eBook - ePub

Mobile Homes

Spatial and Cultural Negotiation in Asian American Literature

This is a test

- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The writers discussed in the book include Chiang Yee, Hualing Nieh, David Wong Louie, Fae Myenne Ng, John Okada, and Toshio Mori. Their publication dates span from the 1940s up to 2000.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Mobile Homes by Su-Ching Huang in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & North American Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Mutual Authentication of "the Silent Traveller" and the American Landscape: Chiang Yee's American Travelogues

"Though I always prefer to travel or stroll silently, I do not mind placing myself in a melting pot so long as I do not get boiled." (Chiang, The Silent Traveller in Boston 131)

"[...] relics of the early Indians and the Dutch settlers are abundant in New York, and these are of great interest. But I wondered why Chinatown should be singled out for inspection. If it were for exotic flavour or foreign customs, then surely the Syrian, Spanish and Slav quarters should be equally popular." (Chiang, The Silent Traveller in New York 191)

Coming from an elite background, Chiang Yee (蔣彝) "the Silent Traveller" presents an exceptional case of Asian American mobility as theorized by Sau-ling Cynthia Wong. Unlike many of his contemporary Asians in America, most of whom were laborers and hence economically and geographically immobilized, Chiang as an artist/writer could afford frequent leisure travels. While his initial journey out of China was dictated by Necessity, his subsequent travels in Europe and America were for Extravagance. In addition, the way Chiang presented himself in public and his silence about his family and personal life reflect the gender division of travel/travail/labor. Granted Chiang may have been disadvantaged due to being an ethnic minority in the United States, yet he was privileged with regards to gender and socio-economic class. His travel writing well exemplifies the intricacies of race, class, gender, and nationality.

This chapter examines the American travelogues by Chiang in terms of their construction of class and ethnic identity. I propose that Chiang's evasiveness on political issues may have resulted from his elite class status as well as from his identity as a Chinese exile struggling for recognition in the West.

THE EDUCATION OF A CHINESE AMERICAN INTELLECTUAL

Illustration 1: Chiang, Yee. The Silent Traveller in Boston (New York: Norton, 1959) Courtesy of Chien-fei Chiang

Chiang gained recognition in both writing and painting shortly after he moved to the West. Born in Kiu-kiang, Kiang-si Province (承恩 in China in 1903, he had received traditional private education (mostly in Confucianism and Chinese classics) before being enrolled in a public high school.1 Chiang's father was a traditional Chinese intellectual and an accomplished painter and poet. Growing up under his father's tutelage, Chiang was also well versed in Chinese painting and literature. Seeing how China was torn asunder by the joint military forces of Western colonial powers, he believed that Western science and technology was what China needed most, and decided to get a Bachelor's degree in chemistry instead of art. He later worked as a chemistry teacher, as a journalist and finally as county chief in various counties along the Yangtze River. It was at his post as a county chief that Chiang witnessed firsthand the corruption of the Nationalist Government from within and also the afflictions on the Chinese people by Japanese imperialism from without. In the early 1930s, before China had barely recovered from civil wars, the Japanese launched their invasions; most people in rural areas were still living in poverty, and Chiang was hoping to implement some reforms to improve their living conditions. However, disagreements with his superiors and colleagues prevented Chiang from carrying out his ideal. In 1933 he felt he had to leave China, both out of frustration and to protect himself from being persecuted by his power-hungry superiors. He left his paralyzed wife and four children behind, a fact he never disclosed until in his final book, China Revisited: after Forty-two Years, published in 1977.

In Britain, Chiang got a position teaching Chinese at the University of London. A talented Chinese painter and calligrapher, he was asked to write books to introduce Chinese arts to Western audiences. Prior to embarking on his first journey to the United States in December 1945, Chiang had already published several books. Two of them, The Chinese Eye: an Interpretation of Chinese Painting (1935) and Chinese Calligraphy: an Introduction to Its Aesthetic and Technique (1938), went through several editions; he also published children's books illustrated by himself. In addition, while in Britain he developed "the silent traveller" series, initially travelogues of his trips to culturally significant locations of Britain, such as the Lake District, Oxford, London, Edinburgh, and so forth. ' After the Second World War Chiang turned more international and included the United States and other countries in this series. He stayed in New York City for six months as visiting lecturer at Columbia University and in 1950 published The Silent Traveller in New York.

In November 1952, at his publisher's suggestion, Chiang visited Boston and San Francisco consecutively and sojourned in each city for six months. In 1955 when Chiang got a teaching position at Columbia, he then settled down in New York permanently. He subsequently revisited Boston and San Francisco several times and produced The Silent Traveller in Boston, published in 1959, and The Silent Traveller in San Francisco, published in 1964.

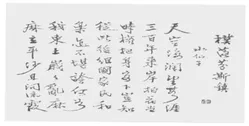

Chiang Yee wrote in the traditions of both Chinese and Western travel writing. On the one hand, his travelogues reiterate the Western ideal of the voyage as salvation, progress, freedom, expansion of knowledge, and so forth (Van Den Abbeele xv). On the other, his adoption of a pseudonym, the fusion of different genres (shi 江西省九江縣—poetry, wen 詩—essays, shu 文—Chinese calligraphy, hua 書—sketches and paintings), and his allusions to Chinese art, literature as well as history also conjure up the tradition of travel writing (youji 畫) by traditional Chinese literati (wenren 遊記). Chinese classical poems and paintings abound in his travelogues, such as the painting of Boston Public Garden (see Illustration 1, Boston 100) and numerous Chinese classical poems in calligraphy, among them "Provincetown" (see illustration 2, Boston 264).

Illustration 2: Provincetown, Chiang, Yee. The Silent Traveller in Boston, New York: Norton, 1959), Courtesy of Chien-fei Chiang

Esther Tzu-Chiu Liu in her doctoral dissertation on Chiang identifies the tradition of Chinese travel narratives by referring to Wu Cheng-en's (文人 吳) Journey to the West (Xi You Ji 劉鶚) from the Ming Dynasty, and Liu E's (劉鶚) Travels of Lao Ts'an (Lao Can You Ji 老殘遊記) from the Qing Dynasty (90). Both are works of fiction that vigorously satirize and criticize their contemporary societies. Chiang's travelogues, however, do not seem to fit in with that tradition. Although both Journey to the West and Travels of Lao Ts'an have travelogue (youji) overtones in their titles, they differ from Chiang's travelogues on at least two counts: first, they are fabricated narratives, whereas Chiang's are allegedly factual accounts; second, their demonstration of discontent with and criticism of society does not find easy counterparts in Chiang's travel books. Instead of dissatisfaction with the western society, Chiang's travelogues are mostly about his contentment with the host cities/countries as well as his appreciation of different natural and social landscapes. The sentiments expressed in the poems and paintings in his travel books call to mind the tradition of landscape travel writing (shanshui youji 山水遊記) by Chinese writers like Su Tung P'o (蘇東坡)and Tao Chien (陶潛), whom Chiang alludes to repeatedly in his travelogues. Although both Su and Tao were quite vocal in expressing their nonconformist political views, Chiang refers to their works not to evoke the critical tradition of Chinese literati but solely for their lyrical sensitivity, as Su and Tao were both excellent landscape/pastoral (shanshui 山水/tianyuan 田 園) poets. While Chiang's identification with both poets serves to uphold him as a successor to the Chinese heritage of landscape travel writing, his partiality toward their less political dimension suggests his own evasiveness on political issues.3

In his emulation of both Chinese and Western peripatetic traditions, Chiang establishes himself as a universalist and humanist traveler who combines literary features of both worlds. This chapter focuses on Chiang's American travel books, in which Chiang presents himself as both a traveler on the Grand Tour (in the Western tradition) in quest of "authentic" American experience and an "authentic" Chinese scholar contemplating American landscapes and cityscapes from a uniquely enlightened Chinese perspective.4

Chiang's authenticating strategies hinge on stressing his kinship to Chinese culture as well as revealing his erudition in Western art and literature. The combination of these traits seem to establish Chiang as an authentic Chinese intellectual; such an identity in turn validates his observation of the United States, marking whatever he describes in his travelogues as genuinely American. In addition to his allusions to Chinese and Western cultures, Chiang's authenticating strategies comprise his identification of his white American associates and Chinese intellectual friends. In this way, his authentication is closely linked to his socio-economic class status. Coming from an elite background and with sufficient means, Chiang could better negotiate the American surroundings and therefore occupied a drastically different position from that of earlier Asian migrants, who were forced on the road out of economic necessity or racially motivated hostilities.

However, to uphold his position as a universalist traveler, Chiang had also to skirt certain political issues in order not to offend his targeted white readers. In his travelogues, he seldom touches upon racism or other unfavorable aspects of the United States. Even when he refers to the Chinese laborers working on the Pacific Railroad or when he visited Angel Island, Chiang never brings up the discrimination against the Chinese by European Americans.

A CHINESE FLÂNEUR IN THE U.S. METROPOLIS

Chiang is like Charles Baudelaire's painter/flâneur, who is able to "be away from home and yet to feel [him]self everywhere at home" (Baudelaire 9). This description of Baudelaire's fits Chiang perfectly well both in terms of Chiang's peripatetic practice and of his philosophy. In his lifetime he produced thirteen travel books (including China Revisited), and in all of which he permitted himself enjoying landscapes worldwide. His travelogues show him at home everywhere. To feel comfortable everywhere, incidentally, is a Confucian adage: "A gentleman feels self-possessed everywhere" (‘‘君子無入而不自 得"). Starting his New York travelogue with one of Confucius's sayings, Chiang proves his affinity not only to Confucianism but also incidentally to flânerie. The flâneur is a gentleman of leisure; he observes, unperturbed, the restless throng; he is a man of the crowd and yet not in the crowd (Tester 3). Priscilla Parkhurst Ferguson puts it succinctly: "Flânerie requires the city and its crowds, yet the flâneur remains aloof from both" (27). According to Keith Tester, what sets the flâneur apart from the crowd is his knowledge of his own seeming mediocrity in the crowd.5 Because he looks like everyone else, he can go wherever he wants and observe everything without being noticed. In this sense, the flâneur is someone wearing a mask; he disguises himself as an ordinary pedestrian so that he may mingle in the crowd and, cloaked by anonymity, witness whatever happens in public places.

The association of Chiang with flânerie helps explain two important traits of Chiang's in his travel books: his superior class status and his identity as an artist. The flâneur is "a prince who everywhere rejoices in his incognito" (Baudelaire 9) and "the sovereign in control of a world of his own definition" (Tester 4). He attributes meanings to what he observes in the bustling streets and "distil[s] the eternal from the transitory" (Baudelaire 12). A writer/painter/poet, Chiang traveled across the American continent and captured the transitory—what Baudelaire also terms modernity—in his travelogues. In the beginning of his New York travelogue, Chiang talks about rapid changes in the "modern" world that leave him frequently confused, and writing seems to be the way to render the modern world intelligible and comprehensible to him. In his American travel books he confers meanings upon what he observes, and his interpretation of the U.S. society is certainly unique in the sense that he looks at it from a distinct class and ethnic perspective.

Traveling has long been considered a status marker. As Georges Van Den Abbeele suggests, a voyage to a distant place is supposed to help a person gain "cultural experiences" and increase one's "social value" in the home community (xvii, xxx). While Dean MacCannell asserts the equality of "all men" in sightseeing (146), there are indeed discrepancies in transportation, lodging, and other kinds of services according to the gender and socio-economic class of the traveler. A middle-class traveler like Chiang did enjoy exclusive accommodation and special arrangements when he visited places. For instance, when Chiang called on museums, usually the curators arranged to show him special collections and accompany him on his visits. Wherever he went, he was entertained by local celebrities, such as Van Wyck Brooks and Pearl Buck, among others, who took him to exclusive clubs, the Tavern Club in Boston, for example (Boston 53-4). Clubs are not simply

Illustration 3: Erwin D. Canham at The Christian Science Monitor, Chiang, Yee. The Silent Traveller in Boston (New York: Norton, 1959), Courtesy of Chien-fei Chiang

Illustration 4: The Sculptors at the Grand Central Art Gallery, Chiang, Yee. The Silent Traveller in New York (New York: The John Day Co., 1950), Courtesy of Chien-fei Chiang

Illustration 5: Van Wyck Brooks and his Family, Chiang, Yee. The Silent Traveller in Boston (New York: Norton, 1959), Courtesy of Chien-fei Chiang

places where people relax and get meals; rather, their exclusive clientele and personalized services—the "intangible products" in John Urry's term (69)— make them another status marker. Several drawings in Chiang's travelogues feature himself and his friends in high places, such as the editor of the Christian Science Monitor, Erwin D. Canham (see Illustration 3, Boston 55), the sculptors at the Grand Central Art Gallery (see Illustration 4, New York 161), or Van Wyck Brooks and his family (see Illustrat...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction The Politics of Mobility: Asian Migration, American Expansion, Transnationalism

- Chapter One Mutual Authentication of "the Silent Traveller" and the American Landscape: Chiang Yee's American Travelogues

- Chapter Two Female Nomadology: Re-reading Ethnic Schizophrenia in Hualing Nieh's Mulberry and Peach

- Chapter Three "We Just Cooked Chinese Food!": Gastronomic Mobility and Model Minority Discourse in David Wong Louie's Novel The Barbarians Are Coming

- Chapter Four Transnationality, Heterogeneity, and Spatial Negotiation in Asian American Fiction

- Notes

- Works Cited

- Index