eBook - ePub

Crossing Cultures

Conflict, Migration And Convergence

Jaynie Anderson

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Crossing Cultures

Conflict, Migration And Convergence

Jaynie Anderson

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Crossing Cultures by Jaynie Anderson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

History of Art1

A Melbourne Conversation at the Town Hall on Art, Migration and Indigeneity

What Happens when Cultures Meet?

1

An Introduction to the Conversation

One of the interesting and important aspects of the Melbourne CIHA conference was the high level of public recognition and involvement. Jaynie Anderson, the conference convenor, supported by the organising committee, had recognised at an early stage that a broad-based media and PR campaign would greatly assist the successful delivery of the conference, not only helping with the provision of sponsorship and in-kind support, but also responding to what was anticipated would be a high level of interest within the arts-oriented sector of the general public. This proved to be the case.

The City of Melbourne proposed that one of its ‘Melbourne Conversations’ series be dedicated to the subject of the conference. This long-standing series of free public talks at the Town Hall has regularly offered Melbourne audiences access to high-profile international experts on a variety of subjects, often arranged to coincide with a major conference or event which in itself has attracted broad public awareness. The CIHA Conversation was no exception. As an unticketed event, it was impossible to count accurately the number who attended, but Town Hall staff estimated the audience at 1200, making it the most attended of all the Conversation events. Although not necessarily predicted, this high level of interest was not perhaps surprising in a cosmopolitan city whose culture throughout its history has constantly evolved, and has been enriched, through waves of immigration. The National Gallery of Victoria’s own visitor research has regularly indicated that it has one of the highest community participation rates for any equivalent institution in the world, with 75 per cent of its 1.7 million visitors (the figure for 2007) coming from Melbourne itself or its environs. Each of the speakers proffered the view that it was the largest live audience they had ever addressed.

The themes and ideas that emerged from the presentations concerned concepts of globalisation; the fluidity with which art objects move through space and time; how this mobility defines and influences national, regional and individual attitudes to cultural property and repatriation claims; postcolonial identity politics; and a new and refreshing emphasis on Indigenous art histories, long under-represented on the world stage.

In her remarks, the outgoing president of the CIHA Ruth Phillips, whose own field of research concerns comparative art history and anthropology (especially North American), observed that it was appropriate that the presidency was passing from Canada to Australia, reinforcing the possibilities for seeing world art history from perspectives other than the European.

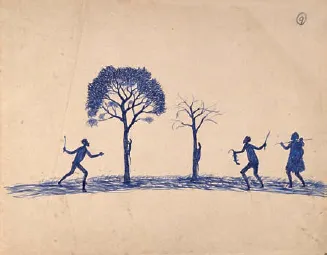

This idea was introduced by the first speaker, Jaynie Anderson, who suggested that the conference theme, ‘Crossing Cultures: Conflict, Migration and Convergence’, could be seen as a metaphor for the social and cultural experience of all Australians, Indigenous and non-Indigenous. Professor Anderson referred to nineteenth-century Indigenous artist Tommy McRae, observed and depicted European colonists in relation to his own culture and tradition, and concluded with Kenneth Clark’s enthusiastic response to Indigenous Australian art first encountered during his visit in 1949. In the context of European (especially Anglicised) postcolonial society in Australia, she also described how in the 1940s and 1950s a new generation of postwar immigrants, many of the most important from non-British backgrounds, effectively created the study of art history in Australia, and brought new and challenging perspectives.

Ronald de Leeuw, no stranger to Australia and Melbourne through several extended visits and therefore well aware of issues relating to the emergence of Indigenous art in the consciousness of European Australians, began his thought-provoking paper with the statement ‘Transformation is the natural state of the arts’. He described how the rise of Dutch art and visual culture, especially in the seventeenth century, reflected and imitated the trading concepts of ‘give and take’, with Dutch artists absorbing influences from Asia in particular, but also exporting Dutch cultural experience and ideas to other parts of the world. He concluded with the welcome reasurrance that ‘art is a delightful cocktail’.

Howard Morphy, one of Australia’s leading experts in the field of Indigenous visual culture and social anthropology, reviewed the rise of contemporary Indigenous art and its critical reception, noting the gradual shift within Australia towards seeing this as fine art as opposed to ethnography, and ultimately arguing for a new approach, given the un sustainability of maintaining the traditional anthropology versus art history oppositions. He concluded with some reflections on the necessity, and complexity, of producing Indigenous art histories relevant on their own terms and not necessarily through European Australian attitudes.

Michael Brand broadened the debate with reflections on works of art as citizens and migrants, evoking the specific histories of particular works of art on the move, and confronting head-on the dilemma faced by all collecting institutions, namely how to present in a meaningful way the cultures of other countries and times in the face of valid concerns about illegal excavations, trafficking and patrimony claims. He commented frankly on the trafficking and repatriation issues that have recently engulfed the Getty. A key aspect of ‘Crossing Cultures’ is the migration of works of art, and an important and enduring concern of the study of art history is the movement of art between cultures and continents, leading so often to a conflict between notions of enlightened cosmopolitanism and cultural nationalism.

Ruth Phillips concluded the formal presentations with reflections on Indigenous art histories and related issues concerning ‘twenty-first-century cultural politics’ and demands for repatriation, particularly in relation to a major Indigenous Canadian chief’s outfit presented to the Museum of Victoria at the end of the nineteenth century. Her paper above all contrasted mid to late nineteenth-century attitudes about the idea of global cultural exchanges with the rejection of these Eurocentric ideas and values in the context of early twenty-first-century postcolonial Indigenous perspectives.

This concentration on the material and visual culture of Indigenous North Americans provided a natural prelude for the concluding remarks from Francesca Cubillo, offering an Indigenous Australian perspective on many of the issues raised in the papers. In a moving impromptu speech, Ms Cubillo reviewed issues concerning ownership and repatriation, insisting that the issues be understood from an Indigenous perspective, and her views received strong support through applause from the audience.

Tommy McRae Kwatkwat, c. 1835–1901 Hunting Figures, c. 1891 Illustration no. 9 from Sketchbook 24.4 × 31.2 cm (image and sheet) pen on blue ink on paper National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Purchased with funds donated by Ian Hicks AM, John Higgins and two anonymous donors, 2008

At the conclusion of the Conversation, Professor John McPhee, Deputy Vice-Chancellor for Academic Affairs, thanked the speakers on behalf of the University of Melbourne, and drew the proceedings to a close.

The Melbourne Conversation, on the first full day of the conference, succeeded in drawing broad public attention to many of the key issues that were to be discussed in the following days. Above all, these papers raised the possibility that the physical presence of the conference in the Southern Hemisphere, in a country in which Indigenous culture has newly asserted itself as a powerful force and which, because of its geographical position, inevitably has a different perspective on the cultures of Asia and the Pacific, might encourage fresh thinking about crossing cultures and global art history.

2

Playing between the Lines

The Melbourne Experience of Crossing Cultures

Whoever invented the CIHA conference system intended that the art historians who have the honour to be the convenors of an international art history congress such as we are holding in Melbourne have a unique opportunity to assess the practice of art history throughout the world at a particular moment in time. This singular privilege is not reflected in the literature on the subject of global art history. The concept for the congress was intended to elicit a global response, and as the size of the audience present at the Town Hall (1200 people) has revealed, it has been spectacularly successful. There are contributions from participants from fifty countries, despite the fact that we in the Antipodes live so far away from the rest of the world. To date only thirty-three countries belong to the international art historical organisation—I hope that under my presidency of the CIHA those colleagues from new countries who came to Melbourne will become members.

The extraordinarily popular map of Australia devised by David Horton in 1996 as an illustration for the Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia charts more than 300 Indigenous languages, clans and dialects in our country (see figure 1). It is a striking visual demonstration of how the concept of the cross cultural is deeply rooted in the very landscape of our populations. It shows the remarkable linguistic diversity of Indigenous Australian populations and represents Aboriginals as many different interacting groups with different languages, some being as different as, say, Hungarian from Russian. Perhaps what makes the map so popular is the sophistication of the myriad cross-cultural interactions.

In accounts of world art history such as James Elkins’s often-quoted volume Is Art History Global? Australia is mentioned only once, in an inaccurate statistic.1 When an Australian does make an appearance in art history, he inevitably stands for a ‘primitive’, one who knows nothing of Europe. Take the case of Erwin Panofsky’s Studies in Iconology, in which ‘an Australian bushman’ makes a surprising appearance in the company of ‘an ancient Greek’ as a person who would not understand the significance of a European gesture such as ‘lifting a hat’.2 ‘Our Australian Bushman’, Panofsky wrote, ‘would be equally unable to recognise the subject of a Last Supper; to him, it would only convey the idea of an excited dinner party’.3 Anyone who saw the film Crocodile Dundee would know that the Australian bushman Paul Hogan does raise his Akubra hat, to take over New York with the traditional greeting ‘G’day’.

What could the average Australian bush man have known about art, whether he was Indigenous or non-Indigenous? He would almost certainly have had privileged contact with the imagery of ancient rock art, dated in this example some 38 000 years ago, that is to be found throughout Australia but conspicuously at the Top End (see figure 2). Australia has the largest continuous record of any country in...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 A Melbourne Conversation at the Town Hall on Art, Migration and Indigeneity: What Happens when Cultures Meet?

- 2 Creating Perspectives on Global Art History

- 3 Art Histories in an Interconnected World:Synergies and New Directions

- 4 The Idea of World Art History

- 5 Fluid Borders: Mediterranean Art Histories

- 6 Hybrid Renaissances in Europe and Beyond

- 7 Cultural and Artistic Exchange in the Making of the Modern World, 1500–1900

- 8 Representations of Nature across Cultures before the Twentieth Century

- 9 The Sacred across Cultures

- 10 Materiality across Cultures

- 11 Memory and Architecture

- 12 Art and Migration

- 13 Art and War

- 14 Art and Clashing Urban Cultures

- 15 Global Modern Art: The World Inside Out and Upside Down

- 16 Indigeneity/Aboriginality, Art/Culture and Institutions

- 17 Parallel Conversions: Asian Art Histories in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries

- 18 Contemporaneity in Art and Its History

- 19 New Media across Cultures

- 20 Economies of Desire: Art Collecting and Dealing across Cultures

- 21 New Museums across Cultures

- 22 Repatriation

- Index of Authors