This is a test

- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The British Muslim Convert Lord Headley, 1855-1935

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This is the first biography of Lord Headley, who made international headlines in 1913 when he defied convention by publicly converting to Islam. Drawing on previously unpublished archival sources, this book focuses on Headley's religious beliefs, conversion to Islam, and work as a Muslim leader during and after the First World War. Lord Headley slipped into obscurity following his death in 1935, but there is growing recognition globally that he is a pivotal figure in the history of Western Islam and Muslim-Christian relations; this book evaluates the strengths and weaknesses, successes and failures of the man and his work, and considers his significance for contemporary understandings of Islam in the Global West.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The British Muslim Convert Lord Headley, 1855-1935 by Jamie Gilham in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Biografías históricas. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

A conventional start

Early years, 1855–92

Rowland George Allanson-Winn, the future fifth Lord Headley, was born in London on 19 January 1855. The British newspapers on that cold and cloudy Friday were full of reports and opinion pieces about the Crimean War, which had begun in October 1853. Britain had been drawn into the conflict with its allies France, the Ottoman Empire and Sardinia against Russia, ostensibly to check further extension of Russian power in the vast but fragile Ottoman territories. Following a series of logistical and tactical failures and mismanagement, by 1855 the war had become unpopular in Britain. Ten days after Rowland’s birth, the British Parliament approved a motion for an investigation into the conduct of the war, which led to the resignation of the Conservative prime minister George Hamilton-Gordon, the fourth Earl of Aberdeen (1784–1860). The war continued for another year, but its wider concern, the so-called Eastern Question – the question of what should become of the Ottoman Empire as its subject peoples and their rulers sought autonomy or independence, encouraged and discouraged primarily by Russia, Britain and France – rumbled on for almost the entirety of Rowland Allanson-Winn’s long life.1 As is related in the subsequent chapters of this book, six decades later, after he had converted to Islam, Rowland found himself inexorably caught up in the politics of the Eastern Question and the decline of the Ottoman Empire and Turkey, which had, in 1517, declared itself the Caliph (or Khalifa), the successor to the mantle of the Prophet Muhammad and the leader of the universal Muslim community, or umma.

This chapter focuses on Rowland’s early life. After describing Rowland’s ancestry and family, it briefly documents his formative years at school and university to reveal that he led a conventional life, did well academically and excelled at sports. After university, however, Rowland struggled to settle on a career, and the period between the late 1870s and the early 1890s was marked by uncertainty and a lack of direction, compounded by the stirring of religious doubt. Rowland abandoned legal studies in favour of various professional jobs, including editorship of a newspaper and, in 1892, he attempted to become a Unionist politician in his ancestral homeland, Ireland.

Antecedents

Rowland George Allanson-Winn had a conventional upbringing. He was the eldest child of the Honourable Rowland Allanson-Winn (1816–88) and his wife, Margaretta Stefana (née Walker, 1823–71). The Winn family had risen in society during the late eighteenth century with George Winn (1725–98), who was one of the Barons of the Exchequer (judges of the court of common law) in Scotland from 1761 to 1776. In 1763, George Winn inherited the estate of a cousin in Little Warley, in the English county of Essex, and in 1776 he was created the first Baronet of Little Warley. In 1789, the first year of the French Revolution, George Winn became Tory Member of Parliament (MP) for Ripon in North Yorkshire and was rewarded for his support of William Pitt the Younger (1759–1806), who recommended his elevation to Lord Headley, Baron Allanson and Winn of Aghadoe in County Kerry, south-west Ireland, in 1797. George Winn assumed the surname and arms of Allanson by royal licence in 1777, but he used the double-surname of Allanson-Winn.2

The first Baron Headley was succeeded in 1798 by his eldest son, Charles Winn-Allanson (1784–1840; he curiously used the surname of Allanson after that of Winn), who also succeeded a distant cousin to become the eighth Baronet of Nostell in Yorkshire in 1833. With no sons to succeed him, Charles’ only brother, the Honourable George Mark Arthur Way Allanson-Winn (1785–1827) had issue, but he died aged forty-two in 1827. Therefore, when Charles Winn-Allanson died thirteen years later, the Baronetcy passed to his nephew and George’s eldest son, another Charles Allanson-Winn (1810–77), who became the third Lord Headley.

Although Ireland was part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (UK) until 1922, as Irish peers the Barons Allanson and Winn were not automatically entitled to a seat in the House of Lords. The third Lord Headley, Charles, was, however, appointed a Tory Representative Peer for Ireland in 1868. When Charles died after a long illness in 1877, he was succeeded by his eldest surviving son, Charles Mark Allanson-Winn (1845–1913), who was also appointed a Representative Peer for Ireland. To avoid confusion, the fourth Lord Headley was known in the family as Charlie Allanson-Winn.

In the early 1880s, shortly after Charlie Allanson-Winn succeeded to the Baronetcy, the family estate consisted of 12,769 acres in County Kerry (reduced from around 25,000 acres in the previous decade), valued at a modest £5,600 per year.3 The family fortune was already in sharp decline when Charlie became the fourth Baron, and the Headleys were cash poor. Nonetheless, the estate included a large late-Georgian villa, Aghadoe House (rebuilt c.1860), described when it was built as ‘a very fine building, densely shaded with trees’, and set on a model farm overlooking Lough Leane (or Loch Lein) near Killarney.4 Further estate property was located to the west of Aghadoe, at Glenbeigh on the mountainous Iveragh Peninsula. The superficial splendour of the Headley residences in picturesque Aghadoe and Glenbeigh contrasted with the poverty endured by tenants of the estate. Tensions between landlord and tenants increased during the nineteenth century because, as the Dublin Review noted in 1836:

In Ireland, unlike every other country, there scarcely exists any community of interest between landlord and tenant, though in bitter irony they are called ‘their benefactors’ – assuredly no other relation is recognized between the one and the other than that of buyer and seller, in mercantile language; the proprietor looks upon his land as so much merchandise, from which the highest rate of profit must be extracted, and in order to do so, the tenant is kept in a state of villainage like the vassal of a feudal baron to his superior.5

The Dublin Review included an extract from a report written several years earlier by a Mr Wiggins, ‘an English practical agriculturalist’, as illustrative of ‘what landlords, who know their own interests, may effect, and how easy it is to manage even the rudest and most ignorant boor by adopting kind and conciliatory measures’:6

Lord Headly’s [sic] estate of Glenbeg [sic], situated in a wild district of Kerry, at the entrance of the Iveragh Mountains, consisting of 15,000 acres, much of which is rocky, boggy, and mountain ground, was, in 1807, inhabited by a people, to whom the bare idea of labour was offensive, and work was considered as slavery, though a robust, active, enterprising, and hospitable race of peasantry.

Lord Headly resolved to cultivate their good qualities, without being at first very eager to punish their bad ones, and has succeeded in introducing a degree of improvement and cultivation, which without these effects, must have required a century. They are now well clothed, and as orderly and well-conducted as you see in any village in England. Agriculture has improved with very little sacrifice of rent or money.7

This English opinion piece would not have found favour among Headley’s tenants, for whom the absentee Barons and their land agents were brutal, exploitative men.

In an arrogant act of defiance against his tenants and other critics, during the late 1860s, the third Baron, Charles Allanson-Winn, built Glenbeigh Towers (1867–71), a medieval-style solid stone fortress, complete with a huge three-storey keep raised on a battered platform. In his classic guide to Irish country houses, the historian Mark Bence-Jones described Glenbeigh Towers as ‘a grim’ building, and noted that ‘the complete absence of battlements, machicolations and other pseudo-medieval features served to make the building more formidable’.8 Charles Allanson-Winn raised funds for the project by dramatically increasing the rents on his estate, which were enforced by a tough land agent. He was not, however, happy with the final result; the cost of construction spiralled out of control and the walls leaked. Charles Allanson-Winn threatened, but probably could not afford to sue, his architect. Glenbeigh Towers was – and is still – referred to locally as ‘Winn’s Folly’.9

Charles Allanson-Winn had a very difficult relationship with his son and heir, Charlie. It was exacerbated by endless concerns about money and not helped when, in 1867, Charlie defied his father’s wishes by marrying the ‘almost penniless’ widow, Elizabeth (‘Bessie’) Housemayne Blennerhassett (1846–1928), who was the daughter of a lowly Dorset clergyman.10 When Charlie Allanson-Winn succeeded his father in 1877, the Irish ‘Land War’, a period of civil unrest in which tenants rebelled against absentee landlords, was gathering momentum. Although Charlie sought to settle debts and duties by selling off land when his father died, the Headley estate remained heavily mortgaged.

As the fourth Lord Headley, Charlie Allanson-Winn did little to improve relations with his tenants. Thoroughly English (born in Brighton, educated at Harrow and Oxford), Charlie spent little time in Ireland until later in life; he served with both the English and German armies, travelled widely and preferred to live at Warley Lodge in Little Warley, Essex.11 The Lodge was part of the Baron’s modest English estate, which in the early 1880s comprised 1,038 acres in Essex and 2,235 acres in Yorkshire. Consequently, in 1883, the total family estate of a little more than 16,000 acres in Ireland and England was valued at £13,388 a year.12

Childhood

Charlie Allanson-Winn dropped ‘Allanson’ from his surname in 1883. By contrast, his uncle, Rowland’s father, who was born in 1817 and was a grandson of the first Lord Headley, used the surname Allanson-Winn without royal licence.13 Granted the rank of the Baron’s younger son, the Honourable Rowland senior was nevertheless heir presumptive if his nephew Charlie did not produce a son (he had one child, a daughter, when he became Lord Headley in 1877); and Rowland junior was next in line. Rowland senior and his wife Margaretta Allanson-Winn had three children after Rowland junior, all daughters: Helen Margaretta (1857–1941), Stephanie (1858–1940) and Margaretta Anne (1860–1951).

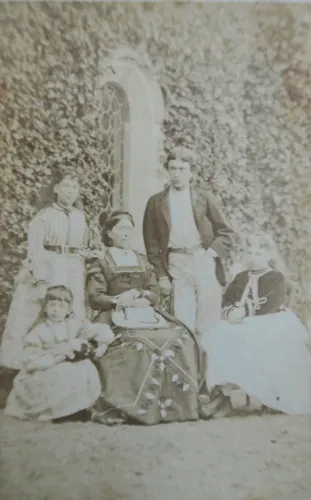

Figure 1 The Honourable Rowland George Allanson-Winn with his sisters and mother, Margaretta Stefana Allanson-Winn, Oxford, c.1869.

Source: Courtesy of Janet Webb / The Estate of the Fifth Lord Headley.

Source: Courtesy of Janet Webb / The Estate of the Fifth Lord Headley.

Rowland junior and his sisters were raised at the family home overlooking the prestigious Chester Square in London’s Belgravia. They also had the run of the Glenbeigh estate in Ireland, which was formally transferred to their father in the 1860s. Although Rowland senior complained about lack of money, the family lived well, attended to by several domestic servants.14 Rowland junior had a happy childhood and, though he later had a fractious relationship with his father, always recalled both of his parents with great fondness. He was educated privately in London except for a brief spell in 1868 at Westminster School, located in the precincts of Westminster Abbey. Two years later, in March 1871, tragedy struck the family when Rowland’s mother Margaretta died at the age of forty-seven. Rowland had just turned sixteen. Many years later, he wrote a ‘hymn’ called ‘The Power of God’s Love’, which recalled his loss:

When Thou didst take my mother dear

In early life to dwell with Thee,

I mourned her loss with many a tear,

And thought death gained a victory.15

Religion was important in the Allanson-Winn household. The family was firmly Protestant and worshipped in Anglican churches in London and Ireland. Late in life, Rowland desc...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Series

- Dedication

- Title

- Contents

- List of figures

- Acknowledgements

- Glossary

- List of abbreviations

- Note on quotations and spelling

- Introduction

- 1 A conventional start: Early years, 1855–92

- 2 Imperial engineer, 1892–1900

- 3 Troubles, 1900–13

- 4 Conversion to Islam, 1913

- 5 Muslim peer of the realm: The first decade, I: 1913–18

- 6 Muslim peer of the realm: The first decade, II: 1918–23

- 7 Pilgrimage to Mecca, 1923

- 8 Ambassador for British Islam, 1923–29

- 9 Twilight years, 1929–35

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Select bibliography

- Index

- Copyright