This is a test

- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

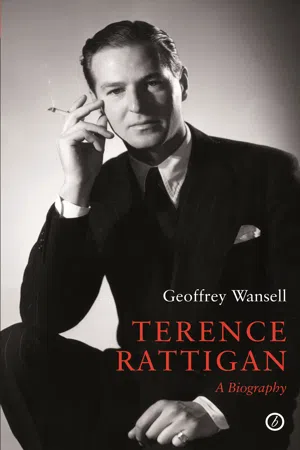

Terence Rattigan: A Biography

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The greatest plays of Terence Rattigan (1911-77) - including The Browning Version, The Deep Blue Sea, Separate Tables and The Winslow Boy - are now established classics. There have been regular revivals of his work, including recent productions in the West End, at Chichester Festival Theatre and by the Peter Hall Company, which makes the first paperback edition of Geoffrey Wansell's acclaimed biography particularly timely. From the heady days of Rattigan's early success to the darker days of his decline in popularity, Wansell paints a captivating portrait of one of the twentieth century's greatest theatrical lights.

Geoffrey Wansell is vice president of the Terence Rattigan Society: www.theterencerattigansociety.co.uk

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Terence Rattigan: A Biography by Geoffrey Wansell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism in Drama. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

LAND OF HEART'S DESIRE

I remember my youth and the feeling that will

never come back any more – the feeling that

I could last forever, outlast the sea, the earth,

and all men; the deceitful feeling that lures us

on to perils, to love, to vain effort – to death.JOSEPH CONRAD

The Rattigan family were Irish bred, Protestant by religion, and imbued with a distinctive spirit of adventure and determination. Their rise began in the 1840s, when Bartholomew Rattigan of County Kildare decided to exchange the mist and peat fires of his native Ireland for more exciting prospects. He emigrated to India with his new young wife and their first child, a son, after accepting a post in the ordnance department of the East India Company. Two years later a second son was born.

Both sons prospered in their adopted land. The elder, Henry Adolphus Rattigan, became an advocate and author of standard works on Indian law, notably as it applied to divorce among Christians and Indians, and ended his career as Chief Justice of the Punjab. But his fame was eclipsed by that of his younger brother William, the real founder of the Rattigan family's reputation.

‘A self-made man, without advantage of family influence’ was how the Dictionary of National Biography was to describe this archetypally resolute and gifted Victorian after his death in 1904, at the age of sixty-one. Educated at the High School in Agra, William Henry Rattigan went straight into Government service as an assistant commissioner in the Punjab. Before the age of twenty he was acting as a judge in the ‘small causes’ court in Delhi.

A year after his marriage to an English colonel's daughter, Teresa Matilda Higgins, whose father was examiner of accounts in the public works department, he resigned his post with the Government and started to study the law in India, recognising how important a sound legal system would become to the country so rapidly developing around him. When the Punjab Chief Court was established in 1866, William Rattigan rapidly built himself a successful advocacy practice. He was twenty-four.

In 1871, at the age of twenty-nine he was well enough established to return to London to complete his legal education. He was admitted as a student at King's College in the University of London and at Lincoln's Inn, where he was called to the Bar in June 1873, having passed his law examinations with first class honours. England did not attract him, however, and with his growing family of four sons and two daughters, he lost no time in returning to India. Within four years he was Government Advocate, and therefore chief prosecutor, in Lahore, a position that put him, in the words of a later Indian Government report, ‘at the height of his profession’. During the 1880s he also acted (in between his periods of advocacy) as Judge of the Chief Court of Lahore.

Both in association with a colleague, Charles Boulnois, and on his own, William also helped to construct the first reference books on Punjab law. His book The Civil and Customary Law for the Punjab, first published in 1880, is still the standard text on the subject, with editions published well into the 1960s. He also found time to write books on Hindu law, including The Hindu Law of Adoption, as well as to complete a treatise on the history of India from the invasion of Alexander ‘to the latest times’ – ‘with introductory remarks on the mythology, philosophy and science of the Hindus’.

An exceptional linguist, Rattigan had mastered the five major European languages within a few years of the end of his schooldays in Agra, and went on to learn not only several Indian dialects – and their vernacular – but also Persian. Shortly after his fortieth birthday, and while still acting as Chief Advocate in Lahore, he found time to take a doctorate in German at the University of Göttingen.

His enthusiasm for the Indian Bar was beginning to wane, however. In November 1886 he resigned his judgeship to concentrate on advocacy, but within three months had accepted the vice-chancellorship of the then all but bankrupt (and only recently founded) Punjab University. In the next five years he saved it from financial ruin, for which its grateful Court awarded him a Doctorate of Law and reappointed him biennially until he resigned in 1895. He also became President of the Khalsa College Committee, and thereby helped to establish education among the Sikh community. A hospital named in his memory in the college was established after his death by the Sikhs of Amritsar in recognition of his work.

Knighted by Queen Victoria in 1895 and appointed a QC in 1897, he eventually decided to return to England to practise before the Privy Council as one of the few barristers with substantial experience in the Indian courts. He was by now long remarried. His first wife had died in 1876 and two years later he had married her younger sister Evelyn, with whom he proceeded to have a further three sons, bringing the total number of his children to nine. Encouraged by Evelyn, he entered politics, but his career in the House of Commons was short-lived.

In the ‘khaki election’ of October 1900, Sir William Rattigan stood ‘in the liberal unionist interest’ as a candidate for the Scottish seat of North East Lanarkshire, and went so far as to name his new London residence (a large house recently constructed in Cornwall Gardens, South Kensington) Lanarkslea, in the constituency's honour. He failed to get elected at the first attempt, but shortly afterwards, in September 1901, he won the seat at a by-election, with a majority of 904.

But his health was weakening. The intense demands he had put upon himself in India had taken their toll, and by the beginning of 1904 he was too ill even to speak in the House. In the spring of that year he told the Government whips that he was going to take the summer off and retire to his Scottish constituency in an effort to recuperate. On the morning of 4 July 1904 he and Lady Rattigan set off for Scotland in the back of their chauffeur-driven Darracq. Sir William had not returned from India loaded with wealth, but he adored new inventions, and particularly the motor car, even though these contraptions, in the words of the historian Sir Robert Ensor, aroused intense feelings about the ‘selfishness of arrogant wealth’ as they dashed along the old narrow untarred carriageways, ‘frightening the passer-by on their approach and drenching him in dust as they receded’. Sir William's Darracq would certainly have done that. On this occasion, while passing Langford, a village near Biggleswade in Bedfordshire, on the way north, however, the spokes of the rear wheel shattered as the car rounded a corner, and the vehicle overturned.

Sir William was thrown out of the open car. His neck was broken instantly. Lady Rattigan and the chauffeur, John Young, survived because they remained inside, crumpled together in a heap. The Coroner suggested two days later that the car may have been in need of some mechanical attention, which Sir William had refused to allow it to have, and that the luggage piled on the roof at the rear had made it unstable. He nevertheless recorded a verdict of accidental death. Three days later, Sir William Rattigan KC, MP, the founder of the Rattigan dynasty, was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery in London.

The headship of the family now passed to his eldest son, William Frank, always called Frank, a young man who displayed the familiar Rattigan loquacity and charm but totally lacked his father's gravitas. Frank had already embarked on a promising diplomatic career, and at the moment of his father's death was about to take up his second posting, as an attaché at The Hague. Handsome and distinctly dashing, and with an eye for pretty girls, he realised, however, that a young diplomat with ambitions needs a wife, and on 2 December 1905, at Christ Church in Paddington, Frank Rattigan married Vera Houston, daughter of Arthur Houston KC, barrister, bankruptcy expert, authority on English drama and former don, the child of another itinerant Irish Protestant family. Vera Houston, who lived with her father at 22 Lancaster Gate on the northern edge of Hyde Park, was then just twenty, with flaming red hair that streamed down to her shoulders in waves, and a slight lilt to her voice. Slim, effervescent, and undeniably pretty, she was to be Frank Rattigan's long-suffering wife throughout the rest of his life.

The union of these two Irish families provides the first clues to the character of their second son. Irish though they were, neither Frank nor Vera thought much about religion. An Irish Protestant does not perhaps suffer the haunting guilt that his Scottish equivalent might. The Rattigans lived life to the full, and that is how their second son, Terence, was to be brought up.

Frank Rattigan had spent the first ten years of his life with his father in Lahore, looked after by a full complement of servants but not overly supplied with much in the way of hard cash. Sir William Rattigan was more likely to present his eldest son with a rifle and six cartridges – to shoot whatever food he could – than to give him money. Around Christmas Sir William would take two- or three-week holidays to go shooting in the Himalayas, and years later Frank was to recall, ‘I sometimes sat up with him all night, waiting for the tigers and leopards, and learnt to control my nerves’. It gave the boy an appetite for shooting which he was never to lose. It also gave him a taste for a life surrounded by servants.

Frank came to England in 1888, at the age of ten, to study at a preparatory school, Elstree near Newbury in Berkshire, in preparation for Harrow. Presents of books from his father and mother would arrive from time to time to alleviate the austere school lifestyle. Like other boys in his position, he travelled home to India only rarely, though there was no sign that he suffered – as so many of his contemporaries did – from the fear that he would never recognise his parents when he saw them again. He was a confident boy, who turned into a fine cricketer. The masters at Elstree were ‘nearly all famous cricketers’, he recalled later, and their coaching stood him in good stead.

Frank arrived at Harrow in 1893, sweeping into the school with effortless assurance and charm. He was no Tom Brown, frightened of the shadow of Flashman, but a boy happy in the knowledge that he was one of England's chosen few. So great was his enjoyment of his time at the school that a decade later he donated a plaque to the chapel when his father was killed in the summer of 1904.

His two brothers also went to Harrow. Gerald, the next senior, who stayed for just two years, from 1896 to 1898, was the only one of the three not to go on to university. He became a clerk in the Principal Probate Registry. Like his father, he was killed in a motor accident, in 1934.

Cyril, the youngest, stayed at the school for the full period, from autumn 1898 until the summer of 1904. He became a Monitor (Harrow's equivalent of a prefect), was picked to play against Eton in the annual cricket match at Lords (though he missed the game through illness), and played for the school cricket eleven in 1903 and 1904 before going on to Trinity College, Cambridge. He was killed in Flanders in 1916, serving as a captain in the Royal Fusiliers.

Neither brother could rival Frank's success, and particularly his success on the cricket field. In his first year, at the age of barely fourteen, there was a strong possibility that Frank might be asked to play for the Eleven against Eton in June. In the end, he was adjudged too young, but the following summer he made the Eleven and was awarded his ‘flannels’, a significant honour. Like Cyril, he was to miss the first match through illness, but was to play against Eton in the next three matches, in 1896, 1897 and 1898, with considerable distinction. The swashbuckling Frank Rattigan became something of a Harrow cricketing legend.

In 1898 he went up to Magdalen College, Oxford, where he played cricket in the Freshmen's match, scoring a century, but did not get a trial for the University side in his first year. By then he had decided to leave Oxford and join the Diplomatic Service, which his father had urged upon him. This necessitated going abroad to learn French and German. He went first to Hanover and then to Compiègne.

In Hanover he lodged with a stern German lady used to ‘young English gentlemen preparing for the Diplomatic’, and made friends with another student, Lionel de Rothschild. Both young men experienced the wave of Anglophobia that was sweeping Germany in the first years of the century, but neither was unduly disconcerted by it. At Compiègne the hostile atmosphere he had experienced in Germany did nothing to prevent Frank from indulging his favourite pastimes – gambling, shooting and flirting with pretty girls. On his return to London he finished his course of cramming under the tutelage of the formidable and renowned W B Scoones, and in the autumn of 1902 he filled the third of the three places available to entrants for the Diplomatic Service in the autumn examinations. He joined the service, spent a year as a Foreign Office clerk in London, and in March 1904 was posted to Vienna as a junior attaché.

This was the life. ‘The Vienna season,’ he was to reminisce later, ‘was an endless whirl of gaiety, what with the numerous Court Balls, those given by the leading Austrian families, and the picnic dances subscribed for by the bachelors in society.’ The new attaché was also to gain a moment of fame dancing the polka with the future Queen Mary, wife of George V. (‘I was far from being an expert at this particular dance; my royal partner and I created some devastation in the ballroom, by bumping into other couples and sending them flying.’)

A mere three months later he was posted to The Hague. ‘It was in Holland,’ he was to write later, ‘that I first developed an interest in collecting antiques of all kinds, and I travelled all over the country in the search for Delft, old books, furniture and prints.’ He augmented his modest income by discreet dealing in furniture and pictures. It was here too that he brought his new young wife Vera in 1906.

Frank Rattigan was an embroiderer of the truth. In his memoirs, Diversions of a Diplomat, published in 1924, he writes that his new young wife was ‘seventeen when they married’, yet the marriage certificate he signed shows clearly that she was twenty. This trait was one of many that Vera Rattigan was to discover about her new husband. For the moment she was more than enchanted to be whisked off to The Hague, there to be fêted by other diplomatic wives, smiled at by ambassadors and introduced to the many pleasures of this glittering world. The idyll was interrupted only by her pregnancy. On 24 October 1906, nine months after her arrival in The Hague, Vera gave birth in London to a boy, Brian William Arthur.

The child was born with a physical deformity. His left leg was severely shorter than the right, and there were indications that there might be some brain damage. Vera was desolate. She felt she had failed, but Frank seemed unperturbed. His smile was still as warm, his words as consoling. There was no question, however, of taking the baby back with them to The Hague. Brian would stay in Kensington with Lady Rattigan, to be looked after by a nanny and given all necessary medical care.

By the time Frank Rattigan got round to officially registering his son's birth – something he did not manage until 1 December – he knew that he and his wife were already destined for a new posting, the Tangier Legation. After the New Year celebrations in England, and a brief trip to Holland, they set off for Morocco.

Just getting to Tangier proved to be an adventure. The city had no formal harbour, which forced visiting steamships to anchor on the tide and wait for flat-bottomed rafts to be rowed out to transport the passengers and their luggage ashore. The wife of a French chargé d'affaires and his children had been drowned in the process, and when the Rattigans arrived in a storm they were in fear for their lives. ‘We had a terrible time during the row to the shore,’ Frank wrote,

and were several times nearly swamped by the tremendous following waves. However, we did eventually reach the quay, soaked to the skin but alive. Under the escort of Legation soldiers, who had been sent to meet us, we fought our way through the hordes of yelling donkey boys, mounted the horses provided for us, and clattered up the slippery cobble-paved streets to our hotel. It was too rough to land our baggage for two days, and we were obliged to remove our soaking clothes and retire to bed, until our chief and his wife kindly came to our assistance with spare clothes.

Frank and Vera Rattigan were to become popular members of the distinctive expatriate community of Tangier over the next four years. They won the mixed d...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-title page

- Geoffrey

- Title

- Copyright

- Toc

- Preface

- Prologue: Nature's Shift

- 1 Land of Heart's Desire

- 2 Father of the Man

- 3 Harrow

- 4 Lord's

- 5 Oxford

- 6 First Episode

- 7 Without Tears

- 8 The Albatross

- 9 After the Dance

- 10 Escape

- 11 A One-Hit Wonder?

- 12 Shaftesbury Avenue

- 13 A Secret Life

- 14 The Crock

- 15 Noble Failures

- 16 My Father, Myself

- 17 Hester or Hector

- 18 Aunt Edna's Entrance

- 19 Table by the Door

- 20 Never Look Back

- 21 Theme and Variations

- 22 The Bubble Bursts

- 23 The Heart's Voices

- 24 The Twilight of Aunt Edna

- 25 The Movies, Hollywood, Everything

- 26 The Memory of Love

- 27 Death's Feather

- 28 Pretend Like Hell

- Select Bibliography

- Stage Plays, Feature Films and Television Scripts

- Index