ONE

What if the postmetropolis is Lusaka?

Introduction

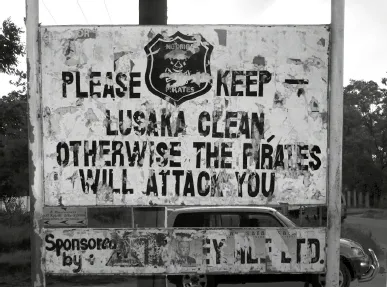

In June 2004, I stood with several American friends waiting for a minibus in Roma, a hilly neighborhood in the eastern part of Lusaka, Zambia. The hoot of the minibus horn caused me to turn my head and look up the street, and to notice a fancy new sign planted by the bus stop. In bright letters at the top of a square board covered by an elaborate green awning, the sign read ‘Please Keep Lusaka Clean.’ It was the bottom of the sign which really caught my attention: ‘Otherwise the Pirates Will Attack You.’ A black shield identified something called the ‘Ng’ombe Pirates’ with a pirate flag and skull-and-crossbones insignia (Figure 1.1).

This sign appeared on a Lusaka street long before piracy on the high seas off the East African coast gained the world’s attention, and Zambia is, after all, a landlocked country. Thus, after my friends and I boarded the minibus, we debated, with some good humor, about who the Ng’ombe Pirates might be. The Pirates of Zambia’s football league are the team from Livingstone, not Lusaka, so it wasn’t a football reference. Was Roma, an elite, formerly whites-only township until its forced incorporation into Lusaka in 1970, infested with pirates from the poor informal settlement, adjacent to it, Ng’ombe? Were there pirates among us – either us foreigners or our fellow passengers who had entered the minibus on the previous stops, all of which are located in Ng’ombe, in which Roma’s maids and gardeners live? If so, what was their role: did they help keep the city clean by attacking its polluters, or did the city end up more vulnerable to evil pirate attack if its citizens did not clean up? Was there a new pirate movie playing at the cineplex of the shiny new South African-owned shopping mall, Arcades, to which the minibus was heading? Or were the pirates merely metaphorical phantoms deployed by the clever advertising department of the sponsoring company, Harvey Tile, to make people dispose of their garbage?

FIGURE 1.1 The pirates of Ng’ombe (source: Simon Nkemba)

I have never located the pirates of Ng’ombe, nor have I found the answer to the question of the sign’s intent (five years later, it was covered with political campaign posters that a Zambian friend, Simon Nkemba, cleaned off to take this photograph). But I have found myself thinking of how the message, site, situation, and experience of the sign encapsulate my understanding of themes that predominate in many cities in Africa and writings about them. First, even forty or fifty years after the end of formal colonial rule, it is easy to see colonialism’s scars, as in the gashes of space and injustice that separate the Romas and Ng’ombes of many cities on a continent where every country but Liberia spent at least some years being ruled by Europeans. Second, the bouncing, fluid chaos of the minibus ride, with the spontaneous relationships passengers made with one another, re-creates countless times a day in myriad ways in almost any major city the informal interactions that encapsulate much of everyday life and economy in many versions of urban Africa.

The sign itself was attempting to encourage cleanliness, to build on a decade of awareness-raising about the environment, made most manifest in Lusaka in governance programs for solid waste management. The garbage around the sign’s base when we first saw it in 2004 and when Simon took the photo in 2009 made a mockery of these attempts. The rise of efforts to promote urban environmental planning and good governance is similarly hard to miss across Africa, and similarly struggling nearly everywhere. The everyday struggles of the ordinary residents of places like Ng’ombe, where residents told me in 2003 interviews that two or three armed robberies may happen each night, parallel those of informal settlement residents in many African cities. Most of Lusaka’s residents live in substandard housing in such settlements, which are often illegal (or ‘unauthorized’ in local parlance), crime-ridden, struggling with HIV/AIDS, and home to many refugees from past wars in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Angola, or Mozambique. This too is a theme one finds resonating across many African cities, wounded and limping into the second decade of this new millennium.

Yet in Lusaka, the marks of globalization, a transformed modernity, and a distinctive cosmopolitanism, like the Arcades mall, are fast becoming visible, as they are in many African urban areas. Through this globalizing trend, perhaps, we return to the pirates. Much of what happens in African cities is invisible or unpredictable and might seem bizarre to the unfamiliar visitor, like those Ng’ombe Pirates. Sometimes, this invisibility is inexplicable, and sometimes it seems deliberate. The widely available road map to Lusaka one can buy in the bookstore in the Arcades mall has advertisements scattered all around its edges that cover up the vast majority of Lusaka’s ‘peri-urban areas,’ where two-thirds of the city’s population resides (Sivaramakrishnan 1997: 229; Waste Management Unit, Lusaka City Council 2006). Many of the names of these areas appear on the map, but none of the roads that cut across and through them does. One could never use the map to navigate them. This symbolizes an invisibility that haunts a great many areas in African cities. Yet in and around this invisibility, incredibly imaginary and imaginative facets of the city emerge, creative, propulsive, innovative, and strongly linked with a wider world. As Sivaramakrishnan (1997: 229, and in Davis 2005: 37) pointed out, in Lusaka, these areas are ‘called “peri-urban” but in reality it is the city proper that is peripheral.’ In cities like Lusaka, one needs to turn one’s imagination inside out, to see the world in the city.

The paragraphs above lead me to a set of questions. What about Lusaka is actually the way many cities in Africa are, or even the way many cities in the world are becoming? What do those patterns say about the way people think about, write about, or understand cities in Africa or in the world today? As I have argued in the introduction, many major debates and theorists in urban studies bypass the continent, dismiss its cities from the cartography of urban areas that matter, banish them to minor footnotes of exception, or make of them exemplary dystopias and horror shows of future terror. What happens if we place them in the center of urban studies instead?

The postmetropolis according to Soja

In this chapter’s title, I have made a deliberate reference to the third book of Ed Soja’s trilogy of critical urban theory, Postmetropolis (2000). In this book and a related book chapter published the next year, Soja (2001: 38) uses the term postmetropolis to draw attention to ‘profound material changes’ in ‘the modern metropolis.’ He describes the restructuring, deconstruction, and reconstitution of space that he sees in cities in ‘broad brush sketches’ for a ‘multi-sided picture … of what has been happening to cities over the past thirty years’ (ibid.: 39). Soja (2000: 145–348) suggests six broad themes, which are articulated in his provocative and inventive style (he names the themes his ‘six discourses,’ on the postfordist industrial metropolis, cosmopolis, exopolis, the fractal city, the carceral city/archipelago, and simcities).

It is seldom noted in analyses of his later works that Soja began his career as a scholar of the geography of urban development in East Africa (Soja 1968, 1979; Soja and Weaver 1976). Soja started to take a much more critical stance toward modernization and modernity, but left African studies by the early 1980s. In the trilogy, Soja uses Los Angeles as his primary, though not exclusive, empirical backdrop for an engagement with a wide range of social theorists, without revisiting Africa (though he does make meaningful reference to South Africa in the more recent Seeking Spatial Justice; Soja 2010: 39–40, 84).

The first book, Postmodern Geographies, had the phrase of its subtitle, ‘the reassertion of space in critical social theory,’ as its principal aim. Drawing on his interpretation of the writings of the urban theorist Henri Lefebvre, Soja’s (1989: 80) central achievement lies in his articulation here of what he termed the ‘socio-spatial dialectic,’ whereby urban space is recast as a product of society that ‘arises from purposeful social practice.’ Soja sought to illustrate his claims along these lines in two successive chapters that close the book, entitled ‘It All Comes Together in Los Angeles’ and ‘Taking Los Angeles Apart.’ It is the latter chapter which gave inspiration to the style of this particular chapter in my book. Soja (ibid.: 223) was aiming to deploy ‘fragmentary glimpses, a freed association of reflective and interpretive field notes’ in order to ‘appreciate the specificity and uniqueness of a particularly restless geographical landscape while simultaneously seeking to extract insights at higher levels of abstraction.’ The vignettes I use below in discussing my book’s themes in relation to Lusaka are similarly fragmentary glimpses meant to convey something specific about the city but also about the more abstract themes.

It is also this more creative end of the first book which gave rise to the approach in the second, Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places (1996); but this second book is less significant for my interests here than the third book of the trilogy, Postmetropolis: Critical Studies of Cities and Regions (2000), which is structured in three parts that work to articulate each of the three dimensions of Lefebvre’s spatial triad, ‘the spatiality of human life as it is simultaneously perceived, conceived, and lived’ (ibid.: 351). My concern here is with his Part II, the ‘Six Discourses on the Postmetropolis.’

Again with Los Angeles as the empirical referent, Soja explores each of his discourses in distinct chapters. The first of these, the postfordist industrial metropolis, highlights emerging regionalism at the expense of industrial urbanism, with the formation of extended metropolitan regions built around flexible specialization production systems with the collapse of ‘fordist’ assembly-line industrialism. The second, on cosmopolis, emphasizes how globalization has changed the spatiality of power relations and society in global and world cities like Los Angeles. Exopolis gives rise to a discussion of ‘the urbanization of suburbia and the growth of Outer Cities,’ or the changed ‘geographical outcomes of the new urbanization processes’ of a ‘city turned outside-in’ (ibid.: 238, 234, 250). The fourth discourse, on the fractal city, is meant to refer to the ‘fluid, fragmented, decentered and rearranged’ social mosaic of the city through rising socio-spatial polarity, inequality, and ethnic segmentation (ibid.: 265). Soja’s final two discourses mark a bit of a departure. The carceral archipelago refers to the increasingly fortified character of urban space, via ‘privatization, policing, surveillance, governance, and design of the built environment,’ as in gated communities, homeowner associations, and the like (ibid.: 299). The final discourse focuses on ‘the restructuring of the urban imaginary’ in philosophy, urban studies, film, and computer games (ibid.: 324).

Reading through Soja’s six themes of the postmetropolis is an entertaining experience. Is it a plausible suggestion for me to simply take his discourses and do a compare-and-contrast exercise? Soja (ibid.: 154, italics in original) in fact invites us to do exactly this: ‘what will be represented here,’ he writes in the introduction to Part II of Postmetropolis (on the six discourses), ‘is an invitation to comparative analysis, to using what can be learned from Los Angeles to make practical and theoretical sense of what is happening wherever the reader may be living.’ This is, I admit, part of what this chapter is about, given my chapter title: indeed, what if the postmetropolis is Lusaka – or Luanda, or Lubumbashi, for that matter – and not Los Angeles?

One problem with such an approach is that it might perpetuate the sense that we must learn about African cities by studying Western urban theory and then applying it on the continent. Los Angeles is not necessarily a completely false start for understanding African cities – the Nigerian-Angeleno novelist Chris Abani (2009), for example, has said that LA is ‘the quintessential African city’ because he recognizes so many aspects of its social geography as more than comparable to Lagos. As I’ve noted in the introduction, there is no reason why African studies must categorically reject Western urban theory, and many authors in the recent wave of African urban studies put Lefebvre, Harvey, de Certeau, or Massey to good use. But as with these other theorists, we find that references that stretch far beyond Euro-American cities are rare in and tangential to Soja’s discussion of his six discourses. It would take some limbo dancing to finesse an African postindustrial fordist city under that discourse’s bar, if you will – though Africa’s Detroit, the Nelson Mandela Bay Municipality (Port Elizabeth-Despatch-Uitenhage) in South Africa, might perform the function if required (Port Elizabeth has a huge informal settlement called KwaFord, after all, next to Ford’s manufacturing complex). Many African cities have always been cosmopolitan, exopolitan, fractal, or carceral, but in different ways than Soja means the terms (see Murray 2008b on Johannesburg, for example). Likewise, we can say that a ‘restructuring of the urban imaginary’ is ongoing across the continent, but not necessarily owing to or coterminous with computer gaming and postmodern cyber-architecture (see Diouf 2008 on Dakar).

Soja’s latest book, Seeking Spatial Justice, picks up its narrative right where Postmetropolis ended, with the Bus Riders Union of Los Angeles. While the first half of the book is a concise and helpful restatement of his arguments over the last twenty-five years, the second half again concentrates on Los Angeles, albeit in new ways. Here, Soja makes the connections between academia and activism for social change explicit. He seeks to bridge theory and practice, to take a ‘critical spatial perspective’ into the hard work of ‘cross-cutting coalition building’ that he sees as crucial to forging more just and relational communities, cities, and urban regions (Soja 2010: 199). As with the earlier trilogy the challenge lies in dealing with the relationship between his example, Los Angeles, and cities in Africa. But the twist here is that he develops the idea of ‘spatial justice’ out of his consideration of the work of Gordon Pirie on apartheid South Africa. It stands as a stark reminder of what urban studies can gain from building from African urban studies, rather than having its directional arrows ever flowing from the North and the West into the continent.

I take inspiration from Soja’s six discourses in creating an organizing principle for the book, and in a sense a methodological approach (rather than a set of theoretical or empirical concerns per se); but I am still operating under the premise of African studies talking back to urban studies, not the other way around. What happens, I ask, if we start the discussion about ‘what has been happening to cities over the past thirty years’ from Lusaka, or any other African city, rather than LA? I choose Lusaka for many reasons, not least of which is that its very ordinariness at first glance – no grand skyline, no obvious spectacle, just a few million people living their lives in close proximity – challenges the grandiosity that often inheres to urban theory. That does not necessarily make my task of de-centering any smoother. ‘It is easy enough,’ Robinson (2006: 167) writes, ‘to raise a critique of ethnocentrism in urban studies; it’s so much harder to instigate new kinds of practices for studying cities and managing them.’ I seek to follow her lead in ‘decentering the reference points … in a spirit of attentiveness to the possibility that cities elsewhere [e.g. cities in Africa] might perhaps be different and shed stronger light on the processes being studied’ (ibid.: 168–9). In so doing, I still share Soja’s (2000: xiv) under-appreciated ‘commitment’ throughout his trilogy and Seeking Spatial Justice ‘to producing knowledge not only for its own sake but more so for its practical usefulness in changing the world for the better.’

Instead of Soja’s six themes, in this chapter and in the rest of the book, I substitute five others – with Lusaka as my touchstone city in this chapter – for an experimental vision of cities in Africa as seen through concerns with postcolonialism, informality, governance, violence, and cosmopolitanism. What has been happening to Lusaka over the past few decades? Lusaka has continued to deal with its colonial inheritance of poverty, underdevelopment, and deep inequality; the functions and forms to Lusaka’s growth contain a high degree of informality; the methods, processes, and networks for governing Lusaka have seen dramatic changes in institutional terms via democratization and neoliberalism; the city is coping with rising domestic insecurity and a variety of seeping wounds to its social fabric; and Lusaka is globalizing at a variety of scales at once. My hunch is that this bundle of phenomena speaks much more strongly to the experiences of cities in Africa over the last thirty years or so than do Soja’s six discourses. These themes are really an amalgamation and restatement of concepts developed and debated in African urban studies over the last few decades or more by many scholars in and out of Africa. They are sometimes themes that are hard to tease out from one another (particularly informality and governance), but ultimately I examine distinct phenomena under each. Since these themes provide the backbone for the next five chapters, I should note that I am merely sketching them here in this chapter in terms of how they might appear in ‘broad brush stroke...