- 292 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About This Book

Reflecting the breadth and diversity of dance in the Asia–Pacific region, this volume provides an in-depth and comprehensive study of Taiwan's dance history. Taiwan is home to several indigenous tribes with unique rituals and folk dance traditions, with an array of eclectic influences including martial arts and Peking Opera from China, and dance forms such as contemporary, neo-classical, post-modern, jazz, ballroom, and hip-hop from the West. Dance in Taiwan, led by pioneers such as choreographers Liu Feng-shueh and Lin Hwai-min, continues to have a strong presence in both performance and educational arenas. In 1973, Lin Hwai-min created Cloud Gate Dance Theatre, the country's internationally acclaimed modern dance company, and simultaneously produced a generation of dancers not only trained in modern dance and ballet, but also in Chinese aesthetics and history, tai-chi and meditation.

Including the voices of dance professionals, scholars and critics, this collection of articles highlights the emerging trends and challenges faced by dance in Taiwan. It examines the history, creative development, education, training, and above all, the hybrid practices that give Taiwanese dance a unique identity, making it central to the renaissance of Asian contemporary dance. In describing how the intersections of dance cultures are marked by exchanges, research and pedagogy, it shows the way choreographers, performers, associated artists and companies of the region choose to imaginatively invent, blend, fuse, select and morph the multiple influences, revitalising and preserving cultural heritage while oscillating between tradition and change.

Frequently asked questions

Information

1

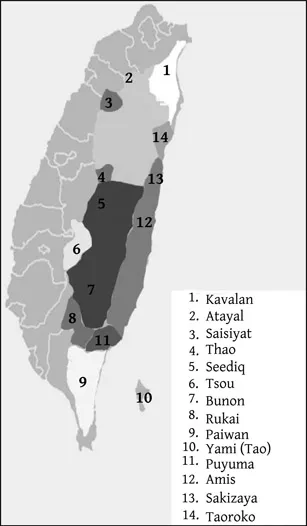

‘Holding Hands to Dance’: Movement as Cultural Metaphor in the Dances of Indigenous People in Taiwan*

From ‘Savage’ to ‘Indigenous’

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Identity, Hybridity, Diversity: A Brief View of Dance in Taiwan

- 1. ‘Holding Hands to Dance’: Movement as Cultural Metaphor in the Dances of Indigenous People in Taiwan

- 2. A Study of Banquet Music and Dance at the Táng Court (618–907 ce)

- 3. Colonial Modernity and Female Dancing Bodies in Early Taiwanese Modern Dance

- 4. Looking into Labanotation in Taiwan

- 5. Dance Education in Taiwan

- 6. Taiwan’s Female Choreographers: A Generation in Transition

- 7. Bridging the Gap through Dance: Taiwan and Indonesia

- 8. The Spectacular Dance: 2009 World Games in Taiwan

- 9. Roots and Routes of Cloud Gate Dance Theatre’s Nine Songs (1993)

- 10. An Introduction to Dance Technology

- 11. ReOrienting Taiwan’s Modern Dance: The New Generation of Taiwanese Choreographers

- Artist Voices and Biographies

- Index