![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Exegesis of Unifying Biology

Things taken together are whole and not whole, something which is being brought together and brought apart, which is in tune and out of tune; out of all things there comes a unity, and out of a unity all things.

Heraclitus

I believe one can divide men into two principal categories: those who suffer the tormenting desire for unity, and those who do not.

George Sarton

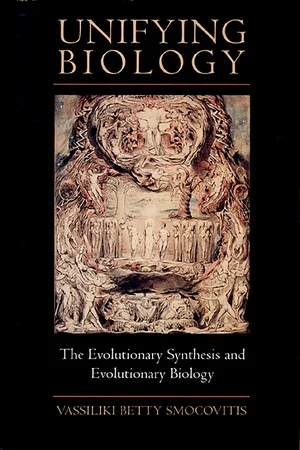

MORE THAN any preface, prologue, or introduction, the image of William Blake’s Fall of Man immediately captures (powerfully so) the undergirding themes of Unifying Biology.1 On the surface, Blake’s image retells the Biblical origin story of Western “Man.” Because they partook of the fruit from the tree of knowledge—on Woman’s urging—Man and Woman are expelled from the Garden of Eden and sentenced to live between the contrasting worlds of heaven and hell.

Yet the image also carries meanings deeper than this surficial—and somewhat conventional—account of “Man’s” origin.2 In composing the image, Blake studiously divided key components into paired dualities or oppositional images, forming the extremities of the text:3 God and Satan, Man and Woman, the Tree of Life and the Tree of Knowledge, Good and Evil, Life and Death. These dichotomous elements are obvious to the reader and hardly need closer interpretation; not so obvious, however, is the duality represented by elements in the center and at the periphery of the text. Appearing to exist as the sole figure centrally located, the clothed body of Christ serves as the unifying principle or centrifugal force of the text; it is counterbalanced by the centripetal forces represented by the swirling vortex of naked humanity at the periphery of the text. While the Christ-figure is bathed in a glowing light representative of Edenic tranquility, the multiple mass of humanity appears darkened, inverted, and unstable. While the solitary figure of Christ exists in an eternal, unchanging world, the crowded mass of humanity exists within a world of never-ending change. Entering a world whose centripetal forces threaten to disrupt existence, Man and Woman maintain physical—and spiritual—connection to the centrifugal force emanating from the Christ-figure. Though they are on the path leading toward hellfire and damnation, they are also on the same path that leads to paradise and salvation. The only hope of transcendence—to override or rise above the earthly world—comes by following the figure of Christ from the world of innocence to the world of experience.

Blake’s religious imagery in the Fall of Man may appear far removed from modern scientific belief, the subject of this work. It may appear to be especially far removed from modern evolutionary science, which has arguably offered an account of human origins that has substituted (if not subverted outright) the Biblical narrative represented in Blake’s Fall of Man. Yet many of the themes in Blake, I would argue, run equally deep within the narrative of the history of science in the West.4 Among these are the need to reconcile, to bring to line, to unify within a single, all-embracing, coherent, and logical system of thought those divergent—and diverse—elements that threaten to disrupt an orderly world. From Heraclitus, who sought the one in many, to Plato, who cherished the unity of knowledge, to the Enlightenment philosophers who sought to unify the branches of knowledge within a systematic and universal scheme, to the generations of positivists who dreamt of unifying the sciences, the narrative of the intellectual history of the West includes tales of heroic figures seeking unity in diversity, eternity within impermanence, and order in disorder. Solitary figures seeking the meaning of life, such individuals also came together in collectives, building communities on common ground, sharing a belief in and a search for transcendent truths. Though traditionally set apart, and frequently seen at odds with each other, myth, religion, and science all share the same quest for universal, absolute, transcendent truths.5 All three share a common opposition to views that deny the existence of transcendent truths in favor of local, relative, or otherwise “embodied,” “contextual” forms of knowledge.

A similar tension between opposing points of view at the center versus the periphery of the text has made its way into contemporary intellectual circles via the introduction of multiculturalist sociopolitical theory. Using various devices to subvert, defuse, or deconstruct existing power structures inherent in any universalizing or totalizing systems, the goal of the multiculturalist project is to “give voice*’ to the diversity of positions silenced or marginalized by moves toward unity. While it appears an ideological political action program, multiculturalism also rests tremulously on epistemic foundations that hold that knowledge is culturally, historically, and “locally” constructed, a position antithetical to universal or totalizing systems of knowledge that attempt to transcend both history and culture. Thus, rather than upholding fixed, universal, essentialistic, or absolute truths, these multicultural theories of knowledge stress localized, contextual, and embodied features of knowledge (thus the oft-heard phrase that knowledge is a cultural or social construct); as such, they run contra to those Western intellectual traditions like science that hold to some notion of transcendent truth (removed from history and culture) and that, by historical definition, attempt to order and systematize knowledge of the world.

At present, multicultural theories of knowledge, in various guises (included here are postpositivist, post-Enlightenment theories of knowledge),6 are making their way into the study of science, arguing among other things against the unity of knowledge, against coherent abstract logical principles, arguing instead for localized, contextual, and disunified practices. Whereas the introduction of multicultural epistemic frame-works has generated some of the most intellectually exciting scholarship in the social sciences and humanities, it has also garnered negative attention from self-appointed science watchdogs like Paul R. Gross and Norman Levitt, who, in their recent polemic Higher Superstition: The Academic Left and Its Quarrels with Science have derided (and not without some justification) much of the literature that has made its way into science studies.7

The present work offers a narrative that is situated within both of these contrasting positions. It draws heavily from science studies and cultural studies, the true multicultural bête noire, of Gross and Levitt’s Higher Superstition. But while it borrows from some of the most provocative of this literature within the humanities (I refer here to cultural history/cultural study, literary theory, and philosophy of history), it does so to narrate a story that has some meaning for the community of scientists historically and intellectually involved in the project. Whereas the narrative tells of the heroic struggle to unify the branches of knowledge within a positivist theory of knowledge from what students of culture call, sometimes unhappily, an “insider’s” perspective, the story is only possible because it simultaneously embraces a multicultural, postpositivist perspective that gives it enough of a critical distance to make it also an “outsider’s” perspective. Taking the perspective of the scientist or enculturated member through a 359-degree turn, it tries to recover a critical vantage point from which to observe a historical event of some importance. It also attempts to recover what some students of culture have held in disrepute, the genre of the grand or unifying narrative. As the project tries to capture the perspective of the scientists studied herein, all historical measures are taken to retell a story that has meaning to the participants, all of whom searched for coherent, unifying theories. In keeping with some cultural and science studies movements that envision science as a culture, the language, rituals, practices, and cosmologies of the members are also considered in the project. Science is thus “contextualized” as traditional “external” and “internal” are collapsed within a historical perspective that recovers the “language” of science. Scientific content—lost in many of the recent historical attempts to understand science—is an integral component of this story.

Among other things, the present work tells a story of the moment in the intellectual history of the West (one of the cultural categories operant here) when diverging points of view appeared to converge within a unified logical system of thought. It tells a story of a historical event that appeared to fulfill a project at least as deep as the Enlightenment project (or even deeper still) of unifying the branches of knowledge. It tells a story of the emergence, unification, and maturation of the central science of life—biology—within the positivist ordering of knowledge; and it tells a story of the emergence of the central unifying discipline of evolutionary biology (complete with textbooks, rituals, problems, a discursive community, and a collective historical memory to delineate its boundaries). Sustained by a linkage of the autonomous disciplines of knowledge, the proper systematic study of “Man”—his origins and location within a progressive cosmological scheme—became cojoined and reducible through logic to the mechanistic and materialist frameworks of the physical sciences. What effectively emerged was an evolutionary world-view, a cosmology, and a poetic Weltanschauung, fulfilling an intellectual project that began with the very origins of the narrative of science in Western culture.8

The historical event in question took place between the third and fourth decades of the twentieth century during the interwar period. It is recognized by various terms, the most appropriate of which for historians is the “evolutionary synthesis.” Variously—and confusingly—interpreted by evolutionary biologists, historians, and philosophers to the point of engendering some of the most acrimonious debates in contemporary evolutionary biology, it has remained a cornerstone of the history of modern evolutionary thought, grounding contemporary biological theories ranging from sociobiology to exobiology. The story told herein recognizes the contributions of the evolutionary synthesis, and attempts to understand why it has occupied the thoughts of biologists, historians, and philosophers of science. As the story unfolds it also tells of the origin of a group of “architects” and “unifiers,” members of a unifying discipline called evolutionary biology that in turn would form the unifying principle of the modern biological sciences, serving ultimately as the fulcrum of a liberal, progressive, humanistic, and evolutionary worldview.

Although the narrative of Unifying Biology should ideally speak meaningfully to the community of scientists involved in its formation, without prolonged theoretical or methodological discussion, failure to include these features would disengage potential audiences from the humanities. Because the methodology or historiography (literally the writing of history) may be of equal interest to the humanities as the narrative proper, the book is organized so that it will facilitate enough comprehension to provoke discussion across audiences from the sciences to the humanities. Readers might engage relevant parts selectively as they wish. Part 2 (including the narrative of Unifying Biology: The Evolutionary Synthesis and Evolutionary Biology, which has already appeared in print in a somewhat shorter version) can stand alone, or it can be read along with the other parts.9

In addition to chapter 1, the present exegetical opening, which hints at the broader epistemic, political, and existential issues raised by Unifying Biology, I have included several other chapters to set the stage for the narrative for varied audiences. All of these are assembled in part 1, entitled “History, Theory, and Practice.” Readers who are not familiar with the evolutionary synthesis, its importance, and the mass of confusing literature on the subject may benefit by reading chapter 2, “A ‘Moving Target’: Historical Background on the Evolutionary Synthesis,” which includes a review of relevant literature as it traces developments in recent evolution through to the 1980s. Historical and analytical discussion is continued in chapter 3, “Rethinking the Evolutionary Synthesis: Historiographic Questions and Perspectives Explored,” which poses questions of existing approaches, explores alternative modes of historiographic inquiry, and criticizes possible story lines. Chapter 4, entitled “The New Contextualism: Science as Discourse and Culture,” takes readers historically through much of the recent literature in science studies and cultural studies and develops a means for contextualizing the evolutionary synthesis. Among other things, it engages in discussion of the form of contextualist historiography developed for Unifying Biology, so that the theoretical and methodological scaffolding for its narrative construction is revealed. Scientific readers may wish to skip this section, though I make an effort to engage their readership as best I can.

I have also added chapter 6 entitled “Reproblematizing the Evolutionary Synthesis” in part 3 (“Persistent Problems”), which breaks with the constraining narrative format of chapter 5 to respond directly to the potential concerns of readers, to add additional clarification, and to provide pointers for further study into the history of evolution and biology. The “Epilogue” returns to the deeper undergirding themes of Unifying Biology introduced in the exegetical opening. Although it was not my original intention, the present organization does bear close resemblance to the standard scientific paper: abstract, introduction, materials and methods, results, and discussion. Very probably, this is a carryover from a problem-oriented view of history for which existing tools and instruments (in the way of historiography and cultural theory) have been developed and applied. In the conventional manner of the scientific paper, the discussion and conclusions address remaining problems and point to possible areas for further inquiry. This alternative way of envisioning the organization in its entirety may aid some readers, who may be perplexed by the content, tone, and organization of the chapters.

WRITING Unifying Biology

The grand narrative has lost its credibility, regardless of what mode of unification it uses, regardless of whether it is a speculative narrative or a narrative of emancipation.

Jean-François Lyotard, The Post modern Condition

One would be hard-pressed to envision both the history of modern science and extant scientific practice—especially for historical sciences like evolution—without belief in grand narratives, or universalizing stories about the world. Reports of the death, demise, or “loss of credibility” of grand narrative are thus somewhat exaggerated, very possibly limited to those individuals living at the periphery of the text within their “Postmodern Cond...