![]()

1

Sculpture and the decorative

Towards a more integrated mode of art history writing

Imogen Hart and Claire Jones

This collection asks us to consider what an art history that works across object categories and artistic disciplines might look like. It focuses on the intersection of sculpture and the decorative, but its argument is pertinent to art history more broadly. In providing an opportunity for two apparently separate areas of making – one ‘high’, one ‘low’ – to shed light on one another, and for their respective fields of scholarship to interweave, the volume will, we hope, offer a model for a more integrated mode of art history writing that embraces the complex multivalence of objects. Foregrounding the overlaps between sculpture and the decorative not only demands a reassessment of the ways in which the two fields have been defined and separated but also expands the scope of art-historical practice to incorporate hitherto neglected objects deemed too decorative for the study of sculpture or too sculptural for the study of the decorative. Bringing to centre stage objects, makers and spaces that have been marginalized by the enforcement of boundaries within art and design discourse, the volume challenges the classed, raced and gendered categories that have structured the histories and languages of art and its making.

Sculpture and the Decorative aims to make two distinct contributions to the scholarship. First, it considers sculpture and the decorative arts together, prioritizing neither, in contrast to the main literature on sculpture and on decorative art, each of which usually refers to the other only in passing or as a detour. And although sculpture appears first in our title, we are not only concerned with expanding approaches to sculpture through the lens of the decorative but also committed to exploring how the sculptural sheds light on the decorative. Claire Jones has argued elsewhere that ‘the history of sculpture must make room for the decorative arts’, and here we add the demand that the history of the decorative arts must make room for sculpture.1

Second, the volume analyses critically the theoretical issues at stake in examining the relationship between sculpture and the decorative, from both historic and present-day perspectives. Our contributors consider how the criticism and histories of sculpture and the decorative have been written. As Grace Lees-Maffei and Linda Sandino have stated elsewhere, to understand the relationship between the fine and decorative arts we need to consider not only ‘the artefacts themselves as hybrid practice’ but also ‘the reception of those artefacts’.2 Our contributors chart the ways in which the terminology and concepts associated with sculpture and the decorative have been employed and negotiated by practitioners, critics, audiences and historians in different contexts. Most importantly, they explore why these categories have been constructed, promoted, contested and dismantled, helping us to understand the various agendas that the shifting relationships between sculpture and the decorative expose and serve to support. ‘Decorative’ is not simply a descriptive term; it is an evaluative one, often with negative associations. As Julia Kelly puts it, ‘To be “decorative” is to be instantly marginalized as not serious: a luxury or indulgence rather than an integral part of society’s cultural, economic or political functions and processes.’3 This volume sets out to challenge such assumptions.

* * *

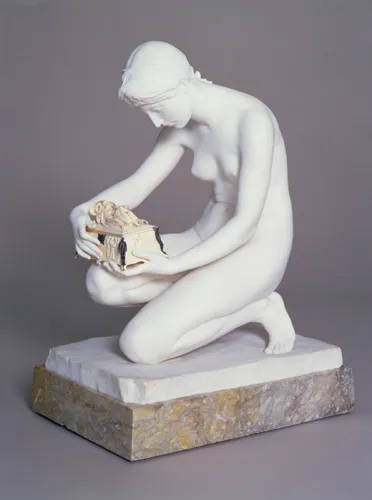

The interrelationship of sculpture and the decorative is predicated on a hierarchical imbalance. In most art academies, sculpture is a member of the hallowed trinity designated the ‘fine arts’, alongside painting and architecture. The ‘decorative arts’ is a fourth, outsider category, encompassing all the arts that are not ‘fine’.4 As one of the ‘fine’ arts, therefore, sculpture’s artistic value is conventionally held to be higher than that of the decorative arts. Sculpture, in turn, has often been considered inferior to painting and architecture.5 As the late Benedict Read observed, ‘Histories of the Royal Academy [London], particularly the more recent, have been remarkably silent about the role of sculpture.’6 The need to assert sculpture’s fine art status, even within the academic triumvirate, may partly explain why sculptors and sculpture studies have downplayed sculpture’s relationship with the decorative.7 The term ‘sculpture’ is singular, implying a unifying essence that all objects deemed to be sculpture share, whereas the ‘decorative arts’ are multiple and diverse, while also retaining a somewhat undefined commonality. Sculpture is therefore a more selective category. Despite the fact that as a term it has proved itself extraordinarily flexible, spreading into an ‘expanded field’ in the late twentieth century, its structural integrity as an organizing concept and its perceived value as a label that tells us something about an object remain secure.8 ‘Is it sculpture?’ remains a valid question. An object’s questionable status as sculpture usually arises from its association with elements more commonly connected to the decorative.9 Such problematically decorative aspects of sculpture include polychromy (as opposed to white marble), the small scale of the statuette (as opposed to life-size or monumental figures) and the integration of multiple materials, as, for example, in the ivory and bronze casket Harry Bates crafted for his marble figure of Pandora (Figure 1.1).10

Figure 1.1 Harry Bates (1850–99), Pandora, exhibited 1891. Marble, ivory and bronze on marble base. 106 × 54 × 78.5 cm. © Tate, London 2019.

It is much more difficult to imagine an animated discussion over whether an object should be admitted to the category of the ‘decorative arts’, which is inherently more imprecise and inclusive. Historically, the decorative arts have been most frequently defined in opposition to the fine arts, as practices and objects that do not meet the latter’s elevated criteria, rather than as holding any specifically determined qualities.11 The decorative eludes definition, but the term is often used as though its meaning were self-evident. Its ambiguity is further intensified by the fact that the adjective ‘decorative’ can also be applied to a work of fine art – a ‘decorative sculpture’ or a ‘decorative painting’.

The label ‘decorative’ is thus unstable. It is often employed when a sculpture or painting is designed for or placed in the context of another object, as in fine art sculpture reduced in scale to form part of a clock garniture or a history painting repainted on a commemorative vase. It can also refer to a work’s relationship with the built environment. As Alex Potts points out, sculpture has often been ‘installed more decoratively’ than painting, pointing to the potential of the context of display to frame an object or group of objects as decorative.12 Because sculpture and decorative art have such a strong conceptual and physical relationship with the spaces in which they are displayed, many of our contributors focus their attention on specific locations in which sculpture and the decorative have come together. While some of the objects discussed were made with an exhibition or museum context in mind, others were produced to fulfil the particular functional and symbolic requirements of their makers, patrons and viewers in a range of settings, from ships to spaces of civic ritual, worship and commemoration.

Another common meaning of the term ‘decorative’ is the characteristic of being formally elaborate. These two meanings often coincide. Statuettes, as Martina Droth notes, ‘fall somewhere between the two’.13 Other more canonical objects share this condition of double decorativeness; for instance, most of the examples in Michael Baxandall’s The Limewood Sculptors of Renaissance Germany are both incorporated within architectural schemes and visually intricate.14 In addition, the term ‘decorative’ can refer to objects with a function, such as urns, some of which might be also described as sculpture, whether because they feature a sculpted figure, because the treatment of the material is strikingly sculptural, or because they are associated with a specific sculptor.

An important element of the relationship between sculpture and the decorative is their often-shared three-dimensionality. Because of this, both sculpture and many of the objects grouped together under ‘the decorative arts’ resist being understood as an ‘image’ in the ways that painting has been, and both are as much bound up with material culture as with visual culture. Margit Thøfner engages with this issue in Chapter 2, arguing that ‘the category “visual culture” is simply not sufficient for understanding Lutheran sculpture. It must be expanded to encompass the spatial and the sonic.’ Her study of a seventeenth-century Danish altarpiece reveals the interplay between sculpture and music and challenges the hierarchy of figuration and ornament. Thøfner draws a fascinating parallel between sculpted biblical narrative and musical melody, both of which are animated by an ‘exuberantly rich ornamental framework’ – the carved decoration of the altarpiece and the polyphonic setting. Thøfner shows how the decorative context – a liturgical, multisensory environment – invests the decorative forms of this sculpture – i ts ornamental passages – with rich meaning. Far from being merely superficial, the decorative is an integral part of the sculpture. Thøfner’s chapter exemplifies our contributors’ shared commitment to exploring the conceptual complexity of the decorative.

Bearing the diverse meanings of ‘sculpture’ and the ‘decorative’ in mind, this book proposes that they be understood not as two distinct fields that have much in common but rather as two overlapping, malleable concepts.15 We are aware that this is a polemical position that some readers may object to – those, for example, who are invested in sculpture as a discrete realm of practice, or those for whom craft represents a position from which to critique the art world.16 We certainly do not advocate collapsing sculpture and the decorative together and acknowledge that there are situations (historical and current) when sculpture and the decorative might be productively understood as separate categories. Nevertheless, we persist in asserting that there is no rigid distinction between sculpture and the decorative. As we hope this book will demonstrate, both historically and in contemporary practice cross-fertilizations between sculpture and the decorative have played a vital role in processes of production and conditions of display, bringing sculptors into contact with diverse makers, materials, techniques, forms, colours, ornament, scales, styles, patrons, audiences and subject matter.

* * *

Chronologically, the book begins in the mid-seventeenth century with Margit Thøfner’s chapter, continues with seven chapters on the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and concludes with three chapters focused on contemporary practice. That is not to say that the eighteenth century is entirely absent. An important source of inspiration for the project was the e...