eBook - ePub

Concept-Based Curriculum and Instruction for the Thinking Classroom

- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Concept-Based Curriculum and Instruction for the Thinking Classroom

About this book

Think Beyond the Facts!

Knowing the facts is not enough. If we want students to develop intellectually, creatively problem-solve, and grapple with complexity, the key is in conceptual understanding. A Concept-Based curriculum recaptures students' innate curiosity about the world and provides the thrilling feeling of engaging one's mind.

This updated edition introduces the newest thought leadership in Concept-Based Curriculum and Instruction. Educators will learn how to

- Meet the demands of rigorous academic standards

- Use the Structure of Knowledge and Process when designing disciplinary units

- Engage students in inquiry through inductive teaching

- Identify conceptual lenses and craft quality generalizations

Explore deeper levels of learning and become a Master Concept-Based Teacher.

Carol Ann Tomlinson, William Clay Parrish, Jr. Professor

University of Virginia, Curry School of Education

"As factual and procedural knowledge are a click away, education needs to foster contextualization and higher order thinking through a focus on transferable conceptual understandings. This essential book translates the needed sophistication of concept-based learning into actionable classroom practices."

Charles Fadel, Author of "Four-Dimensional Education" and "21st Century Skills"

Founder, Center for Curriculum Redesign

Visiting Scholar, Harvard Graduate School of Education

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1 The Thinking Classroom

Classroom Snapshots

In an elementary school, the classroom buzzes with activity. Children work in small research and discussion groups, intent on discovering the answer to a question posed by the teacher: “How do simple machines increase force?” Students collaborate as they hypothesize and design and carry out experiments using levers, pulleys, and ramps. The teacher asks the students to use the concepts of force and energy to describe the results of their experiments. Students express ideas, question each other, and extend their thinking. New understandings emerge and are recorded in sentences next to drawings of their simple machines. A visual scan of the classroom confirms an active learning environment. Student work lines the walls, and books, art prints, science materials, mathematics manipulatives, and technology are evident in the plentiful workspace.

In a secondary school, students are skilled at evaluating the credibility of a range of primary and secondary sources on global pollution. They process the information through the conceptual lens of environmental sustainability as they think beyond the facts. They compare notes with students around the world using blogs and other social media to display and share their research and deepening understanding of global pollution and sustainability. These students produce a score of intellectual, artistic, and informative products.

Down the hall in another classroom, students sit in pairs. Their assignment is to define the key science terms listed on a vocabulary worksheet. The words are from a chapter in their science textbooks. Together the students first locate a vocabulary word in the text and then think about how the word is used in context and discuss what they believe is the meaning of each word. Once they have come to agreement, each child records the definition on his or her worksheet. The teacher moves among the students providing guidance and feedback as needed.

Did you notice a difference in the three classrooms? The first two lessons take place in Concept-Based classrooms. Students are engaged intellectually. The learning experiences promote inquiry and clearly move students toward conceptual understanding. The third snapshot is of concern. Yes, students are in small groups, on task, and following the teacher’s directions, but intellectual engagement is low. Although students will generate definitions, with the teacher’s guidance and their resources, there is no evidence that conceptual understanding is advanced.

The art and science of teaching go beyond the presentation and extraction of information. Artful teachers engage students emotionally, creatively, and intellectually to instill deep and passionate curiosity in learning. Teachers know how to use effectively the structures offered by the science of teaching to facilitate the personal construction of knowledge. The personal construction of knowledge cannot be assumed. The teachers are clear on what they want their students to know factually, understand conceptually, and be able to do in relation to skills and processes.

An unknowing observer may not realize that students engaged in different stages of inquiry within a classroom buzzing with activity are actually involved in goal-oriented learning. The teacher artfully designs a lesson with questions and learning experiences so that students are investigating, building, and sharing disciplinary knowledge and understanding aligned to academic standards. The learning is purposeful. But the teacher also designs lessons to encourage the realization of additional insights and understandings generated by the students. In the first two lessons, the student discourse, the teacher’s guiding questions, the evidence of inquiry learning, and the opportunities for students to make meaning and express ideas through various media represent a thinking classroom. Within that classroom, intellectual development, mindful learning, and creative expression are key instructional goals of Concept-Based Curriculum and Instruction (CBCI). Here is another example.

Mr. Chen is a high school world history teacher. His students have raised many questions about the 2015–2016 mass migrations of people from Syria and Iraq to European nations. Mr. Chen wants students to internalize two enduring lessons of history: “Warring factions within a nation can lead to mass migrations of people seeking safe and supportive living conditions” and “Receiving nations face complex problems related to aiding or assimilating refugees.” He developed the following learning experience to help students internalize facts supporting these understandings and arrive at the lesson of history.

Contest: Can We Solve World Problems?

Our class is participating in a national high school contest. The focus of this year’s contest is to uncover the reasons for and the complexities of mass migrations caused by war and conflict. As a class team, we need to respond to the social, political, and economic issues that caused the mass migrations of people from Syria and Iraq in 2015–2016 and to the consequences for the nations receiving the immigrants.

You are going to divide into two groups to tackle this issue. Group 1, using factual evidence, you need to complete the end of this sentence with a concept in order to create a generalization: “Warring factions within a nation can lead to mass migrations of people seeking…. ” I expect you are going to generate at least 8–10 concepts from the facts you research.

Group 2, using factual evidence, you need to complete the end of this sentence with a concept: “Nations receiving large numbers of refugees fleeing war need to solve the problem of…. ” Again, you must cite a concept to end your generalizations, and justify each concept with evidence from facts related to the mass migration of people from Syria and Iraq in 2015–2016.

Finally, each group will report its generalizations and findings to the class, and then collectively we will generate a possible solution to this complex world issue, which we will submit to the contest committee.

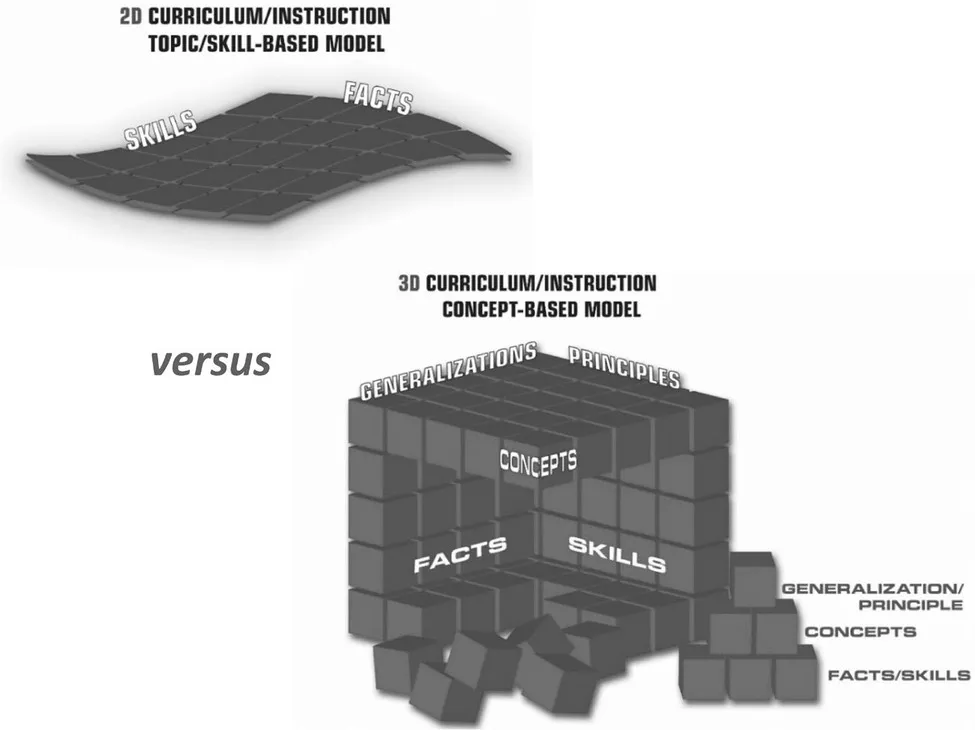

Thinking classrooms employ CBCI design models. These models are inherently more sophisticated than traditional models because they are as concerned with intellectual development as they are with gaining knowledge.

CBCI designs are three-dimensional—that is, curriculum and instruction are focused on what students, after a lesson, will be able to

- Know (factually),

- Understand (conceptually), and

- Do (skillfully).

Traditionally, curriculum and instruction have been more two-dimensional in design (focusing on students knowing and being able to do)—resting on a misguided assumption that knowing facts is evidence of deeper, conceptual understanding. Figure 1.1 compares the two-dimensional versus the three-dimensional curriculum and instructional models.

Figure 1.1: Two-Dimensional Versus Three-Dimensional Curriculum and Instructional Models

Let us consider performance indicators, which are typical expectations across history standards:

- Identify economic differences among different regions of the world.

- Compare changes in technology (past to present).

These performance indicators are written in the traditional format of content “objectives,” with a verb followed by the topic. It is assumed that the ability to carry out these objectives is evidence of understanding, but, as written, they fail to take students to the third dimension of conceptual understanding where the deeper lessons of history reside. Students research and memorize facts about the economic differences in regions, but the thinking stops there. Try this task to reach the third dimension.

Complete the sentences by extrapolating transferable understandings (timeless ideas supported by the factual content):

- Identify economic differences among different regions of the world in order to understand that…

- Compare changes in technology (past to present) in order to understand that…

What do you think the writers of these performance indicators for middle school expected students to understand at a level beyond the facts? Below are some possible endings:

- Identify economic differences among different regions of the world in order to understand that … geography and natural resources help shape the economic potential of a region.

- Compare changes in technology in order to understand that … advancing technologies change the social and economic patterns of a society.

We cannot just assume that traditional instruction will help students reach the conceptual level of understanding. In fact, years of work facilitating the writing of these conceptual understandings with teachers has shown us that teaching to the conceptual level is a skill that takes practice. Extrapolating deeper understandings from factual knowledge is not easy work. It involves thinking beyond the facts and skills to the significant and transferable understandings. It involves mentally manipulating language and syntax so that conceptual understandings are expressed with clarity, brevity, and power. When they begin this writing process, teachers across the board say, “This is hard work!” The learning curve is steep, but with a little practice, teachers take pride in their finely honed understandings.

Becoming a three-dimensional, Concept-Based teacher is a journey that merges best practices in teaching and learning with a developing understanding of brain-based pedagogy. But we have much to learn. So let’s get on with the journey.

The Brain at Work

The brain weighs about 3 pounds but is far from lightweight when we consider its amazing ability to power the human body. Without our brains, we could not think, move, feel, or communicate! Since the 1990s, the cognitive sciences have produced significant research on the anatomy and functioning of the brain and on the implications of neuroscience for teaching and learning (Eagleman, 2015; Sousa, 2011b, 2015; Sylwester, 2015; Wolfe, 2010).

In a commentary published in LEARNing Landscapes, David A. Sousa (2011a) tells us that researchers have now acquired so much information about how the brain learns that a new academic discip...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Acknowledgements

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Illustration List

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 The Thinking Classroom

- Chapter 2 The Structures of Knowledge and Process

- Chapter 3 Designing Concept-Based Instructional Units

- Chapter 4 Inquiry Learning in Concept-Based Lessons

- Chapter 5 The Developing Concept-Based Teacher and Self-Assessments

- Resource A: Concept-Based Curriculum Glossary of Terms

- Resource B Sample Verbs for Level 2 and 3 Generalizations

- Resource C Concept-Based Graphic Organizers

- Resource D–1 Concept-Based Curriculum: Unit Design Steps

- Resource D–2 Concept-Based Curriculum: Unit Templates

- Resource D–3 Concept-Based Curriculum: Unit Examples and Culminating Unit Assessments

- Resource D–3.1 Unit Example: Circle Geometry

- Culminating Unit Assessment: Circle Geometry

- Resource D–3.2 Unit Example: Are We Really Surrounded by Waves?

- Resource D-3.3: Unit Example: Building Language Through Play

- Resource D-3.4 Unit Example: English Language Arts

- Resource D-4.1 Concept-Based Lesson Planner Template

- Resource D-4.2 Concept-Based Lesson Plan Example

- Resource E Checklist for Evaluating Concept-Based Curriculum Units

- Resource F Mathematics Generalizations for Secondary Grade Levels

- Resource G Early American Colonization: History Unit Web

- Frequently Asked Questions

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Concept-Based Curriculum and Instruction for the Thinking Classroom by H. Lynn Erickson,Lois A. Lanning,Rachel French in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education Administration. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.