Introduction

According to current archaeological thinking, Sitio Conte was a regional meeting place for residents of Gran Coclé that accommodated various activities (Cooke et al. 2000:154; Isaza Aizpurúa 2007:80–85; Haller 2008:185, 191).1 During the period CE 750–950 (Cooke et al. 2003),2 the cemetery at Sitio Conte served at least two hundred Conteños,3 and Briggs (1989:73) calculated that adult men composed the majority of the deceased (72 percent). In a few tombs at Sitio Conte, the total number of body ornaments climbs into the thousands, which is separate from the ceramic vessels and other artifacts documented in a number of tombs. The amount of body ornaments directly associated with one specific person in a tomb varies widely from zero to dozens. The cemetery does indeed distinguish certain individuals as wealthy consumers of goods.

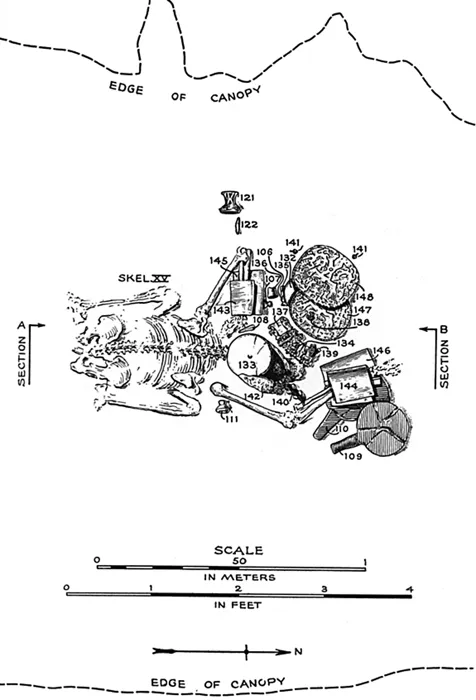

This chapter focuses on a man who the archaeologists directly associated with twenty-five items, the majority being body ornaments in gold alloy, stone, resin, and animal products. For reasons explained below, I call this man “Lord 15.” This study confirms one of the general observations made by Samuel Lothrop (1937:14), lead archaeologist of the Peabody Museum’s excavations and author of the two-volume site report: “Articles of personal adornment were worn in great quantity” at Sitio Conte.4

I rely on all available archaeological data to examine Lord 15’s body ornaments. Lothrop’s (1937, 1942) site report contains the excavation data and object illustrations, as well as the first round of interpretation, for the Sitio Conte objects excavated by the Peabody Museum. The report comprehensively lists the grave’s contents and illustrates Lord 15 and his ornaments in a ground plan (Figure 1.1). Aside from the report, I consulted the museum’s archives and object collections in person.5 Five items of Lord 15 transferred to the Brooklyn Museum were studied in photographs.6 Fortunately, my previous research about the ceramics at the cemetery also relied on these diverse data sources (O’Day 2003).

With these data, I refocus on the individual ornaments as the set they originally were: a group of pieces that contributed to a unified effect on Lord 15’s remains. Following excavation, the ornaments were separated from one another for accession into the museum collection. Likewise, the site report organized the description and analysis of the excavated material by function, media, and imagery rather than people’s sets. It is appropriate for the ornaments to be examined as a set since examples have been identified in other ancient American cultures. In addition to his ornament set, the archaeologists associated Lord 15 with a celt, shark tooth, ceramic incense burners, ceramic vessels, and multimedia mirrors. These items with the ornament set make up his mortuary ensemble. The ornament set is the primary focus in this chapter, although the other objects are related to the ornament set.

To visualize Lord 15’s reunited ornament set, this chapter presents four computer-rendered illustrations. No comparable representation of a specific Sitio Conte person exists. The precedents are in Andean studies: recent projects based upon excavations indisputably more sophisticated than those carried out at the Sitio Conte in the early twentieth century. Furthermore, the archaeologists who performed the Andean excavations were able to participate directly in the creation of the illustrations. Despite such enormous differences in collecting and representing the data sets, it is possible to construct illustrations that are faithful to the Sitio Conte archaeological record and also improve the ability to see the ornament set of a specific man. Only one person’s ornament set is reconstructed here, so it is hoped that more projects will be initiated in the wake of this one.

With Lord 15’s ornament set reunited, I attempt to redirect the conversation away from the well-documented role of ornaments in displaying a person’s rank and wealth in Gran Coclé societies (Briggs 1989; Helms 1979) and toward the set’s role in reconstituting Lord 15. To do so, I rely on Chris Fowler’s (2004) assessment of personhood in diverse archaeological contexts (especially mortuary ones), Eduardo Viveiros de Castro’s (1998) discussion of Amerindian personhood, and Stone’s (2011) examination of Amerindian shamanic visionary experience in relation to ancient American art. Lord 15’s mortuary ensemble portrays an inclusive and enduring (after death) conception of personhood much like Fowler describes: humans, nonhuman animals, and objects are people. Examples of each of these categories have a role in Lord 15’s mortuary ensemble. The capitalized names of nonhuman animals and objects in this chapter signal their personhood. In addition, I draw more conclusions about the ornament set based upon Viveiros de Castro’s description of Amerindian ideas of how humans envision themselves and the other people in the universe, such as the nonhuman animals. Stone’s book provides many insights relevant to the imagery on specific ornaments, ranging from animal interactions and transformations in shamans’ trances to the creative ambiguity in artistic embodiments of shamans’ visionary experiences. In addition, Stone offers new ideas about well-known (but poorly interrogated) kinds of imagery, such as the so-called composite beings, double-headed creatures, independent human heads and eyes, and twisted patterns. In all, the archaeological database and variety of anthropological and art historical sources hopefully render an original contribution to Sitio Conte studies.

This also should be an important contribution to Isthmo-Colombian studies.7 Sitio Conte has occupied a central place in the scholarly conversation about this area, and its gold ornaments have exerted especially powerful influence since they constitute the largest collection of published archaeologically excavated (i.e., not looted) goldwork (Cooke et al. 2003:93; Quilter 2003:1). There is another way of looking at this situation (Quilter 2003:2): archaeologists have excavated goldwork at only a few other Gran Coclé sites (Cerro Juan Díaz and El Caño), so if one wishes to work with provenienced gold ornaments from this part of the Isthmo-Colombian area, then the Sitio Conte corpus has been one of few options. Despite the site’s perhaps disproportionate significance in Isthmo-Colombian studies and the overemphasis accorded its goldwork (Briggs 1993:158–60; Haller 2008:83), no Sitio Conte person has ever had his/her ornament set thoroughly investigated until now.