eBook - ePub

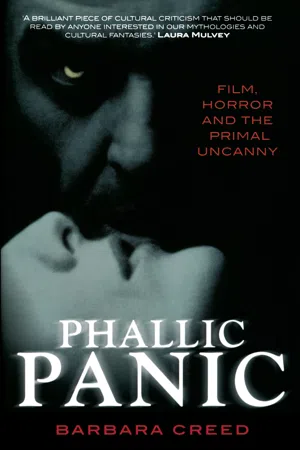

Phallic Panic

About this book

Vampires, werewolves, cannibals and slashers-why do audiences find monsters in movies so terrifying? In Phallic Panic, Barbara Creed ranges widely across film, literature and myth, throwing new light on this haunted territory.Looking at classic horror films such as Frankenstein, The Shining and Jack the Ripper, Creed provocatively questions the anxieties, fears and the subversive thrills behind some of the most celebrated monsters.This follow-up to her influential book The Monstrous-Feminine is an important and enjoyable read for scholars and students of film, cultural studies, psychoanalysis and the visual arts.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Publisher

Melbourne University Press DigitalYear

2015Print ISBN

9780522851724eBook ISBN

97805228690571 FILM, HORROR AND THE PRIMAL UNCANNY

Dismembered limbs, a severed head, a hand cut off at the wrists ... all these have something peculiarly uncanny about them ... being buried alive ... intra-utérine existence ...the female genital organs ...

SIGMUND FREUD1

Doubles, automata, ghosts, witches, vampires, waxwork figures, haunted houses, severed body parts, women’s genitalia, the undead—according to Sigmund Freud, all of these and more constitute the domain of the uncanny. The uncanny evokes fear, unease, disquiet and gloom; it ‘is undoubtedly related to what is frightening—to what arouses dread and horror’.2 These images and emotions also characterise a great deal of popular cinema, particularly films belonging to the categories of horror, science fiction and the surreal. Over recent years there has been a renewed interest in the uncanny and a number of important studies have appeared across a range of disciplines—from literature to feminist theory, architecture and film.3

In his famous essay ‘The Uncanny’ (1919), Freud developed a substantial theory of the uncanny. In the first section of the essay he considers a range of etymological sources of the uncanny as well as the writings of Jentsch and Schelling on the meaning of the uncanny. Next he offers an interpretation of ‘The Sandman’, an important short story by Ε. T. A. Hoffman, whom he describes as ‘the unrivalled master of the uncanny in literature’. In The Sandman’, Freud argues, ‘the feeling of something uncanny is directly attached to the figure of the Sandman, that is, to the idea of being robbed of one’s eyes’.4 ‘The Sandman’ tells the story of Nathaniel, who as a boy develops an unnatural fear of a certain lawyer, Coppelius, who he believes is the dreaded sandman. The sandman steals the eyes of children who won’t go to sleep. He ‘throws handfuls of sand in their eyes so that they jump out of their heads all bleeding’.5 Coppelius is a friend of Nathaniel’s father—the two men appear to be engaged in a mysterious experiment that suggests they are trying to create artificial life.

As a young man, Nathaniel, who has never resolved his infantile fears, becomes engaged to Clara, a distant relative, who along with her brother came to live with Nathaniel and his mother when they were orphaned. Nathaniel also falls in love with a mysterious lifelike doll, Olympia, who he fails to realise is not human. He believes that the doll is actually the daughter of his neighbour, Professor Spalanzani. At the same time, he believes the local clockmaker, Coppola, is none other than the terrible Coppelius, or the sandman. Coppelius and Professor Spalanzani have created Olympia together. Nathaniel learns the truth about Olympia when he sees her eyes fall from her head, leaving gaping holes. In the end he commits suicide by jumping from a parapet.

Freud argues that the sandman, who he equates with the castrating father, is the true source of the uncanny. He disagreed with Ernst Jentsch who, in his 1906 essay ‘On the Psychology of the Uncanny’, argued that a powerful source of the uncanny is ‘intellectual uncertainty whether an object is alive or not and when an inanimate object becomes too much like an animate one’.6 After discussing Hoffman’s story, Freud presents a series of objects, events and sensations that he argues are uncanny. Freud places much importance on the threat of loss and castration—the threatening father figure, severed limbs, loss of eyes, death. In conclusion, he discusses the representation of the uncanny in literature and other forms of the creative arts.

In his essay, Freud turned to a neglected area belonging to the field of aesthetics because he believed that psychoanalytic theory could help to illuminate this issue. He was interested not in the theory of beauty but in ‘the theory of the qualities of feeling’. He pointed out that academic treatises usually prefer to explore the question of which ‘circumstances and objects’ call forth ‘feelings of a positive nature’ that are associated with ‘the beautiful, attractive and sublime’.7 He was interested in a related but opposite question. What is it about frightening people, things, impressions and events that arouse ‘dread and horror’, ‘repulsion and distress’?8 ‘One is curious to know what is this common core that allows us to distinguish as “uncanny” certain things that lie within the field of what is frightening.’9 The uncanny, however, is not necessarily reducible to the general emotion of fear. ‘[The uncanny] is not always used in a clearly definable sense, so that it tends to coincide with what excites fear in general. Yet we may expect that a special core of feeling is present which justifies the use of a special conceptual term.’10

From the outset Freud defined the uncanny as ‘that class of the frightening which leads us back to what is known of old and long familiar’.11 His aim was to demonstrate the circumstances in which ‘the familiar can become uncanny and frightening’.12 He was particularly interested in the secret side of the uncanny, and noted with interest Schelling’s definition of unheimlich as ‘the name for everything that ought to have remained ... secret and hidden but has come to light’.

Freud traced the meaning of the uncanny through many languages. The definition of what is frightening relates to what is unfamiliar and derives from the German word unheimlich:

The German word ‘unheimlich’ is obviously the opposite of ‘heimlich’ [‘homely’], ‘heimisch’ [‘native’]—the opposite of what is familiar; and we are tempted to conclude what is ‘uncanny’ is frightening precisely because it is not known and familiar ... Something has to be added to what is novel and unfamiliar in order to make it uncanny.13

For the unfamiliar to be rendered uncanny it needs to be something, as Schelling put it, that should have remained out of sight. Theorist Rosemary Jackson has argued that this definition gives an ideological or ‘counter cultural’ edge to the uncanny14 In other words, the uncanny has the power to undermine the social and cultural prohibitions that help to create order and stability.

Freud was particularly interested in the relationship of the uncanny to the ‘home’—an important connection for this study, as so much horror originates in the home. Heimlich is used to refer to places such as the home, a friendly room, a pleasant country scene, a person who is friendly, or a family. It can also refer to a secret place or action, an act of betrayal (behind someone’s back), to someone unscrupulous. Freud points out that one of the most important things about the term heimlich is that it contains a double meaning: heimlich also signifies its opposite meaning and is used to signify unheimlich.

In general we are reminded that the word heimlich is not unambiguous but belongs to two sets of ideas, which, without being contradictory, are yet very different: on the one hand it means what is familiar and agreeable; on the other, what is concealed and kept out of sight. Unheimlich is customarily used, we are told, as the contrary only of the first signification of heimlich and not the second.15

So, heimlich can signify its opposite, it can come to have the meaning usually given to unheimlich. It can mean ‘that which is obscure, inaccessible to knowledge’.16 Thus the term itself has a double meaning: ‘heimlich is a word the meaning of which develops in the direction of ambivalence, until it finally coincides with its opposite unheimlich. Unheimlich is in some way or other a subspecies of heimlich’.17

The double meaning of heimlich is important to a discussion of the uncanny as it underlines the close association between these two concepts: homely/unhomely; clear/obscure; knowable/unknowable. When referring to the familiar/unfamiliar nexus I have used the terms heimlich and unheimlich throughout the book; otherwise I use the term ‘uncanny’. One can easily turn into the other. This double semantic meaning is important for a discussion of the workings of the uncanny in film as the latter is often produced at the border, at the point of ambivalence, when for instance the friendly inviting place of refuge suddenly becomes hostile and uninviting, or the cheerful welcoming host becomes cold and frightening. Unheimlich can be used as the opposite of heimlich only when the latter signifies the homely. When used as a separate term, unheimlich means ‘eerie, weird, arousing gruesome fear’. It signifies the ‘fearful hours of night’, a ‘mist called hill-fog’, everything ‘secret and hidden’.18

It was Schelling’s statement—that the uncanny is that which ought to have remained hidden but has come to light—that gave Freud the insight he needed to elaborate an aesthetic theory of the uncanny and its effects. Freud states that Schelling ‘throws quite a new light on the concept’, in that heimlich can also refer to the act of concealing. Freud includes a biblical reference (1 Samuel, ν 12) that refers to ‘Heimlich parts of the human body, pudenda’.19 This aspect of the uncanny no doubt influenced Freud’s final definition, in which he includes a category relating to the female genital.

The key to the uncanny, Freud argued, is repression. The uncanny is that which should have remained repressed (a different meaning from ‘secret’ or ‘hidden’) but which has come to light. As mentioned, Freud disagreed with Jentsch, who argued that the major feature in the creation of an uncanny feeling is intellectual uncertainty. In his analysis of the Hoffman short story ‘The Sandman’, Freud concluded that repression, in relation to the boy’s castration anxiety, was a more important source of the uncanny than intellectual uncertainty about whether an object, such as the doll Olympia, is animate or inanimate.

Freud argued that the uncanny signifies the return of an earlier state of mind associated either with infantile narcissism or primitive animism. He concluded that there are two classes of the uncanny: one associated with psychical reality, which is most likely to occur in relation to repressed infantile complexes such as the castration complex and womb phantasies; and the other relating to the ‘omnipotence of thoughts’ grouping and associated with physical reality. The two groups, however, are not necessarily easily distinguished.

Our conclusion could then be stated thus: an uncanny experience occurs either when infantile complexes which have been repressed are once more revived by some impression, or when primitive beliefs which have been surmounted seem once more to be confirmed.20

Freud points out that events associated with the ‘omnipotence of thoughts’ category are not always uncanny. While the strongest forms of the uncanny relate to infantile complexes such as castration complexes and womb phantasies, ‘experiences which arouse this kind of uncanny feeling are not of very frequent occurrence in real life’ in comparison with fiction and other creative practices.21

Freud concluded that the uncanny as it is represented in creative works deserves a separate discussion for it is ‘a much more fertile province than the uncanny in real life’.22 In the creative arts, the subject matter is not necessarily exposed to reality testing, and there are many more ways of creating uncanny effects. When the author moves into the world of reality—as distinct from fantasy—he or she has the power to create, increase and enhance anything that might lead to an uncanny effect, even creating ‘events which never or very rarely happen in fact’.23

The cinema, particularly the horror film, offers a particularly rich medium for an analysis of contemporary representations of the uncanny. In his book The Uncanny, Nicholas Royle rightly points out that the uncanny is not necessarily associated with strange objects, events and sensations that terrify. ‘The uncanny can be a matter of something gruesome and terrible ... But it can also be a matter of something strangely beautiful, bordering on ecstasy (“too good to be true”), or eerily reminding of something like déjà vu.’24

In his discussion, Freud establishes a series of categories of the uncanny—all of which will provide a basis for analysis of the uncanny effects of the films discussed in the following chapters. These are: castration anxieties represented through dismembered limbs, a severed head or hand, being robbed of the eyes, fear of going blind or a fear of the female genitals; uncertainty as to whether an object is alive or dead, animate or inanimate—as in dolls and automata; those things that signify a double: a twin, a cyborg, a doppelgänger, a ghost or spirit, a multiplied obje...

Table of contents

- PHALLIC PANIC

- CONTENTS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- 1 FILM, HORROR AND THE PRIMAL UNCANNY

- 2 FILM AND THE UNCANNY GAZE

- 3 MAN AS WOMB MONSTER: FRANKENSTEIN, COUVADE AND THE POST-HUMAN

- 4 MAN AS MENSTRUAL MONSTER: DRACULA AND HIS UNCANNY BRIDES

- 5 FREUD’S WOLF MAN, OR THE TALE OF GRANNY’S FURRY PHALLUS

- 6 FEAR OF FUR: BESTIALITY AND THE UNCANNY SKIN MONSTER

- 7 FREDDY’S FINGERNAILS CHILD ABUSE, GHOSTS AND THE UNCANNY

- 8 JACK THE RIPPER: MODERNITY AND THE UNCANNY MALE MONSTER

- NOTES

- FILMOGRAPHY

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX