This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Crime Justice Society in Colonial Sri Lanka

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book explores the aspects of the history of crime in Sri Lanka during British colonial rule. It attempts to place crime within its economic, political, social, and cultural settings to contribute to an understanding of modern South Asia.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Crime Justice Society in Colonial Sri Lanka by John D Rogers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia de la India y el sur de Asia. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

POLITICS, ECONOMY AND SOCIETY

The aim of this chapter is to provide the background information necessary to understand the arguments of this book. The first section treats the colonial administrative and political structures. It is followed by accounts covering the main economic and social developments of the British period.

Administration and Politics

European penetration of Sri Lanka began in the sixteenth century, when the Portuguese established control over some coastal areas.1 Their rule was rarely peaceful, for they competed for power with Sinhalese and Tamil states. The Dutch replaced the Portuguese in the seventeenth century and established a relatively stable colony in the coastal regions of the island. The main concern of their administration was to profit from the monopoly over cinnamon, the principal export commodity. Only the Kandyan Kingdom maintained its independence in the interior. After 1739 it was ruled by members of the southern Indian Nayakkar dynasty, who adopted the roles of Sinhalese kings. The British ousted the Dutch in 1796, and two decades later, in 1815, assumed control over the entire island. The Kandyan Kingdom fell quietly to the British as a result of its internal weaknesses and divisions, but part of the aristocracy led a major rebellion in 1817–18. After it was crushed, the British took direct administrative control over the Kandyan districts.

In the early years of British rule the avowed principle of government policy was the continuation of policies of the previous regimes, the Dutch in the coastal areas or Low Country, and the Kandyans in the interior.2 In practice there were innovations, partially because of the perceived need to reduce the influence of headmen, and partially because British officials naturally governed on the basis of their own training and inclinations. In 1829 a Royal Commission of Enquiry, appointed because of recurrent annual deficits, began an investigation of the colony’s affairs. Four years later a wide-ranging set of reforms, named after the two commissioners, William Colebrooke and Charles Hay Cameron, was implemented.3 Many of the institutions and practices established at this time remained intact until the twentieth century.

The island’s administration was unified under a government structure shaped like a pyramid. At its apex was the Governor. He made policy with the aid of an Executive Council which was composed entirely of senior officials. He also presided over a Legislative Council which included a non-official minority. Governors generally appointed one representative for each of three Sri Lankan ethnic groups, the Sinhalese, Tamils and Burghers (Eurasians). The other three non-official positions were filled by local British residents. After the Legislative Council was expanded in 1889 a Ceylon Moor and an extra Sinhalese representative were also included.

All legislation had to be approved by the Legislative Council, but the Governor could control this body by ordering the official majority to vote in a certain way. Normally such action was unnecessary. In the 1860s there was open conflict between the Governor and the non-official members over the size of the colony’s military contribution to the imperial budget and other financial matters, but this fracas was the exception rather than the rule.4 The proceedings of the Legislative Council were sent to London for the perusal of the Colonial Office and were reported in detail by the local press. Legislation had to be confirmed by the Colonial Office, which took note of any opposition. Governors generally tried to get as much support as possible from the Legislative Council, and they usually succeeded.

Although the legislative branch was clearly subservient to the executive, the Supreme Court exercised power independently. Initially vacancies were filled from Britain, but by the late nineteenth century at least one of the three judges was Sri Lankan. Judicial officials at lower levels were normally members of the civil service. They were subject to transfer, but the executive branch was unable to interfere with specific decisions. Appeals were heard by the Supreme Court.

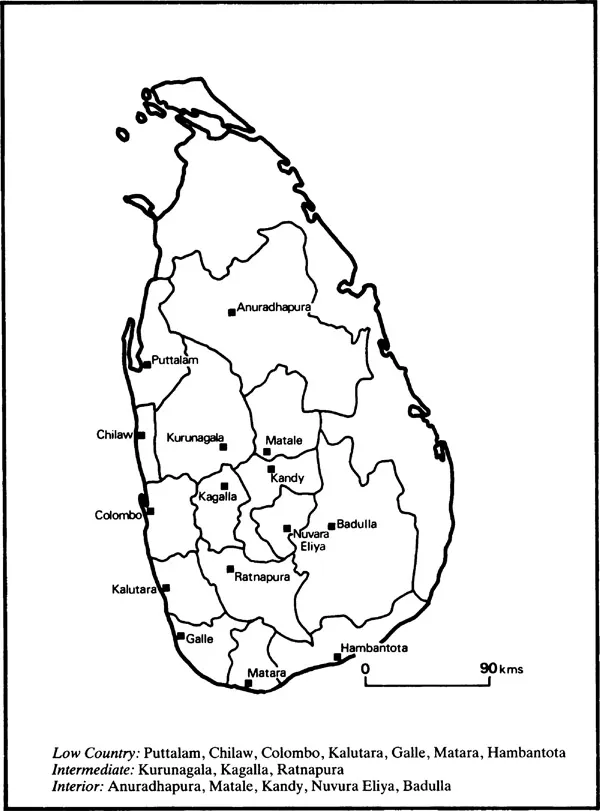

The Governor administered the colony through the highest ranking civil servant, the Colonial Secretary. All heads of department carried on a voluminous correspondence with this official. Outside of Colombo, the capital, the main representatives of colonial power were the government agents and assistant government agents. These officials were responsible for the collection of revenue and the general administration of the districts where they were stationed. Each worked from a permanent district headquarters called the kachcheri (Map 1.1.).

Map 1.1 Kachcheris, Districts and Regions, Sinhala Sri Lanka, 1900.

In the years immediately following the Colebrooke-Cameron Reforms civil servants were ill-paid and allowed to participate actively in outside economic ventures. Many owned coffee plantations, and not unnaturally were more concerned with the success of their investments than with carrying out government policy.5 In 1845 salaries were raised, provision was made for pensions, and restrictions were placed on economic activities. As a result, civil servants gradually developed a stronger bureaucratic ethos. This trend was strengthened in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries by the establishment of more stringent educational requirements and by the expansion of technical and specialist administrative departments.

Revenue officials ruled their districts through several levels of headmen. The lowest officials on the administrative tier were the village headmen, who were normally men of substance. The chief headmen, who were called mudaliyars in the Low Country and ratemahatmayas in Kandyan districts were persons of high status and much wealth. They exercised territorial jurisdiction over areas often inhabited by tens of thousands of people. The extent to which British administrators depended on them for information varied greatly according to the social composition of the district and the competence of the civil servant in charge. Another important Sri Lankan official was the kachcheri mudaliyar, who was in charge of the kachcheri staff and who often acted as an interpreter. These officials should not be confused with the many honorary and titular mudaliyars created by the British. Unless otherwise specified the term mudaliyar refers to officials with territorial jurisdiction.

In most districts only a few high-ranking headmen were paid a salary. Many lower-level headmen received a legitimate income by retaining a proportion of the fees paid to them for issuing various licences and for other duties. The reliance of the government on untrained and largely unsupervised headmen undermined government policies which were formulated as if headmen would act as local bureaucrats.

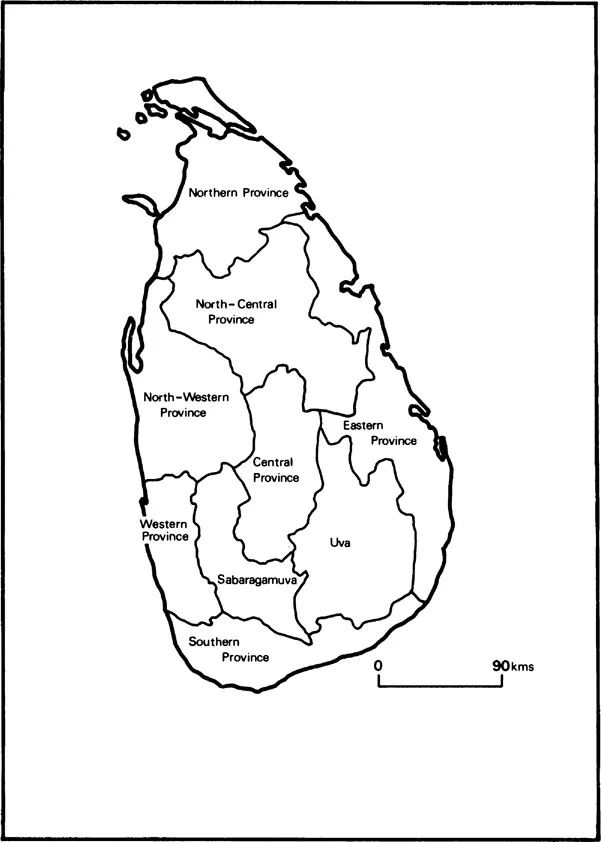

The provincial boundaries established by the Colebrooke-Cameron Reforms were deliberately designed to cut across traditional political and ethnic lines. This policy was motivated by a utilitarian-inspired belief that the island should be administered in a unified way. In the second half of the nineteenth century government policy shifted, partially as a result of agrarian unrest in parts of the interior in 1848. Many officials believed that these disturbances were prompted by needless interference with traditional society. It was felt that the more conservative backward-looking elements no longer represented a serious threat to British authority, but could on the contrary be placated and transformed into loyal allies. The ‘native aristocracy’ of Kandyan districts were all members of the Goyigama caste, and most were members of the Radala subcaste which had been influential in the Kandyan Kingdom. The authority of these headmen was increasingly supported by officials, and three new Kandyan provinces were created (Map 1.2). In the Low Country the link between social status and government appointments was less rigid, but nevertheless important. A group of predominantly Protestant families known as ‘first-class Goyigamas’ dominated the ranks of the mudaliyars.6 Some governors saw the ‘native aristocracy’ as a counterweight to upwardly-mobile Low Country families, many of them non-Goyigama, who had taken advantage of the commercial and educational opportunities of British rule.

Map 1.2 Provinces, Sri Lanka, 1900. Uva was formed from the Central Province in 1886 and Sabaragamuva from the Western Province in 1889.

In the second half of the nineteenth century urban local government provided the small but growing English-educated elite with a limited opportunity to exercise political power. Municipal councils were first established in Colombo and two other towns, Galle and Kandy. Local boards, with less power than municipalities, held sway over smaller towns. Officials acted as chairmen of both these bodies, but some councillors were elected by Sri Lankans who met certain property requirements. In many rural areas village committees were established. The name was misleading, for the jurisdiction of each committee included many settlements. Though the president of each committee was appointed, councillors were elected by universal manhood suffrage. The proceedings of the village committees, unlike those of all other official bodies, were in Sinhala, not English.

Government revenue was much less dependent on the surplus from subsistence agriculture than in neighbouring India. The grain tax usually amounted to about one-tenth the value of the rice crop, considerably less than the burden imposed on the Indian peasantry.7 In the nineteenth century it provided little more than ten per cent of government revenue. It was abolished in 1892, amidst justified concern that its harsh enforcement had contributed to rural destitution in some districts.8 Customs duties and related levies were more important, accounting for about one-third of government proceeds. The revenue from arrack and toddy provided a significant portion of official income, as did the salt monopoly, railway receipts and income from the commutation of an annual labour levy on adult men.

The administrative structures set up by the Colebrooke-Cameron Reforms, though subject to some change in the nineteenth century, remained largely intact until the early twentieth century. In 1912 official control over the Legislative Council was reduced when an election was held for an ‘Educated Ceylonese’ seat. More significant concessions were made in the 1920s, when a majority of the Legislative Council was elected by a franchise limited by ethnicity, education and wealth. This arrangement proved unsatisfactory because there was no corresponding transfer of executive power. The non-official majority was able to reduce the power of civil servants but powerless to fill the ensuing void.

Under the Donoughmore Constitution of 1931 the Legislative Council was transformed into the State Council, the members of which were elected by universal suffrage. Executive power in many fields was turned over to seven committees of the State Council. The chairmen of these committees made up a Board of Ministers. Although the Governor retained direct control over defence, finance and justice, Sri Lankan politicians wielded an increasing degree of executive power. The influence of government agents and chief headmen, on the wane since 1920, declined still further. In 1936 the post of District Revenue Officer was created to supersede the mudaliyars and ratemahatmayas. Full independence was granted in 1948.

The Economy

Sri Lanka bore many traits of a classical colonial economy. The island exported raw materials and imported food, textiles and other goods. Although this pattern was well established as early as the sixteenth century, the expansion of the market economy during British rule was unprecedented. More and more land was needed to grow crops for export and in some cases for the domestic market. The extent, timing and nature of this trend varied geographically, but by the early twentieth century virtually all districts were affected.

Coffee was introduced into the central highlands in the 1840s, and quickly became the most important cash crop. It was produced not only on large British-owned estates, but also in small gardens owned by the indigenous inhabitants, the Kandyan Sinhalese. The Sinhalese were however generally unwilling to work as labourers on large estates. Impoverished Tamil peasants from southern India were used instead. Since much of the work on coffee plantations was seasonal, most of these workers returned to India once the harvest was over. The ‘Indian Tamils’, as they came to be called, were of low status and had a reputation among British planters for being docile. The Sinhalese were thought lazy because of their reluctance to work for planters, but the poor living conditions of estate labourers are ample explanation of the failure to recruit Sinhalese workers.

Disaster, in the shape of a leaf disease, struck the coffee industry in the 1870s.9 By 1878 productivity had fallen and Sri Lanka’s economy faltered. The depression was not limited to the coffee-growing area; there was also a decline in employment in the packing industry in Colombo, and many temporary emigrants from maritime areas who had earned their livelihood providing services in the previously-expanding economy of the central highlands were forced to return home. Around 1883 the economic outlook began to improve. With great rapidity tea replaced coffee as the major plantation crop, and soon its acreage surpassed that of coffee at its height, for tea could be grown at more varied elevations than coffee. The change of crop was not without important social consequences. Unlike coffee, tea could not easily be grown profitably on smallholdings. Thus the Kandyan Sinhalese were denied a full share of the renewed prosperity. Moreover, because tea required a more stable labour supply than coffee the plantation Tamils became more settled, though many continued to retain some ties with India.

Tea and coffee were not the only important export crops. A coconut belt had grown up along the south-western coastal fringe during the late eighteenth century. Elsewhere, the tree had grown randomly at lower elevations, and the nut was used for local consumption. In the nineteenth century the amount of land devoted to coconut cultivation expanded sharply, especially...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Abbreviations

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1 Politics, Economy and Society

- 2 The Administration of Law and Order

- 3 Cattle Stealing

- 4 Homicide

- 5 Riots and Disturbances

- 6 The Social Context of Crime

- 7 Conclusions

- Appendices

- References

- Index