![]()

1

Introduction

In 1924, the Geneva Declaration on the Rights of the Child enunciated a set of principles aimed at ensuring the well-being and protection of the child.1 It provided a moral benchmark for the evaluation of the special position of the child. Exactly 90 years later, in 2014, the Third Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of Child 2 set out an international complaint procedure for child rights violation. The Third Protocol allows children from states that have ratified it to bring complaints directly to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child if they cannot find a solution at the national level. According to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, the ability of children, in their individual capacity, to complain about the violation of their rights in an international arena has brought real meaning to the rights contained in the human rights treaties.

When children’s rights are being incrementally expanded in the international and domestic arenas, one wonders how a child can be exploited as a soldier, used as a human bomb or abused as a victim of human trafficking. Despite the advances in international law, technology, and human rights consciousness, we are witnessing the dreadful abuse of children in armed conflicts globally. These abuses are directly related to the denigration of the respect for international humanitarian and human rights law by parties to conflicts. There have been most disturbing reports of sexual exploitation and abuse of children by United Nations peacekeepers and civilians and non-United Nations international forces.

The 2016 Annual Report of the United Nations Special Representative for the Secretary General on Children and Armed Conflict listed nine state armed forces and nearly fifty non-state armed groups (NSAGs) that currently recruit and use children in fifteen countries around the world.3 The question arises: Who is a child soldier? In layman’s language, child soldiers are children under 18 years of age, who are used for military purposes. Some child soldiers are used for fighting – they’re forced to take part in armed conflicts, to kill, and commit other acts of violence. Some are forced to act as suicide bombers. Some join ‘voluntarily’, driven by poverty, a sense of duty, or the force of circumstance. Some children are used as cooks, porters, messengers, informants, spies or anything their commanders want them to do. Child soldiers are sometimes sexually abused. Whilst some may be in their late teens, others are as young as four years old.

Child Soldiers in History

Child soldiers are not a recent phenomenon. On the contrary, it was formerly commonplace for children to be enrolled in field regiments in Europe, although society was then substantially different. During the Age of Sail, children were assigned to man naval cannons, carry gun powder to the cannons and clean the cannons. These children were the so-called “Powder Monkeys.” In France, under Napoleon’s regime, “drummer boys” under Napoleon’s personal direction helped the army to play the drums in the communication systems on the battlefield. By the end of the eighteenth century, in certain regions of France, up to a third of children were killed or abandoned, in particular in towns and in times of famine or hardship. Many abandoned children joined regiments, and the youngest child in large families was often entrusted to the army. These so-called “lost children”, often served in the front ranks and in the most exposed positions. In this way, they “paid their debt” to society.

The American Civil War (1861-1865) could be considered the epitome of underage children at war. Although no concrete figures exist, according to conservative estimates, more than 200,000 soldiers of the Civil War, i.e., 10 to 20 per cent of the fighting force were sixteen and under. One of the youngest was Avery Brown, aged 8 years, 11 months, and 13 days. Brown lied about his age to join the service, claiming he was a full twelve years old. Although young soldiers performed the traditional role of drummers and later buglers, many underage volunteers engaged in combat and served with distinction during the war.4

All armies in the First World War used child soldiers. In the beginning of the war, the enthusiasm to join the battle was so great that young boys and even girls could hardly be stopped from enlisting. The officers responsible for recruitment closed their eyes when eager children clearly under the required age (18 years) showed up to join their armies. Hardly trained in military skills, the kids were sent to the trenches in Belgium, France, Russia and Turkey, where they mingled with the older soldiers and died with them. As many as 250,000 boys under the age of 18 served in the British Army during the First World War. Technically the boys had to be 19 to fight, but the law did not prevent 14-year-olds and upwards from joining in droves. They responded to the Army’s desperate need for troops and recruiting sergeants were often less than scrupulous.

Describing the training of a boy soldier in the First World War, Wilfred Owen wrote in ‘Arms and the Boy’:

Let the boy try along this bayonet-blade

How cold steel is, and keen with hunger of blood;

Blue with all malice, like a madman’s flash;

And thinly drawn with famishing for flesh.

Lend him to stroke these blind, blunt bullet-heads

Which long to muzzle in the hearts of lads.

Or give him cartridges of fine zinc teeth,

Sharp with the sharpness of grief and death.

When the Second World War started in 1939, very few countries were prepared for a protracted conflict. The drafting age was thus lowered repeatedly to ensure a steady supply of soldiers to the armies. Both Germany and the Allied countries resorted to the mobilization of their population for the war effort and almost every country recruited children below 18 years in their armed forces. In the years immediately preceding the Second World War, the US Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard allowed enlistment at age seventeen with parental consent, and at age eighteen without. Many lied about their age and concocted stories about their birthdates and their true identities. 5

The Cold War saw an almost systematic resort to conscription – massive or selective. However, child soldiers in this period were essentially an issue in the wars of decolonization. The use of child soldiers increased with the increasing number of internal armed conflicts in the 1990s. Children are vulnerable to both forced and voluntary recruitment by non-state armed groups. The breakdown of the protection mechanisms during conflicts makes it easier for such groups to access children, who in some cases, join armed groups as a survival strategy.6 Children are also among the first to be affected by internal conflicts. In South Asia, a large number of children have been killed and maimed during the conflicts in Nepal7 and Sri Lanka.

Children and terrorism have long intermixed in the modern era and in 2013 alone, the United Nations documented 4,000 cases of child recruitment, with thousands more likely undocumented. Although the number of states deploying children in their national armies has declined, children are deeply entrenched in armed conflict in the Middle East and Africa. At present, at least 1 in every 10 soldiers in armed conflicts is a child. These children not only carry weapons, but are also deployed in other ways such as porters, cooks, spies, guards or sex slaves.

Defining “Child” and “Child Soldier”

There are numerous challenges in defining the term ‘child soldier’. One of these is that the term may apply to a wide range of people with varying experiences and roles. For example in Uganda, some children were taken mainly for sexual purposes, while others served mainly as porters. In Syria, the ISIS 8 has allegedly recruited children and trained them as suicide bombers.

The definition of a child soldier can be deduced only indirectly from international conventions, treaties and national legislation. Although there are differences in the age threshold for taking part in hostilities and being recruited by the armed forces, all international instruments generally consider the age limit to be 18, some explicitly while others as an advisory. According to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, a child is “every human being below the age of 18 years unless under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier”.9

The definition of child soldier used by the UNICEF is based on the Cape Town Principles (1997), which state: A child soldier “is any person under 18 years of age who is part of any kind of regular or irregular armed forces in any capacity, including but not limited to cooks, porters, messengers, and those accompanying such groups, other than purely as family members. Girls recruited for sexual purposes and forced marriage is included in this definition.”

Child soldiers are also often referred to by child protection agencies as “children associated with armed groups and forces”. The Paris Principles (2007) state, “A child associated with an armed force or armed group” refers to “any person below 18 years of age who is or who has been recruited or used by an armed force or armed group in any capacity, including but not limited to children, boys and girls, used as fighters, cooks, porters, messengers, spies or for sexual purposes. It does not only refer to a child who is taking or has taken a direct part in hostilities.”10 The Paris Principles have changed the phrase “child soldier” to “a child associated with an armed force or armed group”, but the essence of the definition is the same.

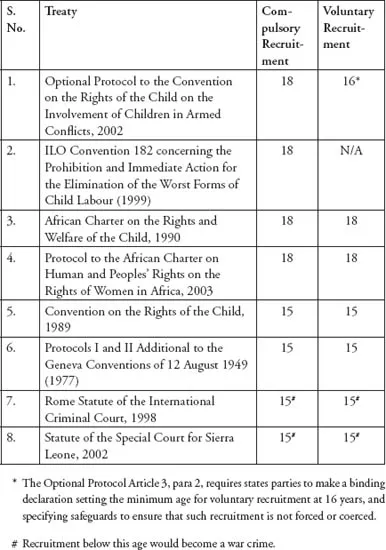

The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) recognized the conscription of children as detrimental to the rights contained in the convention. In Article 39 it stated that the state parties shall take all appropriate measures to promote the physical and psychological recovery of a child victim of….armed conflict. Although the CRC highlighted the prevention of child conscription as important, the earliest appropriate age of recruitment mentioned in the CRC at that time was 15 years.11 In a gross contradiction, the definition of a child in the same document was an individual under the age of 18.12 The document remained unchanged until 2000, when the UN adopted the Optional Protocol to the CRC on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict, now ratified by 166 member nations. The Protocol raised the age of compulsory recruitment to 18 for the State armed forces and non-state armed groups (NSAGs).13

The Optional Protocol requires states parties to make a binding declaration upon ratification, setting the minimum age for voluntary recruitment in the armed forces at 16 years or above.14 The Protocol lays down four safeguards related to the voluntary recruitment of those aged at least 16 into government armed forces and who will not in any circumstances be deployed in combat. These safeguards require that (i) the recruitment is genuinely voluntary; (ii) the recruitment is carried out with the informed consent of the potential recruit’s parents or legal guardians; (iii) the potential recruit is fully informed of the duties involved in such military service; and (iv) provides reliable proof of age prior to acceptance.15 In practice, most of the states that have become parties to the Optional Protocol have specified a minimum age of 18 or more. The age norms for recruitment in the armed forces under various treaties are shown in the following table. majority is attained earlier.”

Age Norms for Child Soldiers

Why Children Are Preferred as Soldiers

Armed groups see a number of benefits in recruiting children rather than adults. For example, in Mozambique, NSAGs preferred to recruit children because they were thought to have more stamina, be better at surviving in the bush, did not complain and followed orders more readily. Other reasons for the recruitment of child soldiers may be that children (i) work for lower pay; (ii) can be easily manipulated, intimidated and brainwashed; (iii) normally constitute no threat to leaders; (iv) may pose a moral challenge to enemy forces attacking them; (v) can be easily pressured into illicit activities such as trafficking or be exploited as sex slaves; and (vi) can replenish ranks and/or ensure long-term survival of the cadre.16 Children can also take extreme risks in battle, which makes them valuable fighters, especially when they are under the influence of drugs.

The proliferation of small arms, such as AK-47, handguns, light machine guns, and revolvers has contributed significantly to the use of child soldiers. The widespread availability of these weapons is an important factor that enables children to participate as combatants in armed conflict. Small arms are light-weight, cheap and easy to use.17 There could be other peculiar reasons for the recruitment of children by armed groups. For instance, Hamas used children to build tunnels because of their nimble bodies. In Colombia, child soldiers are known as “little carts” because of their ability to sneak hidden weapons through military checkpoints without arousing suspicion.18

Some factors which make children more vulnerable to recruitment by an armed group are: (i) Impoverishment; (ii) Travelling unaccompanied; (iii) Orphan-hood; (iv) Homelessness; (v) Living in an IDP or refugee camp; (vi) Being female; (vii) Illiteracy or lack of basic education; (viii) Relationship or friendship with someone who has joined an armed group; (ix) Relationship or friendship with someone who has been maimed or killed in conflict (x) Engaging in forced labour (e.g. in a mine, factory, crop field, etc.); (xi) Birth into an armed group; (xii) Belonging to a community that hosts a “community protection militia”; (xiii) Belonging to an ethnic or religious minority; (xiv) Being in conflict with the law; (xv) Addiction to drugs and/or alcohol.19

Mode of Child Recruitment

‘Recruitment’ is a general term covering any means, whether voluntary, forced or compulsory, by which a person becomes p...