Every Place Matters

Towards Effective Place-Based Policy

- 80 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Every Place Matters

Towards Effective Place-Based Policy

About this book

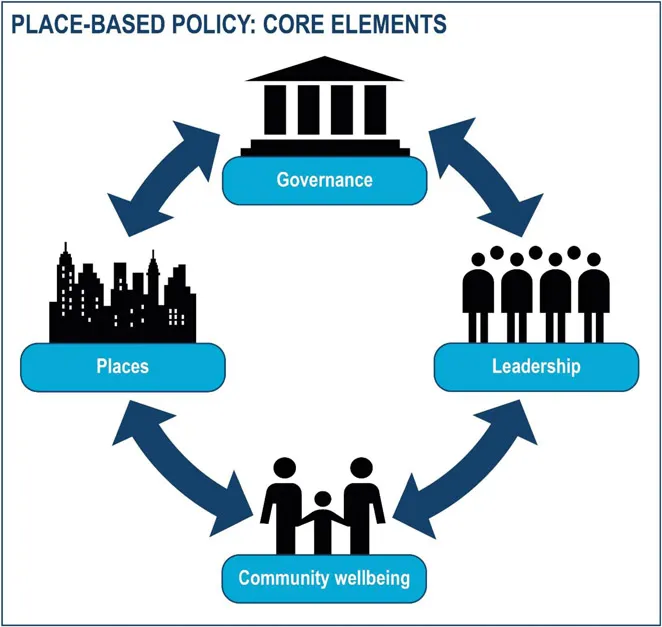

Across the globe policy makers implement, and academics teach and undertake research upon, place-based policy. But what is place-based policy, what does it aspire to achieve, what are the benefits of place-based approaches relative to other forms of policy, and what are the key determinants of success for this type of government intervention? This Policy Expo examines these questions, reviewing the literature and the experience of places and their governments around the world. We find place-based policies are essential in contemporary economies, providing solutions to otherwise intractable challenges such as the long-term decline of cities and regions. For those working in public sector agencies the success or failure of place-based policies is largely attributable to governance arrangements, but for researchers the community that is the subject of this policy effort, and its leadership, determines outcomes. This Policy Expo explores the differing perspectives on place-based policy and maps out the essential components of effective and impactful actions by government at the scale of individual places.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1.

WHAT IS PLACE-BASED POLICY?

1.1 INTRODUCTION

WHAT IS PLACE-BASED POLICY?

- Coordination of challenges

- Multiple levels of governance

- Collective public good

- Complex policy

- Smart specialisation

- Place leadership

- Shared leadership

- Consensus

- Cross-boundary

- Shared goal

- Community aims

- Co-design

- Social networks

- Social capital

- Links between actors

- Individual agency

- Local institutions

- Alan Scott showed how individual cities and regions can shape national economic growth through their influence on individual technologies.6

- Paul Krugman established ‘the new economic geography’ and showed the ways in which cities and regions linked trade to economic growth.7

- Michael Porter demonstrated how clusters of locally based industries were a driving force in national economies.8

- Ed Glaeser and colleagues set out how the characteristics of individual cities shape growth.9

- Adam Jaffe and colleagues articulated the important role of knowledge spillovers and exchange as a determinant of growth.10

1.2 DEFINING PLACE

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preamble

- Authors

- Executive Summary

- Key Recommendations

- 1. What is Place-Based Policy?

- 2. What are the Benefits of Place-Based Policy?

- 3. Requirements and Challenges of Place-Based Policy

- 4. Outcomes of Place-Based Policy: What Works and What Does Not?

- 5. Conclusions: Questions Answered, Issues Remaining

- Glossary

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app