![]()

ONE

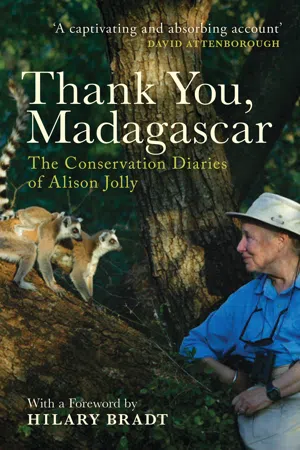

‘Our country is committing suicide’

In Madagascar, wide-eyed lemurs offer insights into humanity’s deep past. Swivel-eyed chameleons flag their emotions in scarlet and emerald and indigo blue. Lemon-yellow luna moths escape their predators by falling from the treetops like drifting leaves. A spider spins golden silk which can be woven to create a cape worthy of a Malagasy queen. In the forests of this island-continent, almost 90 percent of species are endemic, unique to Madagascar. It is an alternate world of evolution.

However, if its forest destruction continues, we could be left with only lemurs confined to zoos and the rarest palms and baobabs in botanic gardens and seed banks. The Malagasy golden-silk spider is endemic of course—not rare, but only a handful of humans know how to spin its silk. Conservationists like myself believe that the living ecosystems of Madagascar are a world heritage in the truest sense: a treasury of beauty, science and wonder for the entire world—and that keeping these ecosystems and their species alive is a responsibility for the world.1

At the heart of this tale is the conflict between three different views of nature. Is the treasure-house of Madagascar, with its beauty and evolved fascination, really a heritage of the world? But what about the people who live beside those forests, and depend on their bounty? Is it instead a legacy of those people’s ancestors, bequeathed as a sacred legacy to serve the needs of their living descendants? Or else is it an economic resource to pillage for short-term gain or to preserve in the longer term only for its return in ‘environmental services’? The three attitudes—aesthetic, traditional and economic—collide throughout this book.

Thank you, Madagascar is an eyewitness account of a major case study in the politics of conservation. I argue that in spite of the irritations or even fury of the people on all sides of the story, Madagascar must save its heritage. In spite of being the world’s tenth poorest country, in spite of having at the moment a government which does not govern, in spite of being a political football dribbled in any direction by foreigners offering cash or in pursuit of cash, Madagascar is one of the glorious places. Not just the forested semi-natural environment, but its cultures.

Madagascar is a blend of African, Indonesian and Arab backgrounds that dates back well over a thousand years.2 The Indo-Polynesian tongue is studded with Bantu words, different in the differing dialects. Music ranges from plaintive polyphonic strings to African rhythms of drums and stamping heels. As in most countries, there are splits which translate to differences between people at the center and the periphery, darker people and lighter people, rural people and those in the towns. Malagasy are justly proud of their complicated nation—but not all know that the nation needs its environment to survive. Sustainable development for both people and natural environment is the only worthwhile goal. Madagascar may fail, sinking ever deeper into poverty and degradation, but the stakes are so high that it ought, somehow, to win.

The book is not a polemic. It is a story. In 1985 I watched a breakthrough: a moment when national politics and foreign funding came together. Now I knew I was eyewitness to conservation history. So I wrote it down. I scribbled in airplanes, on hotel tables, in tents under the mosquito netting. I have drastically cut and excerpted and added a few explanatory phrases, but the diaries are what I saw and felt at the time. (The original notebooks, twice as long, are stored in the Cornell University Library archive.) If my style seems a bit too literary, actually I always write like this—at least ever since my long letters home to my parents at the age of 25 when I first discovered Madagascar as a magical world. The adventure tales of my childhood paled beside adventure I could live: with people, with landscape, with lemurs!3

I thought these diaries couldn’t be published for twenty years or so until my friends were old and gray and would not care what I said about them. Twenty years have more than passed. My friends are old and gray and feistier than ever. Now I think it is time to tell you my story of a time when conservationists thought we could save the world—or at least Madagascar.

I arrived in Madagascar in 1962 as a stunningly ignorant Yale Ph.D. Like others of my kind I was single-minded: I wanted to watch lemurs, not people. Besides, I was in love. I hoped to get married and live happily ever after, far from Madagascar—if only Richard Jolly would make up his mind to propose! Richard was and is an economist who actually likes people.

I wrote up my fieldwork, but I was soon prevented from undertaking further field study by the arrival of our four children. I pottered away in England writing second-hand science. I fretted over my distance from Madagascar, but I didn’t have a chance to return until 1970 for the first of four international conferences that anchor the story of this book: 1970, 1985, 1998, and one happening as I write in 2013. The 1970 conference was ‘Malagasy Nature, World Heritage’.4

Jean-Jacques Petter and Monique Pariente organized that meeting. Jean-Jacques and his wife Arlette, both from the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, had done the only detailed study of lemur ecology and behavior that preceded my own. Monique Pariente was almost ridiculously well connected. Her father, General Gabriel Ramanantsoa, would become the country’s president in circumstances no one foresaw in 1970.5

We met in the national university, poised on its pleasant hilltop. The view in one direction embraced the capital city, Antananarivo, its skyline culminating in pre-colonial royal palaces. The opposite view opened to a panorama of rolling hills clothed in dry golden grass ready for annual burning. Cupped in the valleys glowed green rice paddies. Gardens of pink hibiscus and orange marigolds softened the concrete university buildings.

France had colonized Madagascar as late as 1895. The country achieved independence in 1960. French policies lived on. The forests were declared to belong to the nation. Forestry action attempted to suppress indigenous slash-and-burn, called tavy, both to promote French commercial interests and to save what French scientists had long recognized as extraordinary natural heritage. Madagascar boasted some of the first nature reserves in the whole African region, established from 1927. A lovely zoo, a botanical garden and a research institute in the capital itself also dated from 1927, encircling a traditional sacred lake. In 1970 there were still many French scientists and Frenchmen behind government office doors, two hundred of them on the staff of President Tsiranana alone. The French ambassador, not the Malagasy president, lived in the ex-governor general’s palace. The splendid new university was still the Université Charles de Gaulle.6

Richard had the idea of a joint paper for me to present at the conference ‘Conservation: Who Benefits and Who Pays?’ In the short term, we said, tourists and tour companies benefit from national parks, while peasants lose rights to their land. A banal thought, nowadays, but the reaction then was interesting. The stars of the conference surged up on either side of me: the solo transatlantic aviator Charles Lindberg, then president of the World Wildlife Fund, and Sir Peter Scott, the great ornithologist and artist, who drew WWF’s Panda logo. They marched me out into the university gardens for discreet reproof. ‘Of course we know what you say is true, but this is not the time to say it. We have only just convinced East Africa to promote their own national parks. We don’t want them getting the wrong idea. Don’t stir up trouble.’ I was too overawed to protest.

Then, no sooner inside again than Perez Olindo, head of the Kenyan Game Department, and David Wasawo, soon to be president of the University of Dar es Salaam, loomed up on either side of me in turn. They marched me back round the gardens, out among the marigolds. ‘High time somebody said that!’ they exclaimed. ‘Come and stay with our families in Nairobi!’ Somehow someone left that paper out of the published conference proceedings.7

Meanwhile, trouble was brewing—particularly among the students privileged to study in the Université Charles de Gaulle. In 1972 they erupted into violence. They wanted the University nationalized. They wanted jobs on graduation, not Frenchmen standing in their way. Student mobs ruled the streets of Antananarivo. The town hall burned down. The cavity left by its blackened carcass remained on the Avenue de l’Indépendence for almost four decades. Monique Pariente’s father, General Ramanantsoa, became temporary president, followed in 1975 by the hardline socialist Richard Ratsimandrava. Ratsimandrava was assassinated after nine days’ rule. The state council then elected the almost equally socialist frigate captain Didier Ratsiraka.

Ratsiraka hoped to become a famously idealistic francophone Nyerere. Instead, socialism did not work in Madagascar. There were many reasons, external as much as internal. In 1982 the IMF and the World Bank took over the bankrupt state. They imposed harsh ‘structural adjustment’: what today we would call ‘austerity’. The economy slid further and further into depression.

A meeting in Jersey in 1983, hosted by Gerald and Lee Durrell, began the cumbersome process of reopening research visas. It was there that Jean-Jacques Petter suggested a second great conference. WWF International had appointed his protégé Barthélémy Vaohita as their representative. Barthélémy had a huge mandate: to see to the beginnings of on-the-ground WWF programs, right down to finding spark plugs for a donated motorboat. Anglo-Saxons doubted his abilities in practical matters. Now he had a task he could do brilliantly as perhaps the only Malagasy naturalist who would intervene politically. In 1984 he convinced every minister to sign a declaration in favor of sustainable development. The government of the time finally realized it had just one new fishhook for foreign aid. The bait? Lemurs! Chameleons! Biodiversity! Never mind that their own biodiversity was a side issue to almost every Malagasy, except as it could be harvested or eaten. Somehow the rich foreigners were obsessed with it—and would pay.8

So the next great conference arrived in 1985. This time it was ‘Madagascar: Conservation and Sustainable Development’. Five hundred civil servants from the provinces were summoned to the capital to hear about the new policy. Donors and politicians figured far larger in the mix than scientists. The president of WWF was honorary chair: Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, husband of the British Queen. The assembly waited much more eagerly for Kim Jaycox, vice president of the World Bank.

For ten years, from 1975 to 1985, the xenophobic Ratsiraka government had kept out foreign conservationists. Now we were back with a new mandate and a hope of actual funds. It was perfect timing. The World Bank had royally messed up in the Amazon. Protesters hung bloody banners opposite its Washington buildings: The Bank Murders Rainforests! Madagascar offered itself as a virgin country, or at least one unharassed by biologists for the previous ten years. Hooray for a country where the environmentalists might this time get things right.

My diaries begin…

October 25, 1985. Free Day! (Giggle).

Madagascar wins again versus American can-do! Wonderful Madame Berthe Rakotosamimanana has organized a one-day meeting of us scientists before the main Congress. This in the Solimotel, a new hostelry downtown. I used to call Mme Berthe the Tiger of Tananarive when part of her job was refusing research visas to foreigners. Then last year she turned up at Jersey Zoo, invited by Gerry and Lee Durrell. She and Barthélémy Vaohita of WWF and Joelina Ratsirarson of Water and Forests and a bunch of us scientists all brokered a cumbersome agreement to let foreign research back in. At the end Mme Berthe’s round face was wreathed in round smiles. I realize this is what she’d hoped all along.

Anyhow today she came out in her true colors as Prof. of Paleontology. Russell Mittermeier, VP of the World Wildlife Fund, was to lead off the science conference. He does not trust Madagascar’s te...