eBook - ePub

Untitled Memoir

About this book

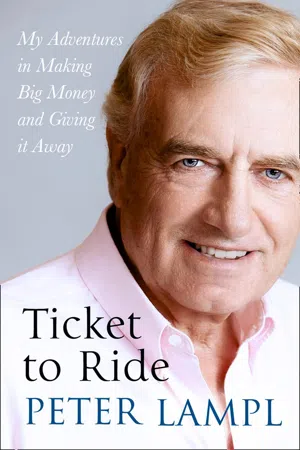

The candid tale of one of Britain’s most outstanding contemporary philanthropists.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

ON THE BRINK

Allow me to offer you a solid-gold business tip: in a high-stakes deal, when push is coming to shove and the future of your entire company is on the line, never underestimate the value of windsurfing.

It was September 1984 and I had flown to Seattle to try and persuade the president of the biggest privately owned forestry products company in America to sell me part of his business. To say I had a keen interest in clinching this deal would be putting it mildly. Twenty-one months previously I had quit my job as president of International Paper Realty in New York. That was a good, handsomely paid executive position in a huge company: at the time International Paper were the largest private landowners in the world, with vast holdings – 8.5 million acres, roughly equivalent to the area of Massachusetts and Connecticut combined. I had been head-hunted to work for International Paper from the Boston Consulting Group, which I had joined after graduating from London Business School. BCG were the world’s leading management consulting firm, but after four years of consulting I wanted to get some hands-on general management experience under my belt. International Paper certainly provided it. I was responsible for the company’s timberland deals (we were by far the biggest player in the North American market) and property developments, in which role I spent a fair amount of time flying around America looking at golf and ski-resort developments. There are worse jobs.

Yet I was ambitious and restless, with a strong entrepreneurial streak, and I yearned for independence and the chance to build something of my own. So, aged 35, I left my job and all its comforts and certainties, and set up on my own, ploughing some money I had saved into founding what I christened the Sutton Company,* with a smart Manhattan office on 45th and Third Street – its balcony offering a wonderful view of the Chrysler Building – and a plan to do deals in what had become my area of expertise, timberlands.

However, in the 21 months since foundation, the total number of acquisitions the Sutton Company – this bold new break-away venture of mine – had successfully landed could be calculated very quickly: none.

Which is to say, none whatsoever. Zero.

This was not for the want of trying. On the contrary, since the company’s inception, I had spent practically every waking hour hunting down and scrutinizing plausible projects, and I had got a long way down the line with a couple of them. But thus far my best efforts to close a deal had fallen victim variously to bad luck, bad timing, other people’s unscrupulous practices and even a sudden and unforeseen outbreak of New York family warfare.

There was, for instance, the deal I got involved in with the American industrialist Peter M. Brant, a piece of business which had looked promising when I embarked upon it, but, alas, quickly devolved into a long and winding lawsuit.

Brant was one of those high-living characters that the eighties American business world seemed to throw out in unusual quantities – the kind of person who commissions Andy Warhol to paint their cocker spaniel.† As well as art and spaniels, Brant was absorbed by polo, which he played to a high standard, and he had stakes in racehorses, including the famous Swale, which won the Kentucky Derby and Belmont Stakes in the same year (1984) and then mysteriously collapsed and died eight days later. The walls of Brant’s office in Greenwich, Connecticut, were practically papered with photos of him standing next to a horse which had just won a ‘Stakes race’, as he would proudly tell you. He was also the owner of Conyers Farm, an enormously covetable tract of land in Greenwich, Connecticut, which he had converted into high-end residential where people like tennis player Ivan Lendl and actor Tom Cruise had homes.

Growing up in Queens, Brant had been the schoolboy pal of a certain Donald J. Trump. Apparently Brant and the future 45th President of the United States would sometimes venture into Manhattan together on Saturdays and stock up on stink bombs and fake vomit at a novelty store. Some would say they retained a fair bit in common beyond those days. Both were the privileged sons of successful businessmen and both possessed an unashamed brashness and a certain willingness to cut corners and nudge the boundaries both at work and at play. I once had the pleasure of playing Brant at squash. (In the eighties, the squash court was arguably second only to the golf course as the recreational space in which business got done.) I’m not saying the guy cheated exactly, but there was an awful lot of ‘accidental interference’ in the course of our rallies and a suspiciously high number of lets. In due course, Brant would try nudging the boundaries of fair play with the IRS, which would not turn out so well. He was eventually sentenced to three months in jail for tax evasion.

But at this point, that particular twist in the story still lay ahead. In the early eighties, when I became involved with him, Brant had successfully expanded his father’s newsprint business, Brant-Allen Industries, and was an extremely important player in that area. One of his newsprint mills, acquired in partnership with the Washington Post, was in Ashland, Virginia, and Brant was looking to buy some additional timberland around it to guarantee more independent supply.

Which is where I came in, with my brand-new Sutton Company. Why would Brant be interested in partnering with me and my as yet unproven start-up? Well, I had my reputation in this area, after those years at International Paper. I also had thick, cream, headed notepaper – the most sumptuous headed notepaper I could find. I had the notepaper for the same reason I had the smart office with a balcony on 45th Street: because appearances matter. They always have, and they always will, but in the ultra-showy eighties, they possibly mattered even more than usual. I certainly at that time didn’t want anyone thinking I was running some kind of low-budget, amateur, kitchen-table operation. I remember Brant running his fingers over a sheet of luscious Sutton Company stationery and saying, ‘My God, this stuff would make a schoolboy smile on a Monday morning.’

In collaboration with Brant, I went to work, helping strike the terms for a deal to acquire the desired additional timberland around the Ashland mill. Brant and I eventually travelled to Washington and I attended a meeting in the Washington Post’s boardroom with the Post’s legendary chairwoman, Katharine Graham, where the company approved the purchase. Everything was flying. I stood to earn a percentage of the deal. By my calculations, the Sutton Company would make at least half a million dollars.

It was soon after this, though, that Brant and I found ourselves somewhat at variance over the nature of our relationship. With the deal concluded, he began to imply that my role all along had been merely as a consultant. This apparent change of heart, and Brant’s seeming determination to stand by it, caused me reluctantly to bring in a lawyer.

At the deposition, Brant gave no indication that he was particularly pleased to be there, or that he was taking the matter especially seriously. At some point in our dealings, I had made the mistake of addressing a letter to ‘Peter Brandt’, inserting a ‘d’, because when I heard the name ‘Brandt’ in those days, I automatically thought of the German Chancellor, Willy Brandt.‡

This now came back to haunt me. ‘You can’t even spell my name!’ he bellowed. He also seemed highly inclined to wave our claim away. ‘Ah, he’s just trying to make money out of me,’ he said at one point.

To which my lawyer rather pointedly replied: ‘Mr Brant, some of us have to make a living.’

The best moment of all came when we pointed out that we had evidence of payments to us from Brant indicating someone working on a success fee basis, which was higher than the kind of fee that might be paid to a consultant. Brant’s explanation for this discrepancy was as follows: ‘It’s like when you’re having your shoes shined. You give the guy a buck, and if you think he’s done a good job, you give him a buck more.’

Neither I nor my lawyer was particularly satisfied by this argument, and although I was pleased to hear that Brant thought I had been doing a good job, I didn’t relish the implication that I was some kind of shoeshine boy. Do shoeshine boys have high-quality thick cream notepaper? I think not.

Anyway, none of this was making the Sutton Company any richer. The case rumbled on, and, at the point at which I flew into Seattle, wouldn’t be resolved for another four years.§

Then, even more dispiritingly, there was the situation I had got into while attempting to buy a bankrupt treated wood company in New York State. This was low-hanging fruit, maybe. Certainly when I founded the Sutton Company I had been setting my sights a little higher than offcuts left on the floors of the bankruptcy courts. But I definitely saw some potential in this particular business. Once again, it was in an area that I understood. I had looked at it very closely and I was confident that I could manage the business back onto its feet and turn it around. What’s more (and this was definitely attractive), I was, so far as I understood, the only buyer in the frame.

My friend Charlie Evans put together a crucial piece of the financing. The bank EF Hutton, now defunct, were persuaded to put up the rest. The treated wood company, by the way, was called Dutton. So we had Sutton buying Dutton with financing from Hutton. Sutton, Dutton, Hutton … We seemed to be arranging a bankruptcy buy-out and writing a Roald Dahl children’s story at the same time.

Still, we had done all the painstaking prep work. Everything was in place – the price was agreed with the seller, the contracts were drawn up, the bank financing was there – and the only hurdle that remained was the obligatory court hearing at which the sale would be officially approved.

On the appointed date, Charlie and I drove out to the unromantic destination of Poughkeepsie in the Hudson Valley to complete the formalities, fully expecting to see the judge bang the gavel – or at least bring down the ink-stamp – and hand us the paperwork. Finally the Sutton Company was going to own something.

To lend the moment the grandeur it clearly merited, I rented a Cadillac for our 140-mile round-trip – a giant black whale of an automobile. Appearances again: I wanted to turn up in style and look like we had some money, and on this occasion a compact simply wasn’t going to cut it. The rented Caddy was suitably large and imposing. Unfortunately, as I discovered when I got behind the wheel, it was also a complete lemon. The suspension was shot and it was all I could do to keep the car’s massive frame on the road in a straight line. Charlie and I bounced up the Taconic State Parkway as though we were riding a rubber ball.

Consequently we were both pretty queasy by the time we walked into that drab New York State court room. We were also immediately mystified to discover a number of other people already present – two clusters of them, to be exact, on opposite sides of the room. Spectators? Apparently not. The judge began the proceedings and formally declared our agreed price for the company. At that point, a voice piped up from the left-hand corner of the room and made a counter-offer, slightly higher than ours.

This was not in the script. Charlie and I looked at each other in astonishment, then quickly scrambled together our response. There was a small amount of slack in our bid. We put in a counter-offer to the counter-offer. Without hesitation, the voice from the left-hand corner of the room piped up again, lodging another bid.

The judge now looked at us expectantly. It seemed an impromptu auction was under way.

Charlie and I conferred again, then lodged another offer. Back came the left-hand side of the room.

This went on for a few minutes until our carefully prepared bid was in shreds. We couldn’t go any higher. We were out. We held our hands up in sad surrender and began to gather together our things. At which point a third voice piped up, this time from the right-hand side of the room. And off the auction went again, left side against right side now, the price rising higher and higher. Charlie and I sat open-mouthed between these mystery bidders, our heads swivelling from side to side as if we were watching a game of tennis. Meanwhile the price of the busted company soared ridiculously skywards.

Still the auction went on, and still the price rose. Eventually, thoroughly dejected, we put on our coats and left them to it.

Back in Manhattan, after a long, largely silent and annoyingly bouncy drive home in the terrible rented Caddy, we stopped in at Charlie’s apartment, where we were greeted by his wife, Kathy, in a state of excitement.

‘Charlie! Charlie! What happened?’

Charlie pulled the pockets out of his trousers and said mournfully, with his slow Arkansas drawl, ‘Kathy, we just ran out of money.’

The next morning, still deflated, I got into the office at 7 a.m. and at 7.30 the phone rang. It was the victorious bidder.

‘Why would you be calling me now?’ I said.

It turned out that the guy didn’t really want the company at all; he simply hadn’t wanted the people on the other side of the room to have it. Apparently Charlie and I had inadvertently got caught in the middle of a turf war between two long-established and bitterly opposed New York families. Unbeknown to us, the tennis match we had been watching in that Poughkeepsie court room was Hudson Valley v. Long Island. The Hudson Valley guys’ sole purpose was to keep the Long Island guys off their patch. Having triumphantly accomplished that mission, Team Hudson Valley had woken up bright and early to find themselves the owners of a bankrupt treated wood company for which they had no real use or desire. So, my caller’s question, at 7.30 in the morning, was: would I like to take the thing off his hands?

‘Well, sure – but for how much?’

He quoted a price so high, and so far beyond our means, that I would have honked with laughter if I hadn’t been so close to screaming with frustration.

So, game over. Another fresh-air shot. More wasted motion for the Sutton Company. Thousands of dollars burned in legal fees and bank charges, and nothing to show for it. Add that to 21 months of rent on a plush midtown office which had started to look a touch hubristic and 21 months of salary for a secretary, plus a pricey ongoing legal case ticking away in the background. Not to mention the cost of the notepaper. As the savings drained away, in order to keep the company floating, I had sold my New York apartment on Beekman Place and moved into a rental. Now I put a second mortgage on my house on Long Island. The clock was officially running down. If something didn’t come good soon, the Sutton Company would be winding up before it had really started, my dreams of independent entrepreneurship would be in tatters and I would be slinking away from the wreckage with my tail between my legs.

This, then, was the state of play when my flight from New York landed in Seattle that afternoon in 1984. It was one last roll of the dice, frankly, although, for obvious strategic reasons, I wasn’t going to let it appear to be so. I was there to try and strike a deal with a man called Furman Moseley, who was president of the Simpson Timber Company, a huge American forest products concern dealing in timberland, pulp, paper and corrugated packaging. The part of the business that I wanted to buy was a distribution company supplying building materials to the trade. It represented a negligible fraction of the vast Simpson empire, in truth. The company was haemorrhaging money and Simpson wanted to get shot of it. But, once again, the business was in an area that I knew something about, and it was a distribution company, which I liked because it’s easy to make changes to distribution companies. I had done the research, looked into the background very thoroughly, and thought I saw something there that I could turn around.

I had initially been alerted to the sale by Donald P. Brennan, a man to whom my career owes a lot. A tough Irish-American who could scare the life out of people and rather enjoyed doing so, Brennan had been my boss at International Paper and had then taken up a post heading merchant banking at Morgan Stanley. He would occasionally call up and toss me bits and p...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Note to Readers

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 On the Brink

- 2 Setting Up Home

- 3 Ticket to Ride

- 4 On Trial in Oxford

- 5 Confessions of a Drug Dealer

- 6 Getting Down to Business

- 7 Cash Cows and Question Marks

- 8 Seeing the Wood for the Trees

- 9 Making Some Money

- 10 Making Some More Money

- 11 Dunblane and After

- 12 Back to School (and Back to College)

- 13 Open Access

- 14 Socially Mobile

- 15 My Vanishing Act. And My Reappearing Act

- 16 Entrepreneurial Philanthropy for All

- Afterword

- Acknowledgements

- About the Publisher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Untitled Memoir by Sir Peter Lampl in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.