by the Mayor before his compatriots in the Théâtre Graslin. Using the example of Lincoln, he introduced his first major theme, liberty:

Our wish for the whole universe is what the New World has achieved: to unite rather than to divide, to bring down the old forces of domination and tyranny with their dark Machiavellian schemes, and in their place to ensure the triumph of fresh energies of integrity, transparency and, indeed, political honesty.15

In the Mayor’s mind, America appeared as a selfless provider of resources, undemanding and uncomplicated, to participate in sacrifice for the abstract ideals of justice and liberty.

The idea of partnership introduced the Mayor’s second theme, that of equality. He acknowledged differences between the Old World and the New, but saw their destinies as convergent:

. . . When victory has rewarded our persistence and when its fruits have repaid all the blood that has alas been shed, allow us to hope that your youthful ardour will not turn its back on our old civilisation . . . Europe and America cannot be rivals: they will work together, they will construct the League of Nations which, first and foremost, will be the League of Peoples who have desired the liberty of the world, the League of Allies.16

The explicitly European dimension of Bellamy’s discourse is striking. To embrace the New World does not imply any weakening of Europe as a centre, but rather the prospect of an exchange of goods and culture that will produce ‘greater well-being and a greater sense of fraternity’.

Liberty, equality, fraternity: unlike the American Consul-General’s intimations of a new global order, the Mayor’s speech was structured by the universalist values of the French Revolution. It was through these values that France, in welcoming the American presence, could offer hope for the future:

Patience, gentlemen! The garden-beds will flower again and tomorrow, you and all our allies will carry from our home to yours the roses and laurels of the land of France.17

The confidenc...

Table of contents

- DANCING WIth DeBEAUVOIR

- Contents

- List of photographs

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- CHAPTER 1 A DIFFERENT MUSIC

- CHAPTER 2 SETTLING IN

- CHAPTER 3 REVIVAL AND REVOLUTION

- CHAPTER 4 FRENCH JAZZ COMES OF AGE

- CHAPTER 5 FOLK HOT OR MODERN COOL?

- CHAPTER 6 MAKING CROCODILES DAYDREAM

- CHAPTER 7 DANCING WITH DE BEAUVOIR

- CHAPTER 8 ‘IΝ ONE WORD: EMOTION’

- CHAPTER 9 NON-STOP AT LE JOCKEY

- Notes

- Chronology

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Dancing With De Beauvoir by Colin Nettelbeck in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.