This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Breaking the Vicious Circle is a tour de force that should be read by everyone who is interested in improving our regulatory processes. Written by a highly respected federal judge, who would go on to serve on the Supreme Court, and who obviously recognizes the necessity of regulation but perceives its failures and weaknesses as well, it pinpoints the most serious problems and offers a creative solution that would for the first time bring rationality to bear on the vital issue of priorities in our era of limited resources.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Breaking the Vicious Circle by Stephen Breyer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

SYSTEMATIC PROBLEMS

We regulate only some, not all, of the risk that fills the world. Any one of us might be harmed by almost anything—a rotten apple, a broken sidewalk, an untied shoelace, a splash of grapefruit juice, a dishonest lawyer.1 Regulators try to make our lives safer by eliminating or reducing our exposure to certain potentially risky substances or even persons (unsafe food additives, dangerous chemicals, unqualified doctors). When the regulator focuses upon reducing exposure to a particular substance, when the risk is to health, when the risk is fairly small or uncertain, the regulator typically uses a particular system—a “heartland” regulatory system, the common features of which underlie many different statutory programs.

I focus upon this heartland system, using as an example the regulatory effort to reduce exposure to cancer-causing substances, both because of its illustrative power and because the public’s fear of cancer currently drives the system. Still, much of what I say about cancer and similar health risks has broader application to other regulatory screening efforts, for example, whether or not to require seat belts for infants in airplanes, or how to regulate swimming-pool slides.

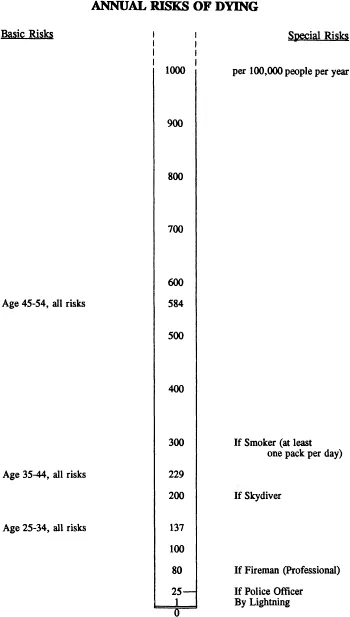

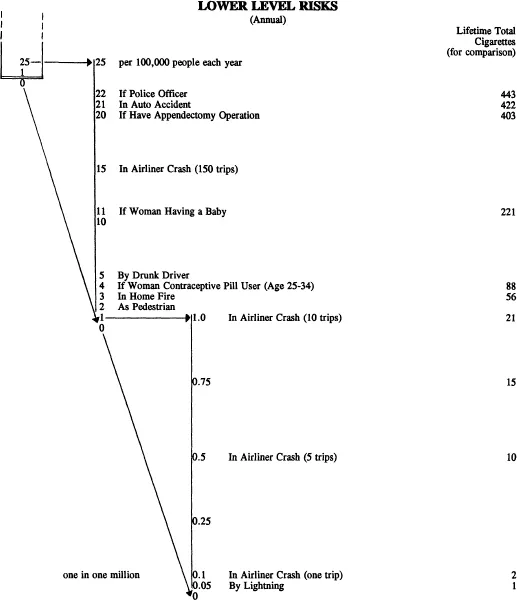

You need four pieces of background information. First, you need some idea of what I mean by “small risk,” the subject of many regulatory programs. The best device I have found for explaining the term is the “risk ladder” prepared by Robert Cameron Mitchell, of Clark University (Figure 1).2

About 2.2 million persons die each year in the United States, out of a population of 250 million.3 Knowing nothing about an individual person, one can assess a crude individual risk of death as just under 1 in 100, or 1,000 out of 100,000, as shown at the very top of the figure. If one knows a person’s age, one can make a more refined assessment, such as 137 out of 100,000 for all persons between 25 and 34. Certain individuals incur special risks of death because of their professions or their activities. A skydiver, for example, incurs a special annual risk of 200 in 100,000. Those special risks are shown at the right. The enlarged segment of the bottom of the ladder shows special small risks such as the risk of being killed by a drunk driver (5 in 100,000) or being hit by lightning (1 in 2,000,000).

Figure 1. Risk “ladder” showing annual death rates for basic and special risks.

Source: Robert Cameron Mitchell, Clark University.

Most people want to ask, “One in a million—is that a lot or a little?” There is no good answer to that question. If one focuses upon statistics, it may seem very little; if one tries to focus upon the 250 or so individual deaths that this number implies (in a population of 250 million), it may seem like a lot. Mitchell, who is an expert in trying to communicate this kind of information neutrally (he employs this chart to help elicit public reactions), uses a “cigarette equivalency” table, shown at the right of the lower-level risk ladder. It indicates that the risk of being hit by lightning is the same as the risk of death from smoking one cigarette once in your life, and it grades other risks accordingly. For present purposes, you should keep in mind that many of the regulatory risks at issue here are in the “blown-up” small-risk portion of the ladder.

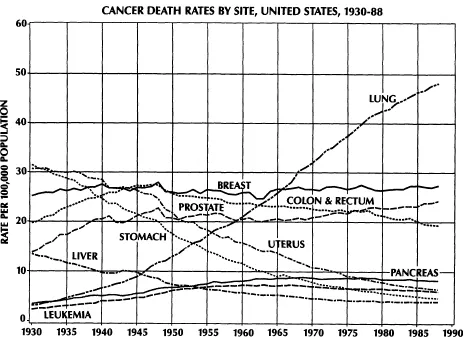

Second, you should know a few facts about cancer, the engine that drives much of health risk regulation. Of the 2.2 million Americans who die each year, about 22 percent, or 500,000, die of cancer.4 Just how many of these deaths are caused by exposure to substances that the government does, or might, regulate (such as chemical pesticides, various pollutants, or food additives) is the subject of considerable scientific dispute. Two leading authorities, Richard Doll and Richard Peto, in the early 1980s published important findings about the causes of cancer deaths (Table 1).5 The table suggests that “pollution” and “industrial products” account for under 3 percent, or less than 15,000, and “occupation” accounts for a further 4 percent, or 20,000, of all cancer deaths.6 Other, related scientific work indicates that substance exposure could account for up to 10 percent, or 50,000 deaths. The range of expert estimates seems to be roughly 10,000 to 50,000 deaths. Experts believe that only a relatively small portion of nonoccupational cancers are “regulatable.”7 By way of comparison, consider that smoking-related cancer accounts for 30 percent, or about 150,0, of those 500,000 deaths.8 You should also be aware (though this statement is more controversial) that the number of deaths from most of the major types of cancer does not seem to have been increasing, although there is some evidence of increases in the incidence of some, mostly less common, types of cancer.9 The graph shown in Figure 2, from the American Cancer Society, shows an enormous increase in lung cancer, a decline in stomach and uterine cancers, and a roughly constant incidence of other forms of cancer.10 In other words, the number of people who die each year from types of cancer whose incidence seems likely to be reduced by regulation is below an estimated ceiling that itself varies between 10,000 and 50,000; it is probably less than 2 percent to 10 percent of all cancer deaths; it is 7 percent to 33 percent of deaths associated with smoking. The numbers must range from less than 1 percent to less than about 3 percent of our 2.2 million annual mortality total.

Table 1. Proportions of cancer deaths attributed to various factors.

Percent of all cancer deaths | ||

Factor or class of factors | Best estimate | Range of acceptable estimates |

Tobacco | 30 | 25–40 |

Alcohol | 3 | 2–4 |

Diet | 35 | 10–70 |

Food additives | <1 | −5a–2 |

Reproductive and sexual behavior | 7 | 1–13 |

Occupation | 4 | 2–8 |

Pollution | 2 | <1–5 |

Industrial products | <1 | <1–2 |

Medicines and medical procedures | 1 | 0.5–3 |

Geophysical factorsb | 3 | 2–4 |

Infection | 10? | 1–? |

Unknown | ? | ? |

Source: Richard Doll and Richard Peto, The Causes of Cancer 1256 (1981). Reprinted by permission of Oxford University Press.

a. Allowing for a possibly protective effect of antioxidants and other preservatives.

b. Only about 1 percent, not 3 percent, could reasonably be described as “avoidable.” Geophysical factors also cause a much greater proportion of nonfatal cancers (up to 30 percent of all cancers, depending on ethnic mix and latitude) because of the importance of UV light in causing the relatively nonfatal basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas of sunlight-exposed skin.

Figure 2. Cancer death rates by site of cancer, United States, 1930–1988. Rates are adjusted to the age distribution of the 1970 census population. Rates are for both sexes combined, except breast and uterine cancer (female population only) and prostate cancer (male population only). Source: American Cancer Society, Inc., Cancer Facts and Figures, 1992. Used by permission.

Third, you must keep in mind that regulation designed to screen out risky substances, including cancer-causing substances, is embodied in many different regulatory programs—indeed, in at least twenty-six different statutes administered by at least eight different agencies.11 This alphabet soup of agencies and programs includes such old friends as EPA, DOL, HHS, and NRC, administering, for example, CERCLA,12 TSCA,13 FIFRA,14 CAA,15 OSHA,16 FDCA,17 and AEA.18 The rules and orders may vary from program to program, sometimes denying permission to market a product, sometimes insisting upon a cleanup, often setting some kind of “dilution” standard above which a product’s maker, shipper, or user must provide...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 Systematic Problems

- 2 Causes: The Vicious Circle

- 3 Solutions

- Notes

- Index