![]()

CHAPTER 1

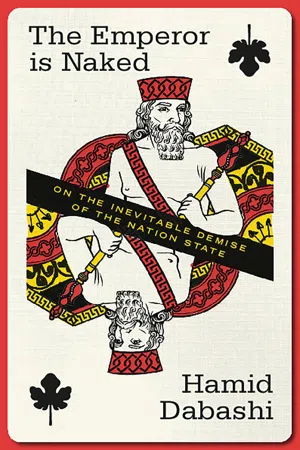

THE STORY OF THE KING WHO HAD TWO BODIES BUT NO CLOTHES

I was born and raised in Ahvaz in southern Iran at the very bosoms of a postcolonial state. The Shah of Iran, who at the time ruled over us with an iron fist, thought he was Cyrus the Great reincarnated. “Cyrus sleep in peace,” he declared solemnly one day upon the ancient Persian emperor’s grave, “for we are awake!” Using the majestic “we” assured him of the myth that his body was the body of his kingdom. “L’État, c’est moi,” he must have thought to himself in that moment in his impeccable French with Louis XIV on his agitated mind: “The state, it is me.” And the man was right. He thought he was the state. And we mortals were his mere subjects. We were sheep to him and he was our shepherd, as it were. He thought he was leading us to “the Gates of the Great Civilization.”

The lived experiences of my generation of Iranians embrace two monarchical dynasties and a third Islamic Republic. Ahmad Shah Qajar (reigned 1909–1925) was still in power when my parents were born and raised in southern Iran. They grew up to adulthood and married in Ahvaz, and my mother gave birth to my older brother Majid, may they all rest in peace, during the reign of the first Pahlavi monarch, Reza Shah (reigned 1925–1941), while I was born and raised during the reign of the second and last Pahlavi monarch, Mohammad Reza Shah (reigned 1941–1979), and I was a graduate student doing my doctoral degree at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia when Ayatollah Khomeini (reigned 1979–1989) led the revolution that toppled the last Pahlavi monarch. In my own and my parents’ lifetimes, therefore, two dynasties and a subsequent Islamic Republic pretty much exhausted the binary possibilities of two versions of state formations that could follow the ravaging colonial experiences of Iran during the nineteenth century.

This, though, was not all. Soon after my birth in this postcolonial state, on 15 June 1951, the most traumatic event of my generation occurred when our “Crowned Father,” as we were told to call our king, would run away to Europe in August 1953, fearing for his life after a vastly popular uprising led by our democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh threatened his monarchy. The CIA and MI6 staged a military coup and brought him back to power. All of this was Greek to my emerging Persian, of course.

The myth of the postcolonial state and all the havoc that myth has visited upon my homeland and beyond, throughout Asia, Africa, and Latin America, dwell in our lived experiences, where the mortal lives of our monarchs and mullahs were staged and enshrined in a mythology of power and glory, while the fact of the matter was they were all entirely stripped of any such claim to legitimacy, that they were indeed naked, shorn of any shred of democratic basis to their politics. The harder these ruling regimes of power tried to manufacture a staged legitimacy for themselves, the more naked and devoid of meaning were their claims to any such democratic representations. At the height of his power in 1971, the Shah of Iran celebrated 2,500 years of Persian monarchy, with the same pomp and ceremony that the mullarchy that succeeded him staged Shi’a martyrology to manufacture consent to their equally illegitimate rule. One appealed to Cyrus the Great and the other to Prophet Muhammad, and then to his son-in-law Ali and his male descendent, particularly to the Imam Hussein. They were all delusional—manufacturing a whole parade of imaginative operatic stage to mere shreds of historical evidence. They were all convincing themselves in power and fooled none except those who were the beneficiaries of their delusions.

As I grew older, I thought all decent people wore clothes in public. I had no clue that kings had two bodies, or that our particularly vainglorious kings and mullahs had no clothes on at all. The myth of the postcolonial state is already evident in the famous Danish author Hans Christian Andersen’s splendid story “The Emperor’s New Clothes” (1837), where we encounter a narcissistic king not too dissimilar to our own Shah of Iran, or Ayatollah Khomeini who toppled him:

I could not possibly put it any better: both the Shah of Iran and the ayatollahs who toppled him were all “sitting in their wardrobes.” And we were supposed to assume them properly clothed in auras of power, authority, and legitimacy. They were not. They were all naked, and they looked quite ridiculous.

THE BODY OF THE SOVEREIGN

Years later, when I graduated from reading children’s fables and began reading adults’ books, I would read and learn about this proverbial king’s (and in our case mullah’s) no less than two bodies. Now we had a king who had two bodies but no clothes on. If we were to follow the European medieval metaphor of the body of the sovereign as corporeal evidence of the state (we do not have to, but just for the sake of argument for now) he or she ruled, with the crown standing for the head and the body for the totality of the polity, the term “body politic” (the political body of society) derives from the concept of the king’s two bodies first noted by the prominent historian of the Middle Ages Ernst Kantorowicz, as a point of theology as much as of statehood. In The King’s Two Bodies (1957), Ernst Kantorowicz (1895–1963) wrote on medieval ideologies of the state with uncommon insights—all of which, of course, about Europe and Christianity. In the context of the European medieval political theology, Kantorowicz addresses the historical problem posed by the “king’s two bodies”—the body politic and the body natural; while the physical body dies the symbolic body persists and guarantees the longevity of the throne upon which he or she sat, and thus of the dynasty he represented, and therefore of the state he ruled. Thus, the body politic assumes a reality sui generis. The political theology of the Christian monarch in effect underlies his mortal body and immortal presence. In effect, modern theories of state power and legitimacy emerged from that Christian disposition of the body of the monarch, thus theorized and immortalized within the European framework of statecraft.

The central idea of Kantorowicz comes from a source addressing legality and sovereignty, in which we learn:

The “Nonage” of the sovereign is therefore the point where the political power of the ruling monarch becomes transcendental to itself and transient beyond itself—linking his mortal body to his immortal allegory of power. “The Imbecility of Infancy or old Age” are both the occasions where the body of the king resides but his power and authority do not—based on which presuppositions we conclude: “his Body politic is a Body that cannot be seen or handled.” This notion of the king’s two bodies, rooted in Christian theological imaginary and at the root of European dynastic sovereignty, is then transmitted through the structural violence of colonialism into the rest of the non-European and non-Christian (and non-dynastic) worlds—and because it comes from a position of power and hegemony, it becomes universally valid.

It was at this point that I was reminded of the famous story of “The Emperor’s New Clothes” by Hans Christian Andersen, where we learn about two charlatan tailors who promise a vainglorious emperor a suit that will appear invisible to those around him who are unfit for their positions, while in reality they make no clothes at all. When the emperor parades before his subjects in these imaginary clothes, no one dares to utter a word and say that the emperor is butt naked for fear of exposing themselves. Finally, a child cries out, “But he isn’t wearing anything at all!” Particularly important for me in this story was this splendid passage:

Here, I felt precisely like that little child, noticing the fact that the postcolonial state, rooted in Christian theology and the byproduct of European colonialism, lacks any legitimacy whatsoever outside its European genealogy, and the adults in the room, as it were, pretending it does were in fact implicated in the sham. European colonialism to me are those charlatan tailors, the courtiers all the postcolonial states, the natives who have assumed power as if their state had any relations whatsoever with the notions they thus claimed. It was quite a charade.

WHEN THE REST RISES

In the Spanish version of Hans Christian Andersen’s story, which is probably its origin, the figure of the little boy is given as a slave a black man who, unlike the rest of the royal subjects, is not afraid of being accused to be a bastard if he did not see the invisible (nonexistent) clothes:

Based on this version of the story from Libro de los ejemplos (1335), the Spanish collection of fifty-one cautionary tales by Juan Manuel, Prince of Villena (1282–1340), the truthful slave is harassed, tortured, and abused for seeing and telling the truth:

This earlier version with a daring black slave as its protagonist is in fact far more powerful and poignant than its lighter version in Hans Christian Andersen. The black man is an infinitely more critical character in this version to lead us to think more critically about the delusional spectacle of state as the supreme hypocrisy of our age.

In the book I am about to write, I wish to take these preliminary thoughts and make the following argument: the very notion of the “nation-state,” as we understand it today, was a colonial legacy and has now transformed into a postcolonial myth. We in the postcolonial world had no business buying into it. It has never worked—in or out of Europe. Look at the mess of Brexit or the constant menace of separatist movements from one end of Europe to another. It has in fact created subnational categories of resentment and supranational geopolitics of aggression and violence. The result is the transformation of the illusion of a legitimate state into the reality of a total state predicated on pure illegitimate violence. The perfect model and blueprint of this reality is Israel, a total state with no real nation, dominating Palestine, an organic nation with no real state. The so-called Islamic State (Daesh), an entirely dangerous delusion, is another perfect example of the total state, a state with no nation, a self-delusional caliphate, the summation of all the other illegitimate states from one end of the Arab and Muslim world to the next. We might offer Saudi Arabia as another perfect example of this total state. For Saudi Arabia, named after Ibn Saud (1875–1953), the so-called “founder” of the state, names the entire fictitious “nation” under its rule as “Saudis” too. In other words, all the manufactured citizens of this colonial concoction and postcolonial state are the mini-models of the total and final state—not peoples, but cloned mini-states. Politics as such, therefore, has moved into two opposite directions: the metanarrative of geostrategic alliances of the region and micropolitics of domestic constituencies—such as labor, gender, or most urgently the environment. This also means the end of the very geographical supposition of the “nation-state,” again as we have inherited it from our colonial period, for at this moment, at the writing of these words, the hand of every state is in another country’s pocket. Turkey is in Syria and Iraq. Saudi Ar...