Although we often think of infectious agents as the cause of disease, in fact many of the ailments we see in farm livestock are nothing to do with infection. Lameness is a good example, where simple trauma to the foot plays a major role in the aetiology of hoof problems. Poisoning, or, at the other extreme, trace element deficiency, can also lead to major health problems. The major factors leading to poor health in farm livestock may be listed as follows:

Infectious agents

A wide range of infectious agents can cause disease. Some exist as normal organisms on the animal or in its environment and only cause disease when in an unusual site or when the immunity of the animal is compromised (i.e. reduced). A good example of this is the bacterium Escherichia coli, most commonly known as E. coli. It is present in the intestine of all cattle, where it usually causes no problems. However, if it gains access to the udder it can cause quite severe disease, especially in the early lactation animal, whose udder defences against infection are poor.

For other infections, for example foot-and-mouth virus, disease occurs whenever the infection is present.

Infectious agents may be subdivided into the following categories:

- Bacteria

- Viruses

- Mycoplasma, ureaplasma, rickettsia and chlamydia

- Protozoa

- Fungi, yeasts and moulds

- Worms

- Ectoparasites (mange, lice, etc.)

Bacteria

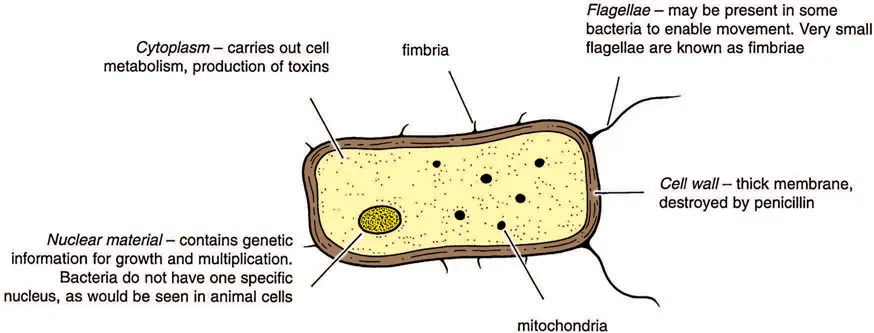

These are single-celled organisms which contain all the components needed for a separate existence. A typical bacterium is shown in Figure 1.1. It is a single cell, and consists of a thick outer polysaccharide structure, the cell wall, inside of which there is a protein membrane enclosing the cytoplasm and the nuclear material. The nuclear material contains the genetic components, the DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid), which is arranged as a double-stranded helix. Each strand consists of a sequence of the four nucleic acids, adenine, cytidine, guanine and thymine, A, C, G and T. It is the sequence of these nucleic acids that determines our genetic structure. For example A-C-T-G would be a different gene to C-T-G-A. DNA ‘instructs’ cell function by transcription of a second material, RNA (ribonucleic acid, sometimes referred to as mRNA, messenger RNA), which in turn determines which proteins and enzymes the cell produces.

DNA therefore functions as the regulator for all cell processes, determining the size and shape of the cell and the activities that take place within its cytoplasm. These ‘activities’ are the processes of reproduction and growth. The whole bacterium may be enclosed by a gelatinous capsule, a thick membrane which renders the bacterium more resistant to phagocytosis (i.e. being engulfed by white blood cells). Bacteria are therefore individual discrete units of life.

Figure 1.1 A typical bacterial cell. Even the largest bacteria (e.g. anthrax) are only 0.005 mm long. They multiply by dividing into two, and under favourable conditions this may occur every 30 minutes, so that one bacterium could produce 17 million offspring in 12 hours!

Given ideal conditions of warmth, nutrients and moisture most of them can also multiply outside the animal’s body. For example E. coli is said to double in numbers every 20 minutes. Under adverse conditions some bacteria produce a very resistant spore form, which can survive for many years. The classic example is that of anthrax, whose spores can persist in the soil for up to 40 years. Bacteria absorb nutrients for their growth from their immediate surroundings (e.g. blood, milk or body tissue) and excrete waste products, especially when they die. It is often these waste products that cause disease. The ‘waste’ is known as a toxin and the animal is said to be suffering from a toxaemia. Typical examples of toxaemia are acute E. coli mastitis and severe uterine infections.

Bacteria are the major cause of mastitis and foot infections, they are commonly involved in respiratory disease and they comprise the clostridial group of diseases such as blackleg, tetanus and anthrax. Bacteria commonly form pus and are also responsible for conditions such as navel ill, calf diphtheria and abscesses. Bacteria are killed by antibiotics, with different antibiotics being needed to kill the different species of bacteria. This is explained in more detail in the treatment section.

Viruses

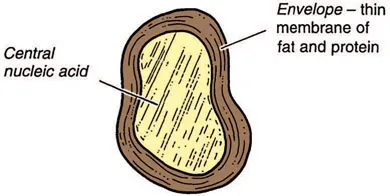

Viruses are much smaller than bacteria and may even infect and cause disease in bacteria. They cannot be seen with a normal light microscope; electron microscopy is required. They consist simply of central nuclear material, which may be DNA or RNA (ribonucleic acid), and this is surrounded by a capsule of fat and protein (Figure 1.2).

Because viruses have no cytoplasm or proper nucleus, they cannot carry out their own metabolic functions of growth and reproduction and they are therefore unable to multiply outside the animal’s living cells. For their survival away from the animal, and hence their transfer from one animal to another, viruses must be protected, for example in sputum (pneumonia viruses), milk (foot-and-mouth virus) or blood (EBL virus).

Once within the animal, viruses inject their own RNA or DNA into the animal cell and then use the metabolic processes within the cytoplasm of that cell for their own purposes of multiplication and growth. When a cell is packed full of viruses, it bursts and virus particles are released to penetrate and infect adjacent animal cells. It is the bursting of these cells that generally causes the detrimental effects on the animal and hence the signs of disease, although some viruses (e.g. those causing teat warts or EBL) induce a proliferation or excessive multiplication of animal cells to produce a tumour.

Figure 1.2 A virus particle. A virus is very much smaller than a bacterium. It uses the processes of metabolism within the animal cell for its own multiplication and growth, and as such it cannot live a separate existence away from the animal. This is very different from bacteria.

Both bacteria and viruses may be very specific in the site they choose to infect. For example, certain groups will grow only in the respiratory tract – and these cause the clinical signs of a cold, influenza or pneumonia. Others can live only in the intestine and they will cause scouring. It is by this mechanism that we associate particular strains of bacteria or viruses with specific diseases. Different strains of bacteria and viruses vary considerably in shape and size, in the same way that the different species of animal or bird are so variable.

Viruses cause a wide range of disorders including foot-and-mouth and diseases of the teat skin, and they are often the primary cause of calf pneumonia. Whereas antibiotics will kill bacteria, there is no specific drug to kill viruses. This is one reason why many virus diseases are controlled by vaccination. Mycoplasma, ureaplasmas and rickettsia are organisms that have some characteristics of bacteria and some of viruses.

Mycoplasma, ureaplasma, rickettsia and chlamydia

Mycoplasmas (and related ureaplasmas) are similar to bacteria except they have no cell wall. As such they are resistant to those antibiotics (especially the penicillins) that act by damaging the cell wall. Mycoplasmas can cause pneumonia and occasionally mastitis, joint, ear and brain infections.

Chlamydia and related rickettsia have nucleic acid and no cell wall. They cause enzootic abortion in sheep, psittacosis and Q fever.

Protozoa

Protozoa are also single-celled organisms, although they are larger and more complex than bacteria and may have a free-living existence. Examples include Babesia and Trypanosoma, which live in the blood of cattle and cause redwater, and coccidia and Cryptosporidia, both of which live in the intestine and cause scouring. Other protozoal diseases of cattle include Neospora, a cause of abortion, Theileria, which causes East Coast fever in southern Africa, and Besnoitia, which causes skin disease and abortion.

The treatment of protozoal infections requires specific therapy. For example, there is one drug specifically used against Babesia (imidocarb) and others against coccidiosis (e.g. toltrazuril; amprolium) and Cryptosporidia (halofuginone).

Fungi, yeasts and moulds

Fungi are very simple members of the plant kingdom. They are commonly found in the environment and primarily cause disease when they enter an unusual site, e.g. the udder, where they can cause a chronic mastitis. They do not respond to antibiotics and they need special therapy, e.g. natamycin (see Chapter 7) for therapy. There are some specific fungal diseases of cattle, e.g. ringworm, and another group of diseases where a common environmental fungus invades an unusual site. A good example of this is abortion caused by the fungus Aspergillus. Aspergillus may be seen as a b...