Medieval Greece

Encounters Between Latins, Greeks and Others in the Dodecanese and the Mani

- 342 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Medieval Greece

Encounters Between Latins, Greeks and Others in the Dodecanese and the Mani

About This Book

Medieval Greece brings together twelve articles by historian Michael Heslop, showcasing his long-standing interest in the medieval castles of Greece.

Ten of the articles in this volume focus on the Dodecanese islands, mainly Rhodes, at the time of their rule by the Hospitallers during the period 1306–1522. Scholarly and popular interest in the military orders has grown substantially over the last twenty years, but comparatively little has been written about the Hospitaller Dodecanese. What distinguishes this work is the author's use of hitherto unpublished documents from the Hospitaller archives in Malta and his assiduous field work on the island sites discussed. Heslop's work on the Hospitallers on the island of Rhodes has also enabled him to put together an important gazetteer of place-names in the countryside of Rhodes, published here for the first time. The remaining two chapters of the collection summarize ground-breaking detective work to locate Villehardouin's 'lost' castle of Grand Magne in the Mani, and present a wider study of Byzantine fortifications in medieval Greece.

This book will appeal to scholars and students of medieval history, and to all those interested in the history of the Hospitallers. (CS1093).

Frequently asked questions

1

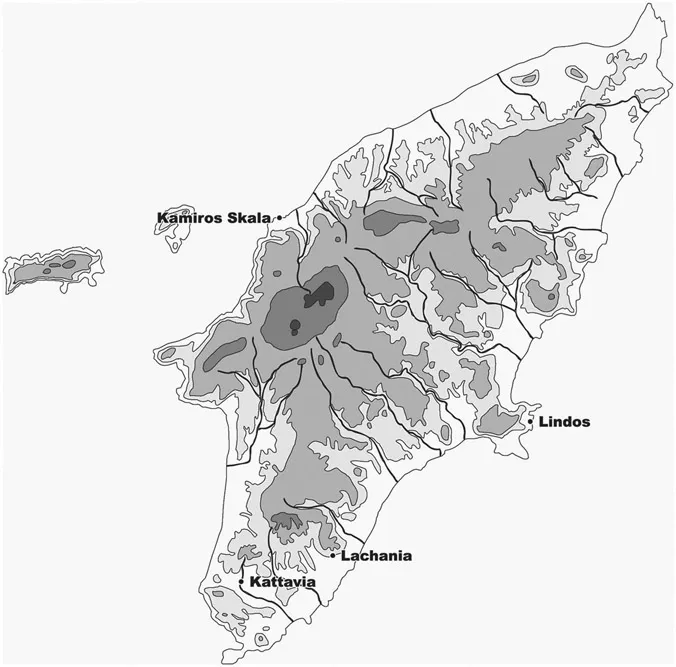

THE SEARCH FOR THE DEFENSIVE SYSTEM OF THE KNIGHTS IN SOUTHERN RHODES

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of maps

- List of tables

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 The search for the defensive system of the Knights in Southern Rhodes

- 2 The search for the defensive system of the Knights in the Dodecanese (Part I: Chalki, Symi, Nisyros and Tilos)

- 3 The search for the defensive system of the Knights in the Dodecanese (Part II: Leros, Kalymnos, Kos and Bodrum)

- 4 Hospitaller statecraft in the Aegean: island polity and mainland power?

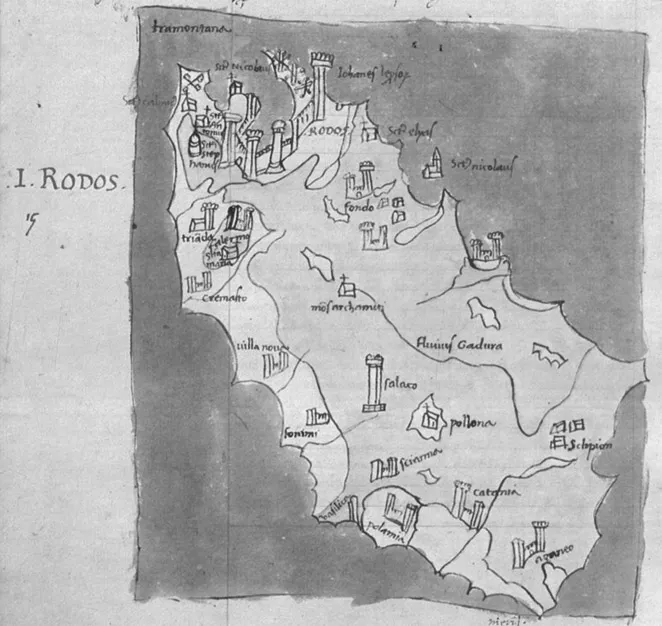

- 5 The countryside of Rhodes and its defences under the Hospitallers, 1306–1423. Evidence from unpublished documents and the late medieval texts and maps of Cristoforo Buondelmonti

- 6 Defending the frontier: the Hospitallers in Northern Rhodes

- 7 Rhodes 1306–1423: the landscape evidence and Latin-Greek cohabitation

- 8 A Florentine cleric on Rhodes: Bonsignore Bonsignori’s unpublished account of his 1498 visit

- 9 The defences of Middle Byzantium in Greece (seventh–twelfth centuries): the flight to safety in town, countryside and island

- 10 Prelude to a Gazetteer of place-names in the countryside of Rhodes 1306–1423: evidence from unpublished documents

- 11 Villehardouin’s castle of Grand Magne (Megali Maini): a re-assessment of the evidence for its location

- 12 A Gazetteer of place-names in the countryside of Rhodes 1306–1423

- Bibliography

- Index