This is a test

- 504 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book looks at Ireland's problems from geographic and environmental perspectives, placing them within their regional, national, and international context. It is invaluable to students, decision-makers, and all those interested in the current situation in Ireland and its future.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Ireland by R. W. G. Carter,A. J. Parker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economía & Historia económica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 INTRODUCTION

Bill Carter and Tony Parker

Images of Ireland abound. The Ireland of the tourist brochure is an idyllic landscape populated by friendly people with a thousand welcomes. The Ireland of the media is all too often one of divided communities, political intransigence, terrorism and crime. Industrial Ireland is a European base, with generous tax concessions, low overheads, a large pool of unemployed labour and factories that can be abandoned without conscience when times are hard. Agricultural Ireland is green fields and dairy cows, a bottomless pit for European Community funds. While such images are not wholly unrepresentative, they do reflect many complex and changing facets that comprise Modem Ireland.

The essential aim of this book is to explore the dynamic spatial patterns that form the physical and social environments of Ireland. Of particular interest are Irish resources, ranging from people and their skills, to lands and minerals; the ways in which these resources are being allocated or used, and the conflicts that arise during these processes. Over the last 40 years, Ireland has undergone major changes in social and economic conditions. By and large these have been achieved at the expense of environmental quality. However, we are entering an era when the need to replace the old concepts of continual economic growth with ideas of 'sustainable economics’, in which pragmatic economics, social justice and environmental well-being are cornerstones. In many ways such a strategy finds the geographer with his/her eclectic skills, embracing physical, biological, social, economic and cultural systems, exceptionally well-placed to determine national and international futures. Whether geographers will grasp this nettle, or even have the confidence to try is another matter!

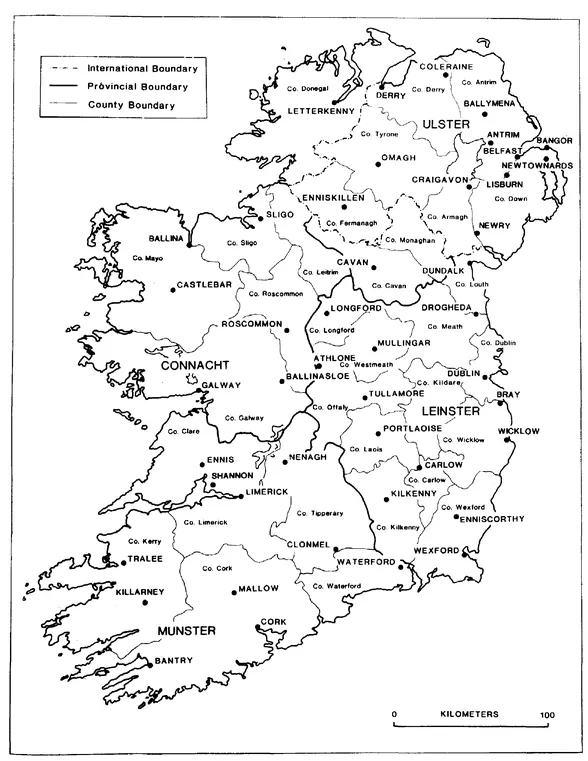

Figure 1. Ireland

As most people are aware, Ireland composes two states, the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland (Figure 1). The former is an autonomous republican democracy, while the latter is part of the United Kingdom, a monarchial democracy, governed from Westminster. While details of events leading up to partition in 1922 are well recorded elsewhere, the consequences of this action have had a fundamental impact on Irish geography ever since. The divergence of political systems, the dichotomy of approach to common geographical problems (like industrialisation, rural deprivation and land reform) has added an additional veneer to already complex circumstances. In many ways the presence of die UK's only land border - 410 km long - is both inflammatory and intimidatory, yet arguably provides the economic stimulus along an otherwise deprived and marginal zone. It is a paradox that many of the people who condemn and ignore the border, are those who benefit most, in financial terms, from its presence. Whether one is dealing with acts of political terrorism or doing the family shopping, the border is a prominent feature in the human geography of Ireland.

The political border between the states is a geographical nonsense, based on nothing more than Anglo-Norman county lines, often cutting roads, communities, farms and even buildings. There are many other, clearer spatial contrasts. Perhaps the most acute is the division between the relatively affluent east and relatively poor west. By an accident of geography, the east of Ireland, both in the Republic and Northern Ireland is endowed preferentially with a less extreme climate, better soils and high biological diversity and productivity. Also the east is nearer the dominant transport routes to Britain and Europe, and has developed the largest urban centres - Dublin and Belfast - with the more sophisticated economic, cultural and social infrastructures. As a result there are strong east to west falling gradients in terms of disposable income, educational opportunity, employment, economic prosperity and resource marginality. Such gradients are often self-reinforcing as people move towards the urban east to avail themselves of perceived advantages. Attempts to stem these migrations, especially in the Republic of Ireland, for reasons ranging from linguistic preservation to the mitigation of urban over-crowding, have met with variable success.

As will become clear in the various chapters of this book, Ireland is an island under stress. These stresses emanate not only from religious, cultural and political divides, but also from a tendency to 'overreach' in environmental terms in order to meet economic goals. All too often political expediency has determined policy, leaving confused and even chaotic situations. For example, there is no coherent energy policy (although Ireland is not alone in this deficiency), rather there has been a series of tactics, in which various options have been promoted and then discarded over the last 30 years. Environmental stresses in Ireland have combined with social ills to reduce the quality, if not the quantity, of life. Thus Dublin suffers the last chronic urban pollution in Europe, again resulting from inadequate long-term policy in terms of housing, fuel supply and service provision. Deprived and stressed communities are prone to react. This reaction may be confined to specific cohorts, for example unemployed adolescents, but nevertheless is usually associated with general social and environmental malaises. Thus urban Dublin and Belfast, and even some rural areas, have witnessed staggering increases in crime, self-abuse (drug taking, alcoholism), community denigration (littering, vandalism, intimidation) and political radicalism.

As well as spatial division and gradation, one must add social discrimination, founded not only on value-based social stratification, religious beliefs or social class, but also on newer schisms of educational and vocational mobility, psychological attainment and welfare provision. Added together these spatial and social dimensions constitute an extremely complex human ecology of Ireland.

Perhaps the most significant date in Irish history since 1922 is 1973, when Ireland, both the Republic and Northern Ireland, was accepted as a member of the European Economic Community (now shortened to European Community (EC)). Reasons for joining the Community were twofold. First there was a hedonism to be part of a common economy in which trade and personal mobility barriers were negligible, and second, there was a need to retain important traditional markets (mainly that between the Republic and the UK). So far both parts of Ireland have fared well from EC membership, to some extent living vicariously on the successes of the core member states (West Germany, France and Britain). Differential application of EC tariffs and intervention prices across the border have tended to encourage smuggling - for example it is thought about 90,000 head of Northern Irish cattle crossed the border illegally in 1986 to qualify for the higher beef tariffs in the Republic. The very fact that EC affairs in Northern Ireland have to be channelled through London is also a handicap and may have disadvantaged some economic sectors in the Province.

The EC has moved, through the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP), to protect Irish Farming and Fisheries, while membership has opened new markets, not only for agricultural goods, loosening the economic ties with Great Britain. Much of Western Ireland has benefitted from the Regional Development fund, which has financed many infrastructural improvements, from new harbours and roads to the replacement of fishing boats and the promotion of tourism. All of Ireland is considered 'deprived' in EC terms, along with southern Italy, Greece and parts of Spain, Portugal and France. Specific EC enhancement projects, like STAR, are aimed at improvement of facilities and services, and at creating opportunities for development, especially in the creation and encouragement of small and medium sized enterprises.

Yet the style of job creation and provision is markedly different in the two parts of Ireland despite broadly similar objectives. Northern Ireland has, until recently, concentrated on large, often prestige, investments, often coercing British 'mainland' firms to open new plants. Much of the new 1960s industry has now closed, only one man-made fibre plant, Du Pont in Londonderry, remains out of six, and there have been some spectacular collapses including heavy investment in two American projects in cars (De Lorean) and aircraft (Lear Fan). The investment per job is high (over £25,000) and only 25% of those created provide long-term secure employment. The industrial geography of Northern Ireland is largely one of chaos and trauma, with often nebulous criteria dictating decisions on location and funding. Meanwhile, the Republic of Ireland has adapted a more flexible, and to the annoyance of its northern counterparts, a less bureaucratic and more generous strategy, enabling them to attract more jobs over a wider range of skills and locations. There have been failures here as well, but by-and-large they have been fewer and less well publicised.

In addition to direct benefits, EC membership has opened labour, education and leisure to wider markets, and fostered development of new transport links in air and shipping. The Republic of Ireland, in particular, has achieved a new assertiveness within Europe, matched, to some extent, by an evolving identity and a new sense of place, all qualities worthy of study by geographers.

Simultaneously, Ireland has become pivotal to non-EC countries wishing to enter or expand in Europe. Most significantly, Ireland is often closer, in all senses (time, distance and culture), to eastern North America than to many parts of the European Community, thus making the country attractive for investment.

The detriments of belonging to a pan-European community are perhaps more subtle than the benefits. The economic map of Europe has been redrawn, many would welcome redrafting of the political one, with Ireland retaining only a nominal representation in a strengthened Euopean Parliament. Ireland is peripheral to Europe's core, and in the case of Northern Ireland, denied direct access. Such peripherality has led to a 'deskilling' of Ireland, both by the gravitation of the better trained towards the European 'core' (assisted by the abolition of work permits within the EC), and the reduced demand for skilled labour in what is becoming a 'branch plant' economy. It could be argued that Europe has a vested interest in maintaining this status quo, preferring to balance the outflow of talent with inflow of supporting funds to develop the infrastructure, but not the economic base.

The late-twentieth century finds Ireland a much altered country. Demographic and social turbulence is not new, but significant new trends have emerged. The burgeoning population, one in three is under twenty, coupled to a reawakening of nationalistic and religious beliefs, has led to a retrenchment of distinctive values, and a reborn opposition to politically scripted social change.

Towns, villages, families and individuals have undergone upheavals in lifestyle within the last two generations. Towns and villages have changed functions and the waxing and waning of regional urban centres has led to changes throughout Ireland. The building of new roads, faster trains, and even the establishment of an internal air service, has reinforced the dominance of a few major centres, at the expense of small towns. Some survive by metamorphosis, switching from small district centres to commuter centres, including Antrim, Newtownards and Lisburn around Belfast, and Bray, Lexlip and Clondalkin around Dublin. Others towns have developed as tourist centres including Wexford, Sligo, Killarney and Enniskillen. Many urban centres continue to survive with a mixture of small industry, service economies and visitors.

Rural Ireland presents the greatest paradox. It is promoted as a major attraction for all the qualities - relaxing, old-fashioned, quiet - that make it hard to live in, especially for the young. The decline of the traditional nuclear family, most noticeable since 1950, has presaged all manner of social problems, from a breakdown in kinship to a neglect of the elderly. Rural Ireland is dominated by farmers; some are very wealthy - rural Northern Ireland boasts more BMWs than any other comparable area of the UK - but many are still poor, particularly those farming marginal land, where profitable years are less than one in three. Today, the 'forty shades of green' tend to reflect the the level of fertiliser application, rather than natural variations in the agricultural landscape. A journey from the outskirts of Dublin to north Co. Donegal, or Belfast to west Tyrone, crosses one of the most abrupt human gradients in Europe. At the extremes, rural life is sustained only by state financial support and in some cases 'money from America'.

The late twentieth century transformation of Irish society and landscape owes as much to the surge of economic activity in the 1960s and early 1970s as it does to the slump in the late 1970s and 1980s. Attempts to stave-off economic disaster only result in the penalty of environmental demurrage at a later date. The tactic of encouraging economic growth and exports will, for example, often be at the expense of laxity in pollution abatement. Too much Irish waste is just dumped into the sea, rivers, onto land or into the air. Such tension may manifest itself in the setting of environmental standards which reflect the judgement of society as to what is an 'acceptable' level of environmental degradation commensurate with particular economic or social benefits. Although such standards (often imposed through EC directives) have their origins in dosage response relationships, they are usually set at a politically expedient level based on the consensus of the electorate. (A complication in this statement has arisen over the release by Britain of nuclear waste into the Irish Sea, provoking an international disagreement between the two countries.)

It is interesting that there is no effective 'Green' political party in Ireland, especially in the Republic of Ireland where the Proportional Representation electoral system might allow participation in government. While there is undoubtedly a 'green conscience' among many elected representatives, it is not particularly evident at party political level. The decision in 1987 to dismantle the State planning and conservation service, An Foras Forbartha, is symptomatic of this total lack of commitment, as well as an act to be deplored. It may be that the style of politics, often of the 'pork-barrel' variety in the Republic, and secular in Northern Ireland, mitigate against an effective environmental grouping. Notwithstanding this, it is clear from interest and action that the Irish population is becoming environmentally sensitive and this trend may give rise to an effective lobby in due course.

Ireland, both north and south, is a land in a state of rapid change, against a backdrop of long-term conservatism and tradition. The framework of the EC with a common market emerging in just four years time is increasingly dominant in Irish affairs, and the problems faced by the island are similar to those in other peripheral lands of Europe and elsewhere. This book is written by professional geographers and environmental scientists who share an affection for Ireland and who wish to focus attention upon the many-faceted aspects of Ireland today and in so doing, if possible, help navigate a passage towards the potentially calmer waters of the twenty-first century.

2 EUROPEAN ECONOMIC POLICIES AND IRELAND

Frank J. Convery

In this chapter, it is assumed that 'European Economic Policy' comprises an amalgam of economy-related financial and institutional policies applied by the European Community (EC) to Ireland, the United Kingdom and Denmark since their acceptance for membership in 1973. The purpose of this chapter is to trace th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- CONTRIBUTORS

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- 1 INTRODUCTION

- 2 EUROPEAN ECONOMIC POLICIES AND IRELAND

- 3 PARTITION, POLITICS AND SOCIAL CONFLICT

- 4 IRISH POPULATION PROBLEMS

- 5 CRIME IN GEOGRAPHICAL PERSPECTIVE

- 6 THE HISTORICAL LEGACY IN MODERN IRELAND

- 7 THE PROBLEMS OF RURAL IRELAND

- 8 AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT

- 9 THE NEW INDUSTRIALISATION OF IRELAND

- 10 THE CHANGING NATURE OF IRISH RETAILING

- 11 TRANSPORTATION

- 12 PATTERNS IN IRISH TOURISM

- 13 IRISH ENERGY: PROBLEMS AND PROSPECTS

- 14 WATER RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

- 15 RESOURCES AND MANAGEMENT OF IRISH COASTAL WATERS AND ADJACENT COASTS

- 16 AIR POLLUTION PROBLEMS IN IRELAND

- 17 REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT STRATEGIES

- INDEX