![]()

PART 1

ARCHITECT OF THEIR LIVES

What is character but the determination of incident?

What is incident but the illustration of character?

—Henry James

![]()

ONE

EXACTLY HOW MUCH A TALE his story was, how much a metaphor for the rise of the American Irish in general, Joe Kennedy himself would never acknowledge. In the middle of his life, when a Boston newspaper referred to him as an “Irishman” one time too many, he exploded: “Goddamn it! I was born in this country! My children were born in this country! What the hell does someone have to do to become an American?” He surrounded himself with tough-talking Boston Irish, yet he had little patience with the easy tears and fusty rhetoric of the stage Irishman who blamed all his woes on discrimination. A self-made, indeed, a self-created man, he was fiercely protective of the individual nature of his accomplishment and had to believe that it was due to temperament, to his own will and philosophy, to what he liked to call “moxie,” and not to the sharp and tragic rejection his people had experienced from the time they first set foot on American soil. Those who knew him best, however, saw Joe Kennedy as Irish to the core—a logical outcome of the undeclared war that went back at least two hundred years before his birth to the day when a woman named Goody Glover was hanged as a witch on Boston Common because she’d knelt in front of a statue of the Blessed Virgin while telling her beads in the “devil’s tongue” of Gaelic.

The saga of the Irish in America—a history Joe Kennedy rarely mentioned but never forgot—was part history and part parable. The first federal census, in 1790, had listed only 44,000 persons of Irish birth, most of them Ulstermen (“Scotch-Irish,” they called themselves) who, as skilled workers and small businessmen, had become outriders for the conquest of the American frontier. Over the next few decades immigration increased, but in 1845 the history of Ireland and America was altered forever when Irish farmers discovered a “blight of unusual character” during the early stages of the potato harvest. The crop had been unreliable for several years, but now freshly dug potatoes turned rotten in hours, decomposing into a gelatinous black ooze with a putrescent smell. Livestock fed on the potatoes died; people hungry enough to eat them became violently ill. As the blight spread, the Crown convened boards of inquiry whose learned men theorized that the disease was perhaps caused by steam emitted from the locomotives recently introduced into Ireland, by sea-gull droppings the farmers used as fertilizer, or even by “mortiferous vapours” rising up from “blind volcanoes” deep in the earth. But if the causes were mysterious (it would later be discovered that the blight had been transmitted by a fungus that traveled to Ireland from America), the effects were clear enough. Over the next ten years, the period of the Great Hunger, a million Irish died and another million left their homeland, most of them heading across the sea.

The only parallels for this exodus were the plagues and persecutions of the Old Testament. Packet ships following the example of the Cunard Lines offered fares as low as twelve dollars between Londonderry or Liverpool and New York or Boston; often the tickets were purchased by absentee English landlords anxious to be rid of their starving peasants. The Irish squeezed onto the “coffin ships,” floating pest houses of typhus and other diseases, and undertook a voyage as close as any white man ever came to experiencing the dread Middle Passage of the African slave trade. As much as 10 percent of a shipload were likely to die at sea. In 1847, the most disastrous year of all, an estimated 40,000, or 20 percent of those who set out from Ireland, perished on the trip. “If crosses and tombs could be erected on water,” wrote a U.S. commissioner for emigration, “the whole route of the emigrant vessels from Europe to America would long since have assumed the appearance of a crowded cemetery.”

Until 1840, Boston had been little more than a debarkation point for immigrants moving on to Canada and the interior of New England. In 1845, in fact, the city’s foremost demographer confidently asserted that there could be no further increase in the city’s population. But over the next ten years, a tidal wave of newcomers—Boston’s harbor master claimed to be able to identify another shipload of them as far away as Deer Island just by the smell—piled off their ships, swarmed into Boston, and stayed, a quarter of a million of them. Called “famine Irish” to distinguish them from their predecessors, they were too poor to pay the tolls and fares that would take them out of the waterlocked city; they packed into the reeking Paddyvilles and Mick Alleys, as many as thirty or forty crowding into one tiny cellar, prey to accident and disease that made their death rate as high as it had been in Ireland at the height of the hunger. By 1850 they comprised a third of the city’s population. Gravid with their sudden weight, Boston was about to give birth to the first American immigrant ghetto.

Construction companies from all over the country sent to Boston for Irish contract laborers, transporting them to new destinations in railway cars with sealed doors and curtains nailed across the windows. Those who stayed behind became coal heavers and longshoremen, “muckers” and “blacklegs” who dug canals and cleared marshes, remaking the face of the city and giving it an opportunity for unparallelled growth and expansion. (When tourists remarked on the beauty of the cobblestones on Beacon Hill some Irishman was sure to remark, “Those aren’t cobblestones, those are Irish hearts.”) Yet they remained a people apart, exempt from New England traditions of transcendental humanism and social uplift which pitied southern Negroes but not their own white slaves. By the 1850s, the infamous NINA—No Irish Need Apply—signs began to appear in Boston, as the antagonisms that culminated in the Know-Nothing Party and other nativist movements reached a dangerous simmer. Boston’s Brahmin elite retreated from the Irish as if from contagion, dividing the city into two cultures, separate and unequal. Mayor Theodore Lyman spoke for those who intended to keep it that way, labeling the Irish “a race that will never be infused with our own, but on the contrary, will always remain distinct and hostile.”

This was the atmosphere that twenty-six-year-old Patrick Kennedy found when he arrived in Boston in 1849. He was the third son of a prosperous farmer; the Kennedys of Dugganstown, New Ross, in County Wexford, had eighty acres on which they grew barley and raised beef, and their county was one of the areas least affected by the famine. Unlike the other immigrants, who were literally fleeing death, Patrick had undertaken the journey to improve his fortunes. He left his parents behind, a brother, James (the oldest son, John, had died in the battle of Vinegar Hill), and a sister, Mary. He would never see them again; they would never see America.

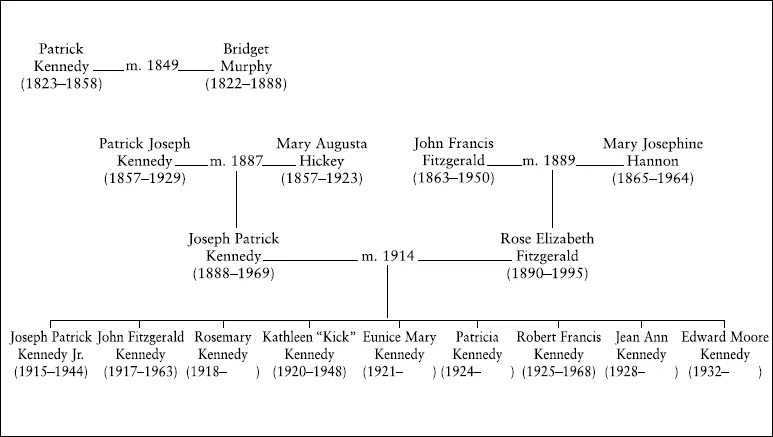

A handsome, muscular man of medium build, with reddish brown hair and bright blue eyes, Kennedy was not alone when he stepped off the Washington Irving at Noddle’s Island, a strip of land in Boston Harbor that eventually became East Boston after Irish labor had joined it to the mainland. On board he had met Bridget Murphy, also a refugee from County Wexford, and begun his courtship at once. They were married on September 26 of the year they arrived, in the Holy Redeemer Church, by Father John Williams, later to become Boston’s archbishop.

The Kennedys went no farther than East Boston, possibly because, like many of their compatriots, they couldn’t afford the two pennies it cost to take the ferry across the bay. Patrick sat with other Irishmen on the piers in the shadows of the Cunard liners hoping a short-handed stevedore could use him, and, along with other newcomers, walked the crooked streets winding up from the docks looking for work in the warren of small shops. After a while he was able to establish himself as a cooper, fashioning yokes and staves for the Conestoga wagons heading west in the great Gold Rush to California and making whiskey barrels destined for the waterfront saloons where the Irish met to exercise their natural sociability and drown their sorrows.

At a time when Americans were beginning to move to cities to escape the smothering traditions of farms and villages, the Irish reaffirmed the conservative values of their recent rural past in the new urban setting. The tenement apartment, like the Irish farm, was a place where the generations stayed together; the family was the primary unit of emotion and survival. As the New World yielded less to their efforts than they had expected, the Irish turned inward to their kin for support, accenting the “clannishness” the Brahmins found so primitive. Like other immigrants who had left one family behind, Patrick and Bridget Kennedy quickly started another—four children in rapid succession, Mary, Margaret, Johanna, and, on January 14, 1858, a son, Patrick Joseph.

Whatever the fanciful tales told back in the Old Country, there were few rags-to-riches stories for this first generation of Irish. The streets of East Boston were not paved with gold. Instead of a material legacy, they left a sweat equity in America for their children and grandchildren to capitalize on. On November 22, 1858, ten months after the birth of his son, Patrick died of cholera, leaving behind no portraits or documents, just a family. He had survived in Boston for nine years, only five less than the life expectancy for an Irishman in America at mid-century. The first Kennedy to arrive in the New World, he was the last to die in anonymity.

HER HUSBAND’S DEATH FORCED Bridget Kennedy to look for a paying job, and she clerked in a notions shop near the ferry building which, through hard saving, in time became hers and the main support for her family. In an era when Irish ambivalence about America was intense—some Irishmen would soon riot against the draft at the same time that others were serving with distinction in campaigns against the Confederacy—Bridget Kennedy had no doubts about her adopted home. Realizing that the boy Patrick Joseph (known in the neighborhood as “Pat’s boy” until they gave him the grownup nickname “P. J.”) was the key to the family’s future, Bridget and her daughters pampered him and tried to keep him out of trouble. For a while he went to a school run by the Sisters of Notre Dame and helped his mother in the shop. But by the time he was a teenager, he was working on the docks as a stevedore. Over the next few years, as his sisters married, P. J. saved his money, looking for a way to solidify his family’s tenuous hold on respectability. Not long after his twenty-second birthday, he heard of a run-down saloon for sale in a dilapidated section on Haymarket Square. With loans from his mother and sisters, he bought the place and went into business for himself.

P. J. Kennedy had the most important qualification of a saloonkeeper: he was a good listener. What he heard from the other side of the bar during the first years he was building his business had less to do with the tragic hopelessness of Ireland than with questions of power in Boston. When the Irish first arrived, the Brahmins, eloquent theorists about democracy, had tried to blunt their impact by statute—attempting to extend the residency requirement for voting from five to twenty-one years. When this maneuver and others like it failed, they had sought to keep the Irish quarantined in shanty towns. But it was this enforced closeness, combining with their Old World heritage of clandestine organization for self defense, that made the Boston Irish political in a way that was unrivaled by any other immigrant group.

Politics for them did not result from abstract theories about representative government or the perfection of human nature; it was a strategy of survival. By the 1870s they had begun to form barroom associations which took over and systematized the chaotic political behavior in the streets. Building on family friendships and neighborhood loyalties, going street by street and ward by ward, they began moving into the local Democratic Party structures, taking them over by sheer numbers and nerve—that “moxie” Joe Kennedy would prize so highly and turning them into something like a parallel government, a “machine” that had to be built because existing civic institutions did not serve their needs for jobs, for protection against unscrupulous landlords, employers, and other social predators. In New York the machine was Tammany; in Boston it was a network of political clubs spread throughout the city’s wards, each with a “boss” bound to his people by a web of mutual loyalty and self-interest, brokering power for himself and his constituents.

The first great boss in Boston was Martin Lomasney, a stubby, cigar-chewing man in a derby whose father had been a tailor in Ireland. Known as the “Mahatma,” Lomasney met immigrants at the wharves and herded them to his headquarters at the West End’s Henricks Club. The deal he offered showed the beautiful simplicity of the machine, a synchronicity of moving parts that made it the political equivalent of perpetual motion. In return for help getting them settled, Lomasney asked only that the newcomers register as Democrats and vote as he told them to. (And for those uncertain about the mechanics of the franchise he had “electoral aids” to help them, the most famous of which was a “fine-tooth comb” with the teeth cut out in a pattern that, when superimposed on a ballot, showed exactly how to vote.) With their votes he got patronage which he used to find them employment. He sold his services effectively: “Is somebody out of a job? We do our best to place him and not necessarily on the public payroll. Does the family run in arrears with the landlord or the butcher? We lend a helping hand. Do the kids need clothing or the mother a doctor? We do what we can, and sure, as the world is run, such things must be done. We keep old friends and make new ones.”

There was a perverse integrity in Lomasney and his system, as muckraking journalist Lincoln Steffens discovered when he came to Boston to do a damning article on the Mahatma and found him far from defensive. “Who do you think you’re kidding?” Lomasney challenged him. “You get paid for muckraking and I get paid for creating what you call the muck.… Look, you walk your side of the street and I’ll walk mine.” The two men ultimately became friends and later on Steffens said that it was Lomasney, more than anyone else, who had made the Boston Irish “players in the game.”

For an ambitious young man like P. J. Kennedy, this game offered excitement as well as rewards. Although just into his twenties, he cut an imposing figure—a large man with a full face, thick red hair, and piercing blue eyes that almost seemed larger than the Teddy Roosevelt glasses. He had already established himself as trustworthy and responsible, “old beyond his realistic years,” as a customer said, and had been successful enough to buy a second tavern across the street from the East Boston Shipyards where he had once worked. Having seen the dangers of drink up close, he was that rarest of Irishmen, a teetotaler, relaxing his rule only on the most festive occasions, when he allowed himself a single shot glass of beer. As the saloons made money, he looked for other opportunities, buying into a partnership in a well-known Boston hotel called the Maverick House, and in 1885 opening his own liquor-importation business, P. J. Kennedy and Company, located at numbers 15 and 17 High Street. His major product was Haig and Haig scotch, which he supplied to some of Boston’s best hotels and restaurants.

Political by nature, he found that politics came naturally to him. In 1884 he had been elected to the Democratic Club of Ward Two. (He publicized both his careers at once, handing out to everybody wood-handled corkscrews inscribed “Compliments of P. J. Kennedy and Co., Importers.”) Because East Boston lacked a strong leader of Lomasney’s stature, he moved rapidly into the ward’s hierarchy. In 1886, the year that children of Irish immigrants first outnumbered those of the native born in Boston, P. J. and his allies took control of the Democratic Committee of Ward Two and he was elected to the State Senate.

At the same time he was choosing a political life, Kennedy began courting Mary Augusta Hickey (“Mame” he called her). A handsome, physically imposing woman (larger than P. J. himself), she was the daughter of James Hickey, a prosperous businessman. Mary Augusta later told her children how she had watched the young legislator passing the parlor window of the Hickey home at 144 Saratoga Street on his morning route, and “set her cap for him.” It was a good match for Kennedy because the Hickey family was more settled and more “comfortable” than his own. One son, John, had graduated from Harvard Medical School, among the first Irishmen to do so. Another son, James Jr., was moving up through the ranks of the Boston police force toward an eventual captaincy. A third, Charles, was a funeral-parlor owner in Brockton, where he also dabbled in politics on the way to becoming the city’s mayor. The Boston Irish community might have considered the Kennedys beneath the Hickeys, but P. J. himself did not. On Thanksgiving Eve, 1887, he and Mary Augusta were married at Sacred Heart Church.

The couple moved into a three-story house at 165 Webster Street. Set on the crest of a hill, its back lawn sloping towards Boston Harbor, its front yard facing the city skyline, No. 165 was one of the most modest dwellings on a block which was rapidly becoming known as the Beacon Street of the Irish community. The following year, P. J.’s mother, Bridget, died in her home at 25 Borden Street at the age of sixty-seven. She had lived long enough to see “Pat’s boy” establish himself in the new world where she had struggled to survive. She had also lived long enough to see his first child, Joseph, born into it on September 6, 1888.

That year was significant for P. J. in another way: the party organization chose him to go to the Democratic National Convention and give a seconding speech for Grover Cleveland. It was a year when Boston’s Irish elected their first mayor, Hugh O’Brien, and were climbing the greasy pole of political ambition with a vengeance. But while enjoying the official success of their assault, they had also gotten a feel for the severity of the struggle ahead. Evicted from City Hall, Boston’s Brahmins had retreated to their Back Bay brownstones, grasping the levers of economic power all the more tightly and drawing social lines with a sharper edge. The message was clear: the Irish could be policemen, civil servants, settlement-house workers, even mayors; they could have the thankless task of assimilating and controlling a new wave of Catholic immigrants from lands where English was a foreign language. But they could not expect acceptance or a partnership in the complex arrangements by which ultimate social power was exercised.

During three terms in the Massachusetts Senate, P. J. did not distinguish himself as a particularly innovative or energetic legislator. In the entire 1892 session, for instance, he introduced only two bills—one mandating the clerk to supply daily magazines to the legislators and the other to put two more men onto the payroll o...