![]()

CHAPTER 1

500 YEARS AFTER LUTHER’S 95 THESES: A CATHOLIC PERSPECTIVE

ORLANDO O. ESPÍN

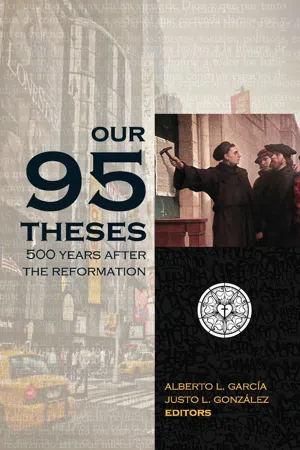

IN 2017, THE UNIVERSAL (WORLD-WIDE) CHURCH will commemorate and celebrate the fifth centennial of an event with enormous consequences for the history of Christianity, even though at the very moment — when it took place in 1517— it seemed to be no more than a bold invitation made by an Augustinian monk, who was a university professor in a very small German town, to his students and colleagues at the same university. This invitation to a theological debate questioned the presuppositions that praised the sale of indulgences. With these ninety-five theses presented for debate, Martin Luther boldly carved for time immemorial his name in the annals of church history.

My contribution to this ecumenical project is consciously made as a Latino who is also a theologian and Catholic.2 One has to be oblivious and ignorant concerning history and theology in order not to take note of the importance of Luther, and his witness at a time that was very much needed for the church. The reader should not expect, therefore, an anti-Lutheran diatribe (because he will not find it here nor in any other place under my name) nor should the reader expect canonization of the Augustinian monk of Wittenberg under my authorship (because not even Luther would be convinced by this). The reader should not expect either the one and only Catholic perspective, but rather barely one perspective.

Since the second half of the twentieth century, positive relationships between Catholics and Lutherans, as well as between Catholics and many other Christians, have developed in ways impossible to imagine during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This is specially so among U.S. Latino and Latina theologians (Catholics and non-Catholic alike) through their fraternal ecumenical relationships, personal friendships, and professional collaborations. They have and continue to be a living example for our respective denominations: U.S. Latino and Latina theology was born respectful of ecumenical endeavors, and continues even more so to reflect this spirit. My humble contribution to this book is offered within this framework of a continuing Latino ecumenical dialogue.

1. Martin Luther was Catholic, and it can be historically ascertained that he believed that the reformation movement he initiated was never directed against Catholicism, but rather in favor of it, in order to correct the doctrinal abuses and the moral corruption that were evidently present in the Church of his time. For Luther, the Church was the one that he knew and in which he was baptized and ordained. If the Augsburg Confession, that Melanchthon wrote and edited with the full consent and collaboration of Luther, reflects the mature reformation leader’s posture, then there is no doubt that Luther’s theology was Catholic. A reading of the Augsburg Confession allows us to understand also how, in 1999, the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification, could be signed and accepted by Lutherans and Catholics alike, and later also by Methodists, affirming thus through this document that what both communities affirm concerning justification is complementary, rather than mutually exclusive; and, even more importantly, that what Lutherans and Catholics believe and share in a life together concerning justification by faith is more fundamental than the possible and diverse ways of expressing it.

There is no doubt that Luther was a child of his times, as well as heir to the theological traditions of his teachers and community. As an Augustinian hermit, Luther was formed and educated under a very specific theology (mainly Augustinian) and under a particular spirituality (in his case one that was molded by the thinking and religiosity of the Augustinian Johann von Staupitz). The Augustinian heritage that shaped Martin Luther was indispensable in understanding his theology and thought. That heritage insisted, among many other things also found in the writings of the reformer, that the Scriptures are the center of the spiritual life and of theological reflection; not for personal consolation or satisfaction, but rather for the benefit of the entire ecclesial community. The Bible did not belong to “only one,” but rather to “everyone”. I am not suggesting here that all that the teacher of Wittenberg did was to present or proclaim only what he had received from Augustine. What I am saying is that without his Augustinian heritage, Luther would have not possessed many of the tools with which he was able to create and reflect.

Luther did not invent the wheel, but rather was able to point out to his contemporaries that the wheel was indeed round. If we were to analyze Luther’s theology point by point (especially by reading the Augsburg Confession or some of his other theological writings), we should discover how truly Catholic was this great reformer of the church. To set Luther today against Catholicism is to falsify his role as a reformer.

Why did Rome, then, excommunicate him? For some (including the popes of this period and many of their bureaucratic curia), Luther represented a defiant posture against their authority as well as the power of the ecclesiastical institution and of those benefited by the same. Those who hold power have never liked to be told that they have erred or lied. Instead of listening to Luther’s requests for dialogue, it was easier for some popes, bishops, theologians and bureaucrats to demand that he retract and submit to authority, and thus to stop asking embarrassing questions that they did not wish to answer. They demanded he abstain from comments that may have seemed irreverent to those who ostentatiously held (and profited from) ecclesiastical power. Unfortunately, in the sixteenth century as well as today, there are Christians (Catholics and non-Catholics alike) who confuse their customs, rites, their biblical interpretations or doctrines, and their ecclesiastical norms with the revelation of God. They do not wish to be shown that the wheel is indeed round, especially when it threatens their power, authority, prestige, or security.

In sixteenth century Catholicism, ecclesiastical laws and customs were very frequently confused with God’s revelation. At the beginning of the sixteenth century, was there a need for a profound renewal (reformation!) of Catholicism? There is no doubt that Martin Luther ignited the beginnings of a reformation within Catholicism for the sake of its renewal. He was not the only reformer, but his impact is historically unquestionable. Luther was not the founder, nor did he wish to be the founder of a new church or denomination. He began a reformation movement within the Catholic Church, and always believed that this was the church to which he belonged.

As a Catholic and as a theologian, I do not believe that anyone could sincerely say today that Luther was not that providential “cure” that in fact launched the reformation process so needed in the Catholic Church since the beginning of the sixteenth century, recognizing his fidelity to what he understood to be the Gospel and the Church. Luther’s 95 theses (which obviously do not represent his entire theological and reformation trajectory) emphatically pinpointed the need for serious discussions of some of the practices and doctrinal presuppositions which were very popular, but profoundly questionable in the Catholicism of his day; most notably, the sale of indulgences grounded in theological assertions that had no foundation or merit.

The majority of the 95 theses were an invitation to debate and to question the validity of indulgences and the arguments offered in their support by those preachers who benefited from them. Unfortunately, for many (Catholics or not) it has been far easier to reduce the contents of the theses to the theme of the sale of indulgences, as if this were the only urgent theme in Luther’s thought and reformation proposal. But in fact, among the 95 Theses we may single out some that go beyond the area of indulgences and which are extraordinarily important, for they touch at the very heart of the gospel. Consequently, they demand the attention of Christians of every time and place. For example, we may make specific reference to theses 43 and 45:

(43) “Christians are to be taught that he who gives to the poor or lends to the needy does a better deed than he who buys indulgences.”

(45) “Christians are to be taught that he who sees a needy man and passes by, yet gives his money for indulgences, does not buy papal indulgences but God’s wrath.”

These theses, as well as others, lead me to think that today it is perhaps not the buying of indulgences, but rather other activities and attitudes that give a false sense of security or consolation to the people in our contemporary context (for example: attending church services on Sunday; being supremely faithful to all the utterances made by priests, pastors, bishops, or popes; being extremely faithful in observing canonical law or any other kind of exigencies and external norms; by committing to memory hundreds of biblical verses; by demanding to give a tithe or any kind of offerings; insisting that one belong to this denomination, but not that one; that we dress this way, but not in this other way; that we accept this or that biblical interpretation with no other foundation than the authority of the person who is proposing such meaning; or to participate in a particular type of worship service; and the list goes on and on). Such “buying of indulgences” offers consolation and security to people just as it did to Luther in the sixteenth century, whether bought with good intentions or not. In fact, as Luther so aptly already demonstrated, they ignore or obscure the gospel.

It is certainly true that the great majority of the 95 theses have to do with the abuse of the selling of indulgences: their use and abuse, explanations and manipulations concerning their benefits at the beginning of the sixteenth century. But they have much to say to Christians today who deceive themselves, pretending that there are roads to salvation that do not involve our compassion to the most needy and vulnerable as an irreducible and non-negotiable premise. No one nor anything, no matter what how good or holy, may take the place of a real and effective compassion, for God is compassion. Martin Luther was not the only one who demanded a reformation, but without his resounding prophetic cry, only God knows what would have been the course of Christianity to this day.

2. Historically speaking, it is crucial to understand that the “Reformation” was plural — it cannot be understood otherwise! Within the movement there were many reformation proposals, and these often confronted each other, and not always with understanding or agreement among themselves. There were reformers who remained in communion with Rome, even while criticizing her severely, and there were other reformers who abandoned that communion. The prophetic call to reform the church did not always lead to a schism, even though conscience demanded that action from many.

It would also be correct to add that the “Counter-Reformation,” historically speaking, also took place in the plural, nor did it have as its only purpose the self-preservation of Rome. All, unfortunately, fought and opposed one another in their proposed reformation programs that did not always coincide. Perhaps it would be easy now, five hundred years later, to question the sincerity of those who offered different perspectives from those that we deem correct. But in the sixteenth century it was not very difficult to wish for a reformation: the most difficult was to risk which reformation to embrace, without betraying one’s conscience.

As a Catholic, I am fully cognizant that during the sixteenth century, the reformation movement flared up because it was much needed for the church. Without a doubt, one could not have expected the Roman bishops to initiate such changes since they, along with their bureaucratic clergy, were the main protagonists of corruption in the church. Although we have to recognize the political and financial interests which not were an integral part of Rome, they nevertheless were beneficiaries of the existing ecclesiastical corruption. Religious ignorance, moral corruption and the usurpation of the place of revelation by human customs, doctrinal interpretations, and ecc...