This is a test

- 164 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Rise of Hotel Chains in the United States, 1896-1980

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This title combines history, organizational theory and statistical analysis to examine how chains have come to dominate the hotel industry over the past century. It provides information and insight not only on a major American industry, but also on the rise of chains - a phenomenon increasingly affecting many other industries.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Rise of Hotel Chains in the United States, 1896-1980 by Paul L. Ingram in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1

The Rise of Organizational Forms

This book describes a transformation in the form of organization in the hospitality industry. Traditionally, that industry consisted of owner-operated organizations. During the twentieth centuiy hotel chains, which are professionally managed, multi-unit organizations, have risen to prominence. The rise of hotel chains is a significant development for participants and customers of the hospitality industry, and for students of organizations and the American economy. The decline in importance of independent hotels represented an end to a way of life for small town hoteliers. The rise of hotel chains caused new patterns of competition among hospitality organizations and created new opportunities for employees in the hospitality industry by necessitating a range of managenal roles that did not exist for independent hotels. Chains also allow customers to mteract with the same organization when traveling across the country, which reduces their uncertainty, and improves the expectation of good service from patronizing a hotel. More generally, the transformation to professionally managed organizations from owner-operated organizations is itself important because it has happened or is threatening to happen in so many industries.

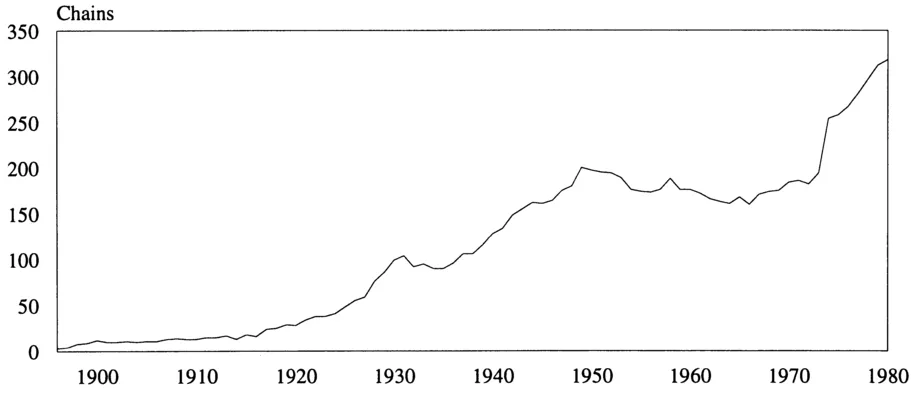

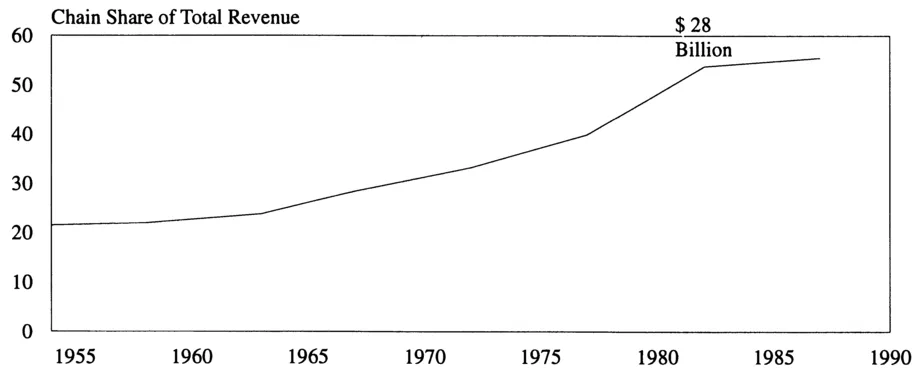

The transformation in organizational form is partly demonstrated by the growth in the number of hotel chains, shown in Figure 1-1. In 1896 there were three hotel chains in the United States, managing about thirteen hotels. By 1980 there were more than 300 chains managing more than 10,000 hotels. The hotel chain form has grown much faster than the industry. A small fraction of one percent of hotel rooms were part of chains in 1900, 15% were by 1930, and by 1980 more than 50% of hotel rooms were managed by chains. Associated with the growth in chains and rooms managed by chains is consistent growth in the share of hospitality industry revenue earned by chains, shown in Figure 1-2. In 1987 hotel chains accounted for $28 billion of revenue.

Figure 1-1. Number of Hotel Chains.

Figure 1-2. Percentage of Total Hotel Revenue Earned by Chains.

Source: U.S. Census of Business

The transformation to hotel chains also provides an opportunity to examine ideas about why one form of organization rather than another is used in an industry. Most of organizational theory in the last twenty years has been about the determinants of success for organizational forms. The influential arguments on this problem conclude that the environment organizations face, which consists of other organizations, technology, customers, laws and social norms, determines which form of organization will be successful. My position in this book builds on the idea that environments are fundamental determinants of organizational form, but differs from recent organizational theory by explicitly considering the role of entrepreneurs and organizations in influencing the environment. Some elements of the environment, for example government regulation, can be influenced by organizations and other interested actors. Consistent with the implications of this argument, I examine not only the influence of the environment on hotel chains, but the role of hotel-chain entrepreneurs and others m affecting the elements of the environment that matter for hotel chains. The elements of the environment that I focus on are the institutions that define the form of training in the hospitality industry, and the technology that allows owners of hotels to control their employees.

The rest of this chapter is dedicated to outlining the dominant theoretical explanations for the rise of organizational forms. I will concentrate on three streams of organizational theory: transaction cost economics, institutional theory and organizational ecology. The purpose of reviewing these theories is to generate an understanding of the possible influences on the rise of hotel chains as provided by research in other contexts, and to provide background for the theoretical contribution of this book. The chapters that follow develop the explanation of the rise of hotel chains. The second half of this book supports the arguments in the first half with detailed statistical analyses of the evolution of hotel chains in the United States.

TRANSACTION COST ECONOMICS AND EFFICIENCY ARGUMENTS

Transaction cost economics explains the prevalence of organizational forms with efficiency arguments. The short explanation for the existence of large professionally managed organizations is "because they are more efficient in some circumstances." The seeds of this approach were planted by Coase (1937) where the idea of using the transaction as the unit of analysis is introduced. In this classic work, questions such as why do firms exist at all and how large should fiims be expected to be are addressed. Coase's answers are essentially the same as the ones that economists such as Oliver Williamson and Alfred Chandler offer fifty years later. Williamson and Chandler represent the core of the transaction cost position as it is currently expressed.

Williamson has made his arguments in a number of articles and books, most notably Markets and Hierarchies (1975). A key departure from neoclassical economics is the use of the transaction as the unit of analysis and the resulting focus on transaction costs. Williamson has a broad classification for transaction costs, which includes all costs not associated with production. The most basic question he addresses is which economic transactions should be governed by markets and which should be governed by hierarchies (organizations). The answer is that it depends on the nature of the transaction. The three critical dimensions of the transaction are: the degree of uncertainty involved in fully completing the transaction, the size of transaction-specific investments, and the frequency of recurrence of the transaction (Williamson 1979). Generally, the higher the uncertainty, idiosyncratic investment, and frequency of a transaction, the more appropriate it is to be governed within an organization.

Williamson recognizes that his approach can also be used to explain more subtle variations in organization than simply markets versus hierarchies. He summarizes his position on organizational design as:

consistent with the general thrust of the Markets and Hierarchies approach, organization design is addressed as a transaction cost issue, and economizing purposes are emphasized. The general argument is this: except when there are perversities associated with the funding process, or when strategically situated members of an organization are unable to participate in the prospective gains, unrealized efficiency opportunities always offer an incentive to reorganize. (Williamson and Ouchi 1981a, 355)

So, the form of organization in an industry can be expected to be the most efficient form in transaction cost and scale economy terms.

The problem Chandler examines in The Visible Hand (1977) is a special case of the efficiency argument, and directly relevant to this study. By considering the rise of managerial capitalism in industrial enterprises in the late nineteenth century, Chandler examines the industrial counterpart to the transition in service industries that is the subject of the empirical component of this book. He argues that new technology created large increases in the economies of scale available to manufacturers Therefore, producers found themselves in a position to supply much larger markets than they had previously. This presented a number of problems of coordination throughout the distribution chain which were solved by vertical integration, creating huge, professionally managed organizations that dominated their industries. The role of the manager changed to meet the opportunities presented by these changes.

Like Williamson, Chandler's justification for the prominence of an organizational form is its efficiency advantages. Chandler identifies the advantages of the vertically integrated, professionally managed organization as those of coordination (which Williamson and Ouchi [1981b] claim as a type of transaction cost). By embedding the general argument in a historical transformation, Chandler is successful at illustrating that the advantage of an organizational form depends on the circumstances: "the visible hand of the managers took over when unit costs were lowered through administrative coordination, and this situation occurred in manufacturing when the technology of production permitted the volume output of standardized products to national and international markets" (Chandler 1981).

Perhaps the most frequently offered cnticism of the efficiency argument concerns the variation that remains on the organizational landscape. Perrow (1981) wonders why, if there are such advantages to vertical integration, GM and Ford still contract out for so much of their material requirements, and Boeing does not own an Airline. Similarly, Hamilton and Biggart (1988) observe that Japan, South Korea and Taiwan each have internal transportation and communication systems analogous to the ones that Chandler related to the growth of managerial capitalism in the United States. However, economic organization in these countries varies, and is dissimilar from that found in the U.S.

Despite its popularity with sociologists, this criticism amounts to little more than a caricature of the efficiency perspective. It ignores the basic contingency nature of transaction cost explanations. The form of governance that is most efficient for a type of transaction depends on the case, and although certain factors such as transportation technology dictate efficiency in one circumstance, they may not in another. As Daems has noted (1983, 42), "the superiority of a particular institutional arrangement is not absolute but is dependent on the specific needs for information and compliance (Daem's emphasis)." So, Boeing does not vertically integrate because the nature of its transactions makes vertical integration less efficient. Japan, South Korea and Taiwan differ in economic organization because they differ on characteristics other than transportation and communication technologies.

The same features that allow the efficiency position to respond to the above challenge lead to a more substantial criticism. Granovetter (1985) has accused Williamson of relying on bad functional explanations. The problem efficiency theorists have is that they don't explain how efficient forms are created and come to dominate. Williamson hints that an implicit Darwinian process is at work when he makes statements such as "over time those integration moves that have better rationality properties (in transaction cost and scale-economy terms) tend to have better survival properties" (Williamson and Ouchi 1981b, 389). However, the mere implication of a Darwinian selection process is not a sufficient response to the charge of bad functional ism. To support the expectation that efficient organizational forms will dominate it is necessary that (1) powerful selection pressures toward efficiency be operating and (2) there is some source of variation that creates the efficient organizational forms in the first place. There are challenges to both of these conditions. Despite this, "the operation of alleged selection pressures is [to Williamson] neither an object of study nor even a falsifiable proposition but rather an article of faith" (Granovetter 1985, 503).

It might be expected that Chandler's focus on historical dynamics would allow him to avoid the trap of bad functionalism, but it does not. This is particularly obvious in his explanation of the development of management. In that explanation, managers appear to change effortlessly to meet the needs of modem business enterprises. Large integrated firms require specialized skills so managers become increasingly technical and professional (Chandler's 1977 proposition 5). Brief recognition is made of the creation of business schools, professional associations and journals for managers, but nothing is said about the motives of the actors responsible. The impression given is that these things simply came into being as part of a society-wide recognition of the efficiency advantages of the professionally managed enterprise.

The criticism of efficiency arguments as bad fiinctionalism suggests that their failing is in fact the opposite of what Hamilton and Biggart (1988, S67) suggest when they accuse Williamson and Chandler of concentrating their whole causal argument on proximate factors. It is not that efficiency theorists "argue that the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand caused World War I" but rather that they offer a plausible underlying cause for observed forms of organization (efficiency) but fail to explain how those forms came to exist and dominate. And without an explanation of the creation and growth of efficient forms, the argument that things are the way they are because of efficiency rings hollow.

INSTITUTIONAL THEORY

A problem with reviewing institutional explanations for the development of organizational forms is that there are a number of institutional theories (Scott 1987a). Beyond the distinct versions, the theory has recently had a "creeping" quality, expanding in response to challenges to the point that now there are probably no organizational or economic phenomena that are not claimed by someone to be institutional. So, in order to consider institutional explanations for the development of organizational forms it is necessary to be strict. I will break institutional theory into what I feel are its two main expressions, the first treating institutions as rationalized, taken-for-granted elements of society and the second treating institutions as systems of social rules that define networks of social organization and exchange. I will refer to these versions as the preconscious and the conscious positions, reflecting their claims about the mechanisms by which institutions constrain actors. The preconscious position is best represented by Meyer and Rowan's (1977) classic article. They argue that institutional rules (defined as "classifications built into society as reciprocated typifications or interpretations," p.341):

have effects on organizational structures and their implementation in actual technical work which are very different from the effects generated by the networks of social behavior and relationships which compose and surround a given organization. (341)

In other words, institutions matter for themselves, and are not simply another dimension of exchange relationships. Actors comply with institutional rules to get legitimacy. Often legitimacy is accompanied by more material rewards such as positive evaluation by actors who supply the organization with resources, but these rewards do not explain institutional compliance. Organizations may adopt institutionalized myths to increase legitimacy "independent of the immediate efficacy of the acquired practices and procedures" (Meyer and Rowan 1977, 340). In fact, institutional forces may have such a strong taken-for-granted character as to be invisible to the actors they influence (DiMaggio 1988). As Oliver (1991,148) notes, "institutional theory illustrates how the exercise of strategic choice may be pre-empted when organizations are unconscious of, blind to, or otherwise take for granted the institutional processes to which they adhere. Moreover, when external norms or practices obtain the status of a social fact, organizations may engage in activities that are not so much calculative and self-interested as obvious or proper."

Efforts of the preconscious position to explain organizational forms focus on diffusion processes. The basic argument begins with an organizational form being adopted, perhaps for efficiency reasons, by some organizations. As more organizations adopt the form (Tolbert and Zucker 1983) and as powerful institutional actors champion the form (Strang 1987) its legitimacy increases which encourages further diffusion. Tolbert and Zucker (1983) applied this argument to explain civil service reform. Their empirical findings were that early adoptions of civil service reform could be predicted by city characteristics that made reform rational, while later adoptions could not. Tolbert (1985) found that colleges had administrative structures reflective of their control. Public colleges had officers to administer relations to the public sector independent of actual funding from the public sector, while private colleges had officers to administer relations to the private sector independent of actual funding from the private sector. Strang (1987) argued that central actors prefer to interact with large bureaucracies and found that school district consolidation increased as a function of state funding.

These empirical studies all illustrate a problem the preconscious position has with explaining the rise of professionally managed organizations like hotel chains. None of these three studies, and very few studies in this tradition (Haveman 1993 a and Hamilton and Biggart 1988) explain the organizational forms of for-profit enterprises. In fact, the theory itself claims that environments differ in the relative importance of their institutional and technical features (Meyer and Rowan 1977), and institutional influences are more important to organizations in the public sphere (Meyer and Scott 1983).

Another common feature in empirical work supporting the preconscious position is a "black-box" characteristic. Legitimacy, the factor that explains conformity to institutional pressures, is never operationalized. Instead, what is demonstrated is a relationship between the rise of an institution and the rise of an organizational form, or the difficulty of using rationality arguments to explain the rise of an organizational form. This indirect strategy of support invites alternative explanations. A particularly compelling alternative concerns the economics of information. Herd theory (for instance, Scharfstein and Stein 1990) suggests that when managers have imperfect information (which is almost ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Original Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Preface

- 1 The Rise of Organizational Forms

- 2 The Creation and Change of Environments

- 3 Advantages of Hotel Chains

- 4 Institutional Change: The Supply of Professional Managers

- 5 Technological Change: The Development of Internal Control

- 6 Methodological Overview and Data

- 7 Mortality of Hotel Chains

- 8 Foundings of Hotel Chains

- 9 Growth and Decline of Hotel Chains

- 10 Comparison to Independent Hotels

- 11 Discussion and Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- Index