![]()

PART ONE

Introducing Christian Ethics

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

What Is Ethics?

FEW PEOPLE WISH to be seen as judgmental, or as imposing their sense of morality onto someone else. And in many modern countries it is considered more than bad manners to suggest that morality should be based on religious beliefs. Those who do base morality on religious beliefs may be seen as intolerant.

Nevertheless, humans are naturally moral creatures. That is to say, we do right and wrong, or good and evil, and we know that we do. We perform moral acts because we were raised in communities that taught us what morality is, and some of these communities are specifically religious. We have developed habits, good and bad. We act in certain ways because we have accepted someone or something as a moral standard for our actions. We do things we believe will produce good for ourselves and others. So to be human is to be moral. In fact, as far as we can see, we may be the only moral creatures in the cosmos! That is quite a responsibility.

“Who gives you the right to judge . . .?”

“Live and let live.”

“You can’t legislate morality.”

“Whatever. . . .”

Is the study of ethics simply a nonstarter?

Do you believe that it’s possible to make moral judgments at all?

A Definition of Ethics

You have probably used the terms ethical, moral, and immoral on many occasions. For example: “He is the most immoral person I have ever met,” or “She holds herself to a pretty high standard of ethics.” But what do these terms address? The answer is that they have to do with issues of right and wrong, virtue and vice, and good and evil. We are asking moral questions when we say, What is the right thing to do here? Who is responsible? Is good or bad going to result from it? Am I acting with integrity if I do this?

Notice that these questions are not about subjects like beauty, or strength, or profit. For instance, you may judge that your light blue shirt goes better with your jeans than your brown shirt. But while it might be true that the blue shirt is a better match than the brown, that truth is not a moral truth or a moral judgment. It is a truth and judgment about style and/or beauty. In the same category are questions such as whether one truck is better for the job than another, or whether one cleanser is more effective on your carpet than another. These are evaluative questions, but they evaluate mechanical, aesthetic, and chemical values, not moral ones.

What, then, is ethics? Am I making a grammatical error by using a singular verb (“is”) with a plural subject (“ethics”)? No, the term ethics is not plural. It is derived from the Greek term ethos, which means “character.” At its linguistic root, then, ethics is the evaluation of character.

Terms

Mores: shared manners, habits, and customs

Ethos: the character of a person or group

Norm: whatever serves as a model or pattern, a type or a standard

Morality and ethics are very similar; in fact, in common usage the terms are often interchanged. Morals are the actual manners, habits, and customs of humans that relate to right and wrong, good and evil. Ethics is more accurately understood as a systematic evaluation of the goodness or evil, the rightness or wrongness of human behavior. As a botanist studies plant life and a psychologist studies the human psyche, so an ethicist studies moral life. All normal adults are moral beings, because we all have norms and habits for behaviors that can be evaluated in terms of good or evil, right or wrong. Those who reflect on these motivations, actions, and outcomes are studying ethics.

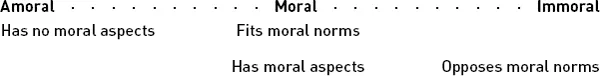

Is ethics, then, a description of human actions? No. Sociologists and anthropologists are in the business of describing and explaining social mores, but their work typically does not attempt to evaluate the rightness or wrongness of them. The study of ethics evaluates actions, motives, and consequences according to standards of right and wrong. Ethics does not just describe or explain — it judges. Ethics also does not address many human actions that are amoral. For example, tossing a pencil up in the air and then catching it is not a moral action. You did indeed perform an action, but it had no moral quality to it. Your action did obey some laws — the law of gravity and other physical laws — but it had nothing to do with morality. If an action is a moral action, it must have qualities like good and bad or right and wrong to it.

Let me give you another example. Say that my teenage daughter has promised me that she will be home by 11:30 P.M. on nights when she goes out. However, on one particular night, there’s a storm that blows a tree branch down onto the road she usually takes home. So she’s delayed until 12:30 A.M. because she has to take a wide detour. If this is the case, her coming home late isn’t wrong. It’s the result of a natural incident. Cars don’t leap over large trees, and she isn’t responsible for the storm, so her late return is an amoral event. On the other hand, if she decides that she’s having so much fun with her friends that she wants to stay until the party ends around 1:00 A.M., she is acting immorally. In this case, there is no natural obstruction blocking her return; she is responsible for the decision that causes her to be late and thus break her promise. What she does in the second instance is immoral. She has performed an action that is not in accord with the established moral standard that she and I agreed on. She has acted against the mores of our household, one of which is to keep your promises.

There are some things that are immoral no matter whose house you’re in. These moral norms apply quite widely. Determining what these are and why they are relevant is one important aspect of ethics. For example, I can think of no circumstances in which it would be right to kill a thriving child: to do so would be immoral, no matter where it occurred or who did it.

Here’s a summary for now: ethics is a systematic evaluation of moral issues, and a moral issue must include a person who is accountable. The term moral has two counterparts: amoral and immoral. Amoral describes an action that has no moral quality to it; immoral means that an action has a moral quality to it — that is, the quality of being opposed to a moral standard.

Are human actions, then, the only things that ethics studies? No, ethics also studies the motives, virtues, and vices that generate the actions — or the inaction. For example, perhaps you have the virtue of patience. This gives you the capacity to react to events in a deliberate and careful way. If, however, you have the vice of being hot-tempered or rash, you might react too quickly and harm yourself or others. The ethos of a person refers to her character, and character is an important aspect of ethics.

Ethics is not only about decisions; it is also about our moral formation over time. We can shrink or grow in virtue. We can become more or less law-abiding. We can generate more or less good. Therefore, ethics is both a snapshot of the morality of particular decisions on given occasions and a lifelong movie of the kind of moral persons we are becoming.

Christian Faith and Ethics

Earlier in the church’s history, ethics was not a distinct field of study, though it was always present. In fact, being a Christian disciple automatically raised ethical questions. Christians have always asked, How shall we follow Christ? What does it mean to be disciplined in Christian virtue? What is the right or the good that God would have me do? These are both old and new ethical questions, and they have both old and new answers. The fact that they are new is due to the differences of our culture and our individual context. Yet they are old because both Old Testament and New Testament believers have asked and answered similar questions.

The Bible uses many metaphors and similes that encourage us to develop a Christian morality. It tells us to “put on Christ,” “follow Christ,” “be transformed into the likeness of Christ,” “love one another,” and so on. Narrative passages in Scripture often call us to share in the life of God’s people, both ancient and modern. The Bible calls us to lives of holiness and justice and love and virtue. This book is a systematic study of these subjects. It is my hope that you, by interacting with this text, will become more clear about and conscious of your moral life.

This is specifically a study of Christian ethics. If I refer to “red ball,” you quickly have a picture of the object I’m talking about: it is more than likely round and probably bounces, and it has the characteristic of redness. When I say “Christian ethics,” I’m using the name of a religion as an adjective for a field of study. Biology and history are also fields of study, so when I say “Christian ethics” I am saying something about the kind of ethics that I am about to do, such as micro-biology or ancient history. The adjective “Christian” will direct this study of ethics at every point. I will look at the whole subject of ethics from the point of view of a Christian. I will be wearing “Christian glasses,” you might say.

Morality and Salvation

Since there is a difference between morality and salvation, this book will not address the process, for example, of becoming filled with the Holy Spirit; nor is it about the Rule of Saint Benedict. This book also does not assume that Christians don’t need to study ethics since they are saved. True, Christians are by nature perfected. Unfortunately, it is not true that being a Christian means that you are exceptionally moral; nor does it mean, inversely, that being a non-Christian assumes that you are immoral. This is because morality and salvation are two different things. Being a Christian is an absolute category. It addresses one’s standing before God: either you are reborn in Christ or you are not. Morality, however, is a different category. Morality focuses on human actions and virtues that can be evaluated in terms of right and wrong or good and evil apart from one’s standing before God. All humans do things that are right and wrong, or good and evil, regardless of whether they are Christian.

For example, let us imagine that one person steals an ice-cream cone from a child; let’s imagine that another person actually steals the child. It may be that the person who steals the ice-cream cone is a non-Christian and that the person who kidnaps the child is a Christian. All of the following could yet be true: both the Christian and the non-Christian did wrong; the Christian did something that was far more evil than what the non-Christian did; and yet the Christian will inherit eternal life, but the non-Christian will not.

Martin Luther used the phrase “at the same time justified and a sinner” to describe Christians. This dilemma is the source of our moral problem: we are both good and evil, we do right and wrong, and we are virtuous and vicious. It means that, as Christians, we can do moral evil, and a non-Christian can do moral good. It does not mean that someone is a Christian because he does good, or not a Christian because he does evil. The fact that Christians do evil has long puzzled theologians, as Luther’s statement shows. The fact that we are simultaneously saved and sinners is due to the distinction between the categories of salvation and morality. Being able to do moral good does not require Christian faith, and doing evil does not presum...