![]()

WRITING A DIFFERENT STORY: BIGGER THAN THE FACTS AND ITS TRANSLATION

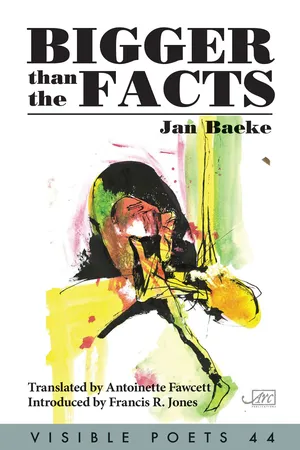

JAN BAEKE

Since his debut collection in 1997, the Netherlands poet Jan Baeke has published eight books of poems. These have gained him critical praise and widespread respect at home, but also increasing attention abroad. The present volume, Bigger than the Facts, is a translation of Baeke’s fourth book: Groter dan de feiten (2007). This was shortlisted for the 2008 VSB Poetry Prize – one of the Netherlands’ two top awards for a stand-alone collection. And in 2016, Baeke won the other top award, the Jan Campert Prize, for Seizoensroddel (Season’s Gossip, 2015).

Baeke’s poetic and literary activities are not limited to writing his own poems. He has translated English poet Lavinia Greenlaw, Scottish poet Liz Lochhead, Welsh poet Deryn Rees-Jones and US poet Russell Edson into Dutch. Since 2011 he has co-curated the programme of Poetry International Rotterdam, the Netherlands’ biggest poetry festival and a key fixture in the world poetry calendar. And for several years, he chaired the Management Committee of the Vereniging van Letterkundigen, the Dutch Writers’ Guild.

Jan Baeke’s CV also has a strong film element – unsurprisingly, perhaps, for someone whose poetic vision is so cinematic. Before moving to Poetry International, he worked at the Dutch Film Museum in Amsterdam. Here, for example, he initiated and curated 35 mm POEM, a series of events combining silent film with live spoken poetry. And since 2006 Baeke has collaborated with Alfred Marseille on the poetry-film venture Public Thought. Their 2017 English-language short about the refugee crisis, At the Border (http://www.publicthought.net/attheborder.html), for example, combines archive and specially-shot clips with news voiceovers and on-screen poems by Baeke.

POEM WORLDS

As we read a work of literature, the flow of words condenses into images. These combine in turn to form a ‘text world’, which surrounds us while the reading lasts, and sometimes for long afterwards. A world with its own landscape, objects and beings, peopled with characters who act, feel, think and dream. So what text world does Jan Baeke build for us in Bigger than the Facts?

Baeke says that the poems in this book “are always about something, they refer to reality”.1 But how its world works is not immediately plain to see. At least on the surface, many poems appear hermetic, even surreal. Yet elements keep recurring, coalescing little by little into dreamlike leitmotifs and sub-narratives. A bus journey. A hotel room beside a square. Dogs. A you-figure who smokes. A he-figure – perhaps the narrator in the you-figure’s eyes, perhaps someone else. A blind man. And a canary – a character important enough to be depicted on the Dutch edition’s cover.

This slow layering of leitmotifs reminds us of films by Tarkovsky or Buñuel. It is no coincidence that these two directors top and tail the long list of inspirers cited at the end of the book: modernist poets and prose writers, but also filmmakers. Buñuel in particular is a master of montage. Baeke claims that this technique, where “as a reader you have to make the links between the various images yourself”, is the main way in which film influences his poetry.2

But if this book’s world is dreamlike, perhaps we should enter it as we experience a dream. Intuitively, with minds open to whatever twists and turns it might bring. Katleen Gabriëls, reviewing this collection,3 explains that its rules become clearer at whole-book than at individual-poem level:

As a reader you’re admitted to an intimate event. Yet you’re kept at arm’s length, because the poetry pins nothing down and many elements remain open. The poems per se only come into their own as a whole. Then a created world opens up – one which you want to follow closely.

From this broader viewpoint, Bigger than the Facts appears to relate a story, from summer till winter, of a relationship between two people who separate and finally seem to be reconciled. In Baeke’s words,

Love so often doesn’t work out, it’s hard for people to be and stay together. On the other hand, we’re also drawn together. It’s a theme that has always interested me: what keeps people together, what drives them apart again? What do people expect from life, or more generally: what do people expect from reality and how does one’s relationship with another fit into that?

Or, as the book’s closing lines say: “This is a question about / love or about / a man who walks into a hotel. // What is it that I want to tell you?” (‘I Invented Him: 13’).

The book seems set in Southern Europe, at a time of war or occupation. In the opening cycle, a couple travel by bus to a strange city, and book into a hotel by a square where the barman is “listening to messages for the resistance” (‘Only the Beginning Counts: 2’). Filmically, the poems focus on the sensed, seen moment. But the seer knows that this moment will pass, presaging a later loss: “to be a lover for the smoke. / When will it all be ash and not as now, darkness / that I can see, in your eyes, above the sun of your cigarette” (epigraph poem).

In the next cycle, we learn that it is summer. In its debilitating heat, the middle-aged narrator’s body “has begun / to make new and useless flesh” (‘Summer’s Way: 2’). A dog makes its first appearance. Then the you-figure leaves the narrator: “It was inevitable […] that you got up hours later / that I didn’t realize you had long departed” (‘What Couldn’t be Otherwise: 7’). Summer has seemingly now turned to winter, though the narrator is still in the hotel and the city. More dogs appear. As does the he-figure – who then leaves, and whose name is sought on lists of the dead (‘I Invented Him: 9’). Finally, the you-figure returns, seemingly injured: “I want you to find these lines / and understand that you’re my life” (‘I Invented Him: 10’).

Yet there is more to Jan Baeke’s poetic worlds than their surface narrative. Piet Gerbrandy describes Baeke’s wider work as “a quest for language and meaning”.4 Or, as Thomas Möhlmann puts it, “in his search for coherency or at least some grip on reality, Baeke shows us just how uncertain, incoherent and unpredictable the world around us actually is”.5 As for Bigger than the Facts, Edwin Fagel writes that it reveals “what lies, or could lie, behind the facts”. In it, Baeke shows us “the contingent nature of reality” and “its ambiguity”: the fact “that what we see doesn’t exist in that way”.6

WRITING

The collection’s narrative style, with montaged scenes loosely interwoven with leitmotivs, arises partly from Baeke’s poetry-writing processes. Baeke says that he started by writing individual poems. Elements, like the canary, began recurring by chance, but soon gained their own momentum, generating a sense that there was “a cycle in there”. Then, he tells the interviewer,

two people hove into view. I started thinking […]: what kind of people are they, what moves them? And so a kind of narrative line emerged […]. There’s a man, there’s a woman. They relate to each other in a certain way, perhaps share a history and break up at one point. What brought them together and drove them apart again? I found that interesting to investigate.

This encouraged him to write “as many poems as possible to see what story would emerge”, and then to weave these and the earlier poems into a narrative. Finally, he filled in any gaps in the development of the characters and their relationship.

Composing the poems, therefore, did not simply consist of writing out a set of ideas. In Baeke’s words, “Perception and language influence each other. Language is a way to get a grip on perceived reality.” This explains why some poems are more representational, where language serves to communicate events and images seemingly already in the poet’s mind. But also why the events and images in other poems seem to be generated by language itself. In the latter case, Baeke is following a tradition in Dutch poetry since the 1960s, pioneered by poets such as Hans Faverey. Here the poem is almost a Ding an sich, a self-sufficient entity, rather than a representation of something else: “The impassive endures. / No stone feels delight. / Insects tap and tap inside a lampshade” (‘Summer’s Way: 11’).

Sometimes, however, the images simply ...