This is a test

- 318 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Matters of the Mind

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book presents a popular and authoritative account of the dramatically different ways in which philosophers have thought about the mind over the last hundred years. It explores the effect of the major turning points in recent western philosophy as well as the influence of the leading figures.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Matters of the Mind by William Lyons in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

The Twilight of the (Two Worlds’ View

The soul clapped hands

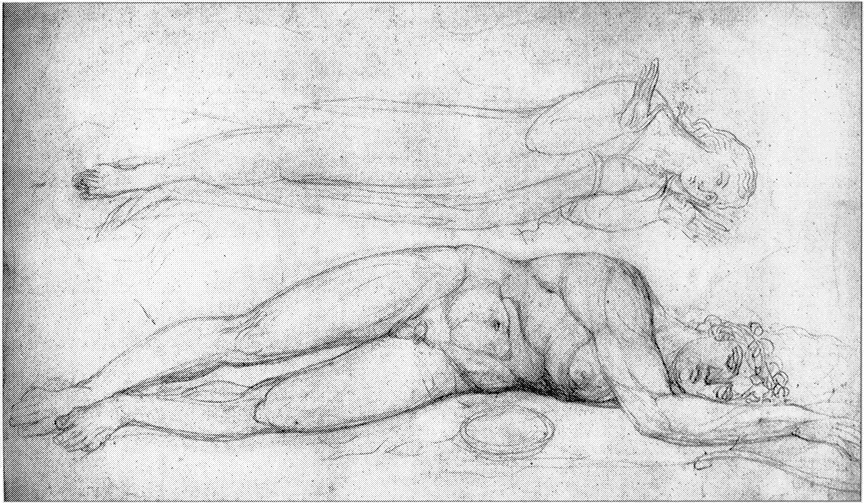

We are all familiar with the image of John Brown’s body mould’ring in the grave while his soul goes marching on, and many of us will have read in Charles Dickens’s The Old Curiosity Shop about poor little Nell’s body lying in solemn stillness upon her little bed while her soul, that little bird, first nimbly stirred and then took flight from its earthly cage. Many of us will also have attended a funeral in which the presiding minister, reading from the burial service in The Book of Common Prayer, will have declared that ‘forasmuch as it hath pleased Almighty God of his great mercy to take unto himself the soul of our dear brother here departed, we therefore commit his body to the grave’. It is part of western culture that we humans are made up of a soul or spirit which inhabits a body and that upon the death of the body the spirit will depart. Perhaps the most beautiful passage illustrating this traditional belief is contained in an anecdote about William Blake, as related by a contemporary to his nineteenth-century biographer, Alexander Gilchrist:

At the commencement of 1787, the artist’s [William Blake’s] peaceful happiness was gravely disturbed by the premature death, in his twenty-fifth year, of his beloved brother [Robert]: buried in Bunhill Fields the 11th February. Blake affectionately attended him in his illness, and during the last fortnight of it watched continuously day and night by his bedside, without sleep. When all claim had ceased with that brother’s last breath, his own exhaustion showed itself in an unbroken sleep of three days’ and nights’ duration. The mean room of sickness had been to the spiritual man, as to him most scenes were, a place of vision and of revelation; for Fleaven lay about him still, in manhood, as in Infancy it ‘lies about us’ all. At the last solemn moment, the visionary eyes beheld the released spirit ascend heavenward through the matter-of-fact ceiling, ‘clapping its hands for joy’ – a truly Blake-like detail. No wonder he could paint such scenes! With him they were work’y-day experiences.1

While they would not have claimed to have seen departing souls clapping their hands with joy at being at last freed from the confines of their earthly bodies, in the last decades of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth century, most philosophers and psychologists would have held a view that was not very different from Blake’s. They would have held an academically sanitised and suitably secularised version of this dualism of soul and body, though, by then, they would have referred to the dualism as that between mind and body. Many, perhaps most people, who are untainted by any acquaintance with contemporary philosophy or psychology, would still see things in this same dualistic way today.

Figure 1.1 A dualistic vision: William Blake’s The Soul Hovering over the Body Reluctantly Parting with Life.

The story told in the first half of this chapter is the story of how the fin-de-siecle, academic, secular versions of this dualism of mind and body had been given their basic shape by the work of Descartes. In the second half of the chapter, the story told is of how the Cartesian2 orthodoxy was called into question in a fundamental way in both philosophy and psychology in the early decades of the twentieth century. The bulk of the book, however, is the story of what, after much turbulent debate over the last sixty years, has been put in place of this Cartesian and commonsense orthodoxy. Now, however, it is time to begin the story by referring briefly to Descartes and to how he came to set the agenda for the modern debate about mind and body.

Figure 1.2 The father of modern dualism about mind and body, the French philosopher and scientist, Rene Descartes.

René Descartes (1596–1650) was an extraordinarily gifted seventeenth-century French mathematician, physiologist, physicist and philosopher. His initial interests were in mathematics. While still in his twenties he invented analytical geometry, whereby positions in space can be plotted by reference to three artificially-fixed lines or axes laid out at right angles to each other in three dimensions, and meeting at a point, the origin point. The link lines or ‘coordinates’ running from the position to be plotted to these axes are still known as Cartesian coordinates. A little later on, in his physiological phase, given the resources of his time, he hypothesised remarkably accurately about the physiological mechanisms involved in various organs and systems of the human body. In particular he made contributions to the physiology of the human eye and the human digestive system and to the study of limb reflexes in man and animal. He wrote an important work on meteorology (the study of weather) and, on account of that work, he is often credited with putting forward the first correct explanation of the nature of rainbows. In propounding his revolutionary ideas about scientific knowledge and scientific method, wittingly or unwittingly he laid the foundations for investigations in empirical psychology for the next three hundred years. Yet, with something approaching extreme perversity, Descartes is now best remembered through the fact that most twentieth-century accounts of mind define themselves in opposition to what they take to be Descartes’s account. In the history of ideas, Descartes is like the great soccer player who is only remembered nowadays as the player who missed a penalty shot in the 1998 World Cup.

To understand Descartes’s account of mind, it is necessary to understand something of his approach to scientific method, because, in effect, his account of the former arose as a by-product of his account of the latter. In regard to the latter, his account of scientific method, his aim was to provide a doubt-proof foundation and a secure method for that paradigm of the objective approach to knowledge that we now call science. In this context the phrase ‘objective approach’ calls upon two senses of the term ‘objective’. First, it refers to the gaining of information about the world via careful disinterested observation which can be replicated by other disinterested observers and which, at least in more modern eras, can be bolstered by experiments under laboratory conditions. In short, it refers to the scientific approach. Second, it refers to the fact that the object of such careful observation is (a world out there’ and so objective in relation to any subject observing it. Descartes believed that he could provide this doubt-proof foundation for science by setting himself the project of making sure that the very process of observation itself, which was at the core of his account of an objective scientific method, was immune to sceptical doubt about its data. Otherwise, how could we be sure that our senses are not deceiving us? If we can be gulled by optical illusions with comparative ease, such that we see a stick in water as bent or a heat haze in the desert as a lake, perhaps we should not rely on our senses for the authority of our scientia or ‘strict knowledge’ of the world or anything else.

Somewhat unexpectedly, Descartes did not set out upon this project by seeking a way of ensuring that the knowledge we gain of the world from our senses was immune to illusion. Rather, more boldly, he immediately proposed a firm foundation for all our knowledge, whether of the world or of anything else. He suggested that this firm foundation, indeed a rock solid one, could and should be erected upon the indubitable knowledge we had about the objects and events of our interior world, the world of each person’s own consciousness. In a sense he was saying that, previously, philosophy had got things back to front. Every other form of knowledge, including of the very existence of an external world, was at best a reliable inference, at least ultimately, from the indubitable knowledge of the contents of consciousness gained by this subjective route of self-consciousness.

Descartes believed that he could demonstrate that this was the correct approach to finding a foundation of exact and certain knowledge by engaging in a strategic ploy which later commentators called his ‘method of universal or radical doubt’. The ploy began with the attempt to see whether one could doubt everything, absolutely everything. If one found that in fact there was something one could not doubt, then this could become the firm foundation for the whole structure of human knowledge. As we shall see, however, Descartes encountered great difficulties in moving from his claim of having discovered an indubitable foundation to his reconstruction of even the ground floor of the skyscraper of human knowledge.

Descartes’s discovery of that ‘something’ which could not be doubted by anyone, and which was to be his firm foundation for all knowledge, is most clearly and dramatically announced in his Discours de la Methode (Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting Reason and Reaching the Truth in the Sciences) of 1637. Originally the Discourse was the introduction to a collection of essays on mathematical and scientific topics (the Optics, about the refraction of light through lenses, Meteorology and Geometry), which were to display the new mathematically based methods of scientific enquiry. In section IV of the Discourse, Descartes wrote:

But immediately upon this [adoption of the strategic ploy of doubting everything] I noticed that while I was trying to think everything false [to doubt the truth of everything], it must needs be that I, who was thinking this (qui le pensais), was something. And observing that this truth ‘I am thinking (je pense), therefore I exist’ was so solid and secure that the most extravagant suppositions of the sceptics could not overthrow it, I judged that I need not scruple to accept it as the first principle of philosophy [that is, the ‘indubitable foundation’] that I was seeking.3

In his reply to the Second Objections (objections made by various writers to another of his works, the Meditations),4 the argument, ‘I am thinking, therefore I exist’, was written in Latin as Cogito ergo sum and that version has subsequently assumed fame. Many philosophers have smeared much ink on a great deal of paper wondering whether the Cogito argument is valid or whether, for example, Descartes should have written ‘Some thinking (the doubting) is going on at this moment, therefore there exists, at least at this moment, a thought’ or ‘If the thinking is that I am thinking, then there is, at least at this very moment, a subject that thinks it thinks.’ The Cogito is also a staple of the stock pot for that thin gruel called ‘Lecturer’s Witticisms’. One spoonful should suffice to satisfy curiosity: ‘You can’t, of course, substitute “I am, therefore I think”, for the Cogito, for that would be to put Descartes before the horse.’ Be that as it may, Descartes himself believed that, with the Cogito, he had discovered the indubitable foundation for all knowledge and proceeded to build upon it.

Descartes pointed out that the indubitable facts of self-consciousness, such as that I am now thinking, for example, are clear and distinct and immediate presentations of consciousness. You do not have to observe them or argue for them; they just confront you in your own stream of consciousness. You cannot escape knowing about them. This, suggested Descartes, was a clue to the essence of consciousness, which in turn was the essence of mind. For Descartes, our mental life was one and the same thing as our interior subjective waking (or else dreaming) conscious life.

Somewhat curiously, at least from the perspective of our time, Descartes was less certain about the existence of the physical world. In our age, most people, if they think at all about such things, are dedicated above all to affirming the undeniable existence of the physical world which we observe with our senses, and about which the natural sciences provide us with such astonishing details. Given his initial strategy, Descartes now felt the need to invoke a connection or to build a bridge between our immediate and indubitable knowledge of objects and events in our stream of consciousness (his foundation for all knowledge) and our knowledge of the physical world as mediated by our senses. The connection or bridge that Decartes proposed, namely God, was something that would have little appeal to many in our more agnostic age. If, Descartes argued, we had clear and distinct ideas in our consciousness, and so a very strong conviction, to the effect that we are now perceiving our own bodies or perceiving some object or event in the physical world, then God must have allowed these ideas so to present themselves in such a vigorous way to our consciousness. If this exceedingly strong and most pervasive of convictions was illusory, then the very allowance of such a deceitful state of affairs at the heart of our mental life implied that God himself must be deceitful. This would imply that God was not perfect, which, in turn, would imply that there was, strictly, no God at all.

Descartes, of course, needed and duly produced a separate argument for the existence of God. However his argument for God’s existence does not seem to be any stronger than the foregoing invocation of God as a philosophical deus ex machina who ultimately puts the firmness into knowledge’s firm foundation. His best-known argument is considered to be unconvincing because it seems to depend upon introducing into our consciousness a ‘clear and distinct idea’, and so in consequence a conviction, that God must be a perfect being, and so must exist (for existence is a perfection), before there has been and can be an opportunity to introduce God as a guarantor that any such ‘clear and distinct ideas’, and subsequent convictions, are not illusory. God as guarantor can only come after God has been shown to exist but, embarrassingly, here God seems to be needed to show that He Himself exists. This point was made in Descartes’s own time by his contemporary Antoine Arnauld as part of his set of objections to the Meditations.

Descartes himself believed, however, that the upshot of this intricate series of arguments was the firm conclusion that we can be assured that we do have knowledge of the existence of an external material world and of our own bodies, and that the essence (or essential characteristics) of matter is to be extended and to be at rest or in motion.

I have spent some time explaining Descartes’s quite complex progress in arriving at what he believed was a firm and indubitable foundation for our scientific observations because it is also the source of what later critics of the Cartesian system have dub...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Chronology

- 1 The Twilight of the ‘Two Worlds’ View

- 2 Observing the Human Animal

- 3 Nothing but the Brain

- 4 Computers to the Rescue

- 5 The Bogey of Consciousness

- 6 The Pit and the Pendulum

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index