![]()

Part One

Loss of hope

![]()

1

A world in transition

Writing in the early 1950s, Austro-Hungarian intellectual, educator and socialist Karl Polanyi (1886–1964) described the period as ‘an age of unprecedented transition’ requiring ‘all the orientation that history can provide if we are to find our bearings’.1 These words describe even more accurately our contemporary period than they did the period in which they were written. For, to borrow Gareth Dale’s pithy summation of where we find ourselves as ‘liberal-civilisational disintegration’,2 today’s world is displaying ever more severe strains of multiple and reinforcing dislocations that are, indeed, unprecedented. The 2020 coronavirus pandemic highlighted this for many people, shattering a belief in society’s stability and progress. While some speak of the contemporary period at the beginning of the twenty-first century as an ‘interregnum’,3 arguably we have far less sense of where we may be transitioning than had those reading Polanyi’s words when they were written. Or, to put it more accurately, the world of the early 1950s was settling into a contested landscape of East versus West that was to shape the following forty years. This was unsettling, and it grew particularly scary as nuclear weapons added a terrifying potential to the standoff shaping the world at that time. But, as it settled down, it offered categories that made sense to most of the forces shaping and contesting the world order.

Our times are very different. Some see similarities with the breakdown of the liberal order in the last decade of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth. However, as filmmaker David Attenborough put it so starkly when addressing the UN climate summit in Katowice, Poland, in December 2018: ‘Right now, we are facing a man-made disaster of global scale, our greatest threat in thousands of years. If we don’t take action the collapse of our civilisations and the extinction of much of the natural world is on the horizon.’ This is the enormous threat that distinguishes our era from any previous one and adds hugely to an acute sense of disorientation and uncertainty about the future. But, while it is the most grave, it is far from being the only source of disorientation and uncertainty. The two chapters that form Part One examine the loss of hope that characterizes our period of human history. This chapter identifies the multiple and overlapping dislocations that contribute to making it, in the words of Yuval Noah Harari, ‘an age of bewilderment’. The following chapter examines how the crisis is being interpreted with a central focus on the threats to our liberal order and the rise of the ‘new populism’. For, a major part of our disorientation lies, as Harari puts it, in the fact that ‘the old stories have collapsed, and no new story has emerged so far to replace them’.4 Constructing a new story, adequate to the multiple dislocations we face and offering an orientation about how to lay the foundations of a new society adequate to overcoming the system breakdown that currently dominates, is the objective of this book.

As well as outlining the plan of this book, this chapter undertakes two tasks. Firstly, it seeks to identify the nature, scale and interrelationship of the many dislocations that are shaking up our world and disorienting our worldview. The core of the argument here is that we are facing a multifaceted breakdown of our society beyond anything humanity has faced before. This can be seen as constituting the ‘unprecedented transition’ mentioned in the chapter’s opening. The chapter then goes on to examine where we can discover the orientation from history to help us find our bearings. We need to remember that the social democratic era that followed the Second World War took its orientation from the works of John Maynard Keynes since he provided the theoretical understanding of how the state should correct market failures to ensure full employment. The neoliberal era that replaced it found its orientation in the very different theoretical claims of Friedrich Hayek who feared state involvement as an infringement of individual liberties and saw state interference in the functioning of the economy as harmful to society. As neoliberalism collapses, no clear orientation has yet emerged to offer a broad theoretical grounding in a new understanding of the roles of the state, the private market and civil society, and how they interrelate. The central argument of this book is that the oeuvre of Karl Polanyi offers the essential elements of the theoretical grounding so badly needed. ‘Polanyi invites us to step outside the box of formal models of market transactions to explore the real needs of real people and the variety of institutional arrangements that can satisfy them,’ writes his daughter, Kari Polanyi Levitt.5 This opening chapter offers a brief introduction before drawing extensively on his work in subsequent chapters.

System breakdown

Writing about the 2019 Davos get together of the world’s powerful, Guardian columnist Aditya Chakrabortty reports on a survey of a thousand bosses, money men and ‘Davos decision-makers’ in which the majority confess to mounting anxieties about ‘populist and nativist agendas’ and ‘public anger against elites’, identifying two shifting tectonic plates, climate change and ‘increasing polarization of societies’.6 In contrast to these anxieties, Dutch author Rutger Bregman in his bestselling Utopia for Realists? sees a ‘world of plenty’. He reports how technologies are transforming our healthcare, how billions are being lifted out of poverty, how malnutrition, child mortality and maternal deaths have been hugely reduced, how common diseases are being eradicated, how levels of education and average IQ are constantly improving, and how crime rates are falling in the developed world. Even Bregman, who believes we’ve never had it so good, acknowledges that most people in developed countries believe their children will be worse off than their parents.7 There is therefore a techno-optimism that gives some people grounds for a more positive view of the future though this cannot avoid the widespread subjective sense of malaise. The discussion here is structured around six key features of our contemporary global situation to marshal evidence about what sort of future we face. These are the unravelling of our social model, the erosion of political representation, the migration crisis, the dark side of technology, climate change and biodiversity loss, and a widespread sense of personal impotence.8 For many, the loss of hope is very real.

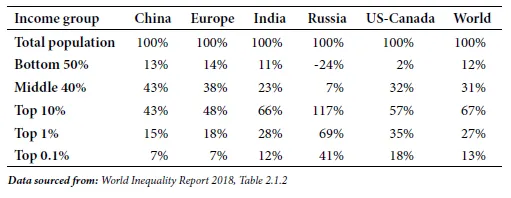

Social model unravelling: it was largely social issues that, at the advent of industrial society in the nineteenth century, mobilized the discontented and exploited to organize and demand better conditions. This they did both through reforms within the dominant system and through revolutionary change to transform that system. These included conditions of employment, levels of pay, housing, health and education, and inequalities of power and wealth. These struggles in the nineteenth century laid the foundations for a socialist movement that, in different forms, won major advances on all these social issues throughout much of the twentieth century. This laid the foundations for decades of progress that underpinned a secure sense that each generation would enjoy better material conditions than their parents. However, the period since the late 1970s has seen this model progressively unravel to the point that a growing sense of vulnerability in people’s material conditions fuels a sense of insecurity about the future,9 a sense greatly enhanced by the Covid-19 crisis. In the 1980s it became common to speak of the end of the Third World as neoliberal recipes for economic and social development spread thereby integrating developing countries in global flows of trade and finance.10 The end of the Second World (the communist world) is dated from the collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the subsequent demise of the Soviet Union. Can we now speak of the collapse of what used to be called the First World, the world’s bloc of developed countries? A common characteristic is that the gains of growth go disproportionately to the very top of the class structure as shown in Table 1.1. The symptoms of this collapse constitute a long list: secular stagnation in many Western economies as economic growth falters, the surge in inequality, the systematic reduction of the protections offered by the welfare state, a growing housing crisis as prices and rents become unaffordable for many, post-industrialization leaving many regions of heavy industry devastated, and the decline in the value of academic qualifications to access secure and well-paid employment.11 While these processes happen in different ways and at different rhythms in different countries and regions, it is now clear that they constitute deep-rooted tendencies in contemporary societies. As Edward Luce has written:

Since the late 1970s, Western governments of right and left have been privatising risk. To one degree or another – most sharply in the US and the UK – societies are creeping back to the days before social insurance. What was once underwritten by government and employers has been shifted to the individual. When people hit the buffers, they knew there were funds to ride them over. Those guarantees have been relentlessly whittled down.12

Table 1.1 Share of global growth captured by income groups, 1980–2016

Erosion of political representation: in being the main agents identified with these tendencies, Western governments are themselves largely responsible for a backlash against liberal politics that has emerged over decades. It has now reached a point that threatens the very foundations of the liberal order. This is a second great system breakdown, linked to but distinctive from the first. The process has long been analysed, though the implications of the attrition of parties as they retreated from the mobilization of citizens to become more technocratic machines to administer states seemed to have little impact on how politics and politicians functioned.13 As the centre-right and the centre-left moved to a politics of implementing neoliberalism14 through privatization, marketization and the liberalization of controls on financial, commercial and labour flows, it resulted in ‘a demobilization along the broadest possible front of the entire post-war machinery of democratic participation and redistribution. It all took place slowly but steadily, developing into a new normal state of affairs.’15 Even as new-right parties entered government in a number of European countries, the gravity of the threat to the liberal order did not seem to register with many. Yet, as Jan Zielonka recognizes, the ‘counter-revolutionary insurgents’, as he calls the new-right movements, want to replace the elites who have presided over the post-1989 liberal order in Europe, and he acknowledges their appeal: ‘They set the tone of the political discourse and establish which issues are debated; they give voice to people’s anxieties and expose liberal flaws; they arouse the politics of fear, acrimony, and vengeance.’16 And he fears that ‘the counter-revolution will not just stop at correcting liberals’ mistakes; it will go further by destroying many institutions without which democracy cannot function and capitalism becomes predatory.’17 And, as evidence from beyond Europe shows – the United States, Turkey, the Philippines, India and Brazil – the phenomenon is global.

Blaming the outsider: the third great system breakdown relates to immigration. It is clear from the discourse of Donald Trump, Victor Orban, Marine Le Pen, Matteo Salvini, Geert Wilders and some proponents of Brexit that fears about immigration are consolidating a base of support for the new-right and endangering social values of tolerance and diversity that underpin a liberal order. The dramatic images in 2015 of waves of immigrants fleeing violence in countries like Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan and seeking out safety, particularly in Germany, seemed to mark a watershed in public consciousness and played a role in the emergence of the Alternativ fur Deutschland as German’s main opposition party. However, framing immigration in the language of crisis creates very misleading impressions since it both exaggerates the scale of migration and reduces the complexities involved, thereby making it difficult to find humanitarian solutions. Furthermore, it focuses public attention on abstract numbers rather than on the human tragedies of those involved.18 Instead of solutions, more and more countries are reducing their national quotas for the resettlement of refugees and asylum seekers, delivering their fate into the hands of people traffickers or forcing them into overcrowded and insanitary camps. In an essay written just before he died, the sociologist Zygmunt Bauman drew attention to the consequences of the climate of mutual mistrust, suspicion and competition that is emerging in this context: ‘In such a climate the germs of communal spirit and mutual help suffocate, wilt and fade (if their buds have not already been forcibly nipped out)’ and the possibilities for concerted actions of solidarity in the common interest lose their value and grow dimmer,19 vividly illustrated by the difficulties of coordinating international responses during the coronavirus pandemic. In this context, promoting a culture of dialogue will require nothing short of ‘another cultural revolution’, he writes.20 Debates about racial difference are nothing new in Europe. Indeed, in parts of medieval and early modern Europe, rulers welcomed refugees and saw them as an asset.21 By the nineteenth century, however, spurious scientific theories justified a hierarchical ordering of peoples on racial grounds; these were discredited and after the Second World War gave way to debates based more on cultural and religious differences, often with sharply racist overtones. These issues, therefore, have never been easy ones but they are clearly becoming much more divisive. The system breakdown being threatened by the emerging standoff is highlighted by Harari: ‘If Greeks and Germans cannot agree on a common destiny, and if 500 million affluent Europeans cannot absorb a few million impoverished refugees, what chances do humans have of overcoming the far deeper conflicts that beset our global civilization?’22

Technology’s dark sides: identifying technology as a symptom of system breakdown runs counter to the techno-optimism that characterizes our technological civilization. After all, people widely credit technology with making our lives easier, better and longer. Our governments invest large sums of money in technological research as a means of solving many of the great problems that beset us, not least climate change. Yet, while technologies are presented to us as inherently emancipatory, James Bridle reminds us that our lives are utterly enmeshed in technological systems that shape how we act and think:

Our technologies are complicit in the greatest challenges we face today: an out-of-control economic system that immiserates many and continues to widen the gap between rich and poor; the collapse of political and societal consensus across the globe resulting in increasing nationalisms, social divisions, ethnic conflicts and shadow wars; and a warming climate, which existentially threatens us all.23

In case this seems an exaggeration, let’s take the exam...