1

Introducing the anti-portrait

Fiona Johnstone and Kirstie Imber

This volume is dedicated to the anti-portrait, broadly conceived as a portrait that resists or disrupts the received art-historical conventions of its genre.1 Some anti-portraits retain a partial investment in figuration; others opt for a conceptual or object-based representation of their subject, evoking the sitter not through physiognomic likeness but through strategies that might include verbal or written inscription; the use of indexical or bodily traces, biodata or digital profiling; and many other forms of symbolic or metaphorical elicitation besides. Post-romantic notions of psychological or emotional depth may be interrogated; in many cases the anti-portrait is concerned with scrutinizing the operations of subjectivity, rather than expressing the particularized identity of a given individual. As a whole, however, this book is less concerned with arriving at an authoritative definition of the anti-portrait so much as considering the impact that these insubordinate artworks might have on an understanding of the genre as a whole.

While the term ‘post-genre’ is now commonplace in literary studies, it has rarely been considered in relation to the discipline of art history. Jacques Derrida has remarked that ‘as soon as the word “genre” is sounded … a limit is drawn. And when a limit is established, norms and interdictions are not far behind.’2 The concept of genre therefore implies a desire to raise borders, regulate boundaries and eliminate impurities; fighting against this, however, is a reciprocal law, one of ‘contamination’ that makes it impossible not to mix genres. The anti-portrait embodies the compulsion to cross borderlines and sully ‘pure’ genres, even while paradoxically reflecting on and regulating the margins of its own. Also writing in relation to literature, Carolyn Miller has suggested that genre should be dependent not on substance or form but on the action that a text (or, in this case, an artwork) is used to accomplish.3 Following Miller, the question that the chapters in this volume seek to address is not ‘What does a portrait look like?’ but rather, ‘What can a portrait do?’

This is a timely moment for a critical (re)-evaluation of the anti-portrait, with several recent exhibitions in the UK and the United States suggesting a new institutional willingness to consider instances of portraiture that break with the genre’s historical ties to figuration and question its persistent associations with physical or emotional likeness. In the summer of 2017, the National Portrait Gallery in London mounted an exhibition of works by Howard Hodgkin, a British painter known primarily for abstraction. Advancing a direct challenge to the orthodoxy of the physiognomic portrait, the vast majority of works displayed in Howard Hodgkin: Absent Friends were non-figurative (although almost all referred to known individuals). For example, Hodgkin’s Self-Portrait of the Artist (1984–7) is an abstract arrangement of vibrant green and magenta daubs on a stormy blue background, edged with rows of hazy yellow discs; nothing about the work implies a discernible human form. Controversially extolling Hodgkin as ‘one of the late twentieth-century’s greatest portraitists’, the curator Paul Moorhouse acknowledged that some observers ‘will inevitably not consider his paintings to be portraits at all’.4

In anticipation of the question: ‘In what way can this be considered a portrait?’ Moorhouse suggests that the concept of resemblance has come to unfairly dominate the way in which we read paintings; for many, he notes, ‘there is an abiding conviction that in order to refer to something other than itself, a painting has to replicate the appearance of its subject’.5 He situates this view historically in relation to the rise of abstraction in the early twentieth century and its accompanying belief that the abstract painting has no referent outside of the artwork and exists solely on its own pictorial terms, a doctrine that still carries authority today. This, Moorhouse argues, is a misunderstanding that fails to account for the ability of the human mind ‘to read one thing as embodying or expressing another’. Our capacity for metaphorical thinking, Moorhouse concludes, means that the abstract form is ‘uniquely eloquent’,6 possessing expressive or associative qualities that can powerfully evoke (rather than directly depict) an individual human presence.

Not everyone was convinced: the art critic for the Observer complained that Moorhouse ‘has had to perform some pretty high-level semantic gymnastics’ in order to justify the exhibition’s use of the word ‘portraiture’.7 While acknowledging that Hodgkin himself considered all these pictures to be portraits, the critic challenges the artist’s judgement in designating them as such. Picking on the work Absent Friends (2000–1), from which the exhibition takes its title, the critic objects: ‘To my eyes, this painting is not a portrait. Rather, it is an expression of what it means to miss someone.’8 This response to the exhibition implies a conception of portraiture based on what Hans Georg Gadamer has described as a work’s ‘occasionality’; that is, the intentional connection between the portrait image and the human original.9 The relationship established by Absent Friends is less between the image and its ostensible referent, as between the image and the emotional response that the sitters and their absence have induced in the artist. Put another way, Hodgkin’s sitters are here defined by their affective trace on the world rather than by their particularized individual identities, suggesting an understanding of personhood as fluid and unbounded, and generating radical new possibilities for the pictorial portrait.

What is a portrait (and does it have to look like someone)?

Most people instinctively think that they know what a portrait is: a likeness of a particular person, perhaps painted, photographed, sketched or sculpted, with various possible degrees of artistic skill or mimetic accuracy. This likeness might aim to express something about the sitter’s personality, emotional state or some other aspect of their ‘inner self’; alternatively, it might convey a sitter’s social identity by drawing attention to, for example, a profession or familial role. In either case, the portrait is tacitly understood to communicate something important about a person through their visual re-presentation. These assumptions are supported by the standard textbook definitions of portraiture. For Richard Brilliant, writing in Portraiture (1991), portraits are ‘art works, intentionally made of living or once living people by artists, in a variety of media, and for an audience’.10 Brilliant’s book barely broaches the topic of non-figurative portraits; he places significant emphasis on visual resemblance, noting that the term ‘likeness’ has become a synonym for a portrait. Similarly, in her introduction to Portraiture: Facing the Subject (1997), Joanna Woodall makes a claim for the centrality of naturalistic portraiture, and in particular the portrayed face, to Western art, defining naturalistic portraiture as ‘a physiognomic likeness which is seen to refer to the identity of the living or once living person depicted’.11 While Brilliant and Woodall do occasionally refer to examples of non-figurative or aniconic portraiture, this tends to be in order to reassert the predominance of the naturalistic portrait image.12 In the final pages of his text Brilliant envisages a dystopian future where the existence of portraiture ‘as a distinctive genre’ is threatened by ‘actuarial files, stored in some omniscient computer, ready to spew forth a different kind of personal profile, beginning with one’s Social Security number’.13 The implicit humanism of ‘proper’ portraiture is set against a dark Orwellian vision of the individual reduced to data; writing in 1991 Brilliant could not have foreseen the impact that the internet would have on the way in which we imagine human identity.

In Portrayal and the Search for Identity (2014), Marcia Pointon asks directly (if somewhat rhetorically): Does a portrait have to look like somebody in order to be a portrait?14 Pointon argues that much of what we understand today to be the conventions of naturalistic portraiture originate from Rome in the classical period, where gestural language was adapted from rhetoric for statuary (and hence portraiture); these classical Roman conventions for portraiture largely persist to the present day. Appealing to the work of sociologists such as Erving Goffman, who have shown that communicating and expressing ourselves involve learned gestures that have common meanings within social groups, Pointon suggests that without this shared historical body language portraiture would cease to be meaningful as a social practice.15 Pointon’s argument is perhaps limited: whether gestural or verbal, language is never a static system but a dynamic one, constantly shifting and developing in response to social and cultural change; following this, the language of portraiture must also necessarily be mutable.

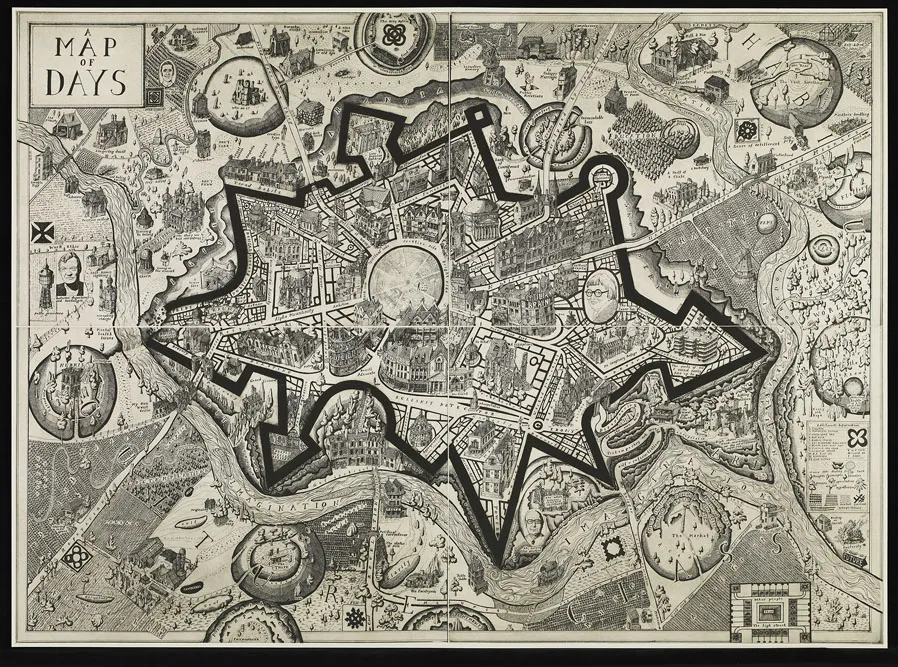

It is this mutability that makes portraiture such a difficult genre to make generalizations about (Pointon herself allows that it is ‘an unstable, de-stabilizing and potentially subversive art’).16 Two examples of portraiture recently acquired by the National Portrait Gallery attest to the genre’s capacity for self-reinvention in response to contemporary concerns. Marc Quinn’s Sir John Edward Sulston (2001) (Figure 1.1) comprises a small stainless steel plate of bacteria colonies covered in agar jelly; these colonies contain parts of the sitter’s genome. (Sulston is a Nobel Prize-winning scientist who worked on the Human Genome Project and was a central figure in the development of DNA analysis.) Physiognomic likeness is rendered irrelevant as individual identity is instead configured through a biochemical dataset that is illegible to all but the expert eye. The second example, Grayson Perry’s Map of Days (2013; acquired 2015) (Figure 1.2), is an atypical self-portrait in the form of a map of a fortified city. The streets are marked for different, often conflicting aspects of Perry’s character; the implication is that the self is not a coherent knowable entity but multifaceted and ambiguous. If Quinn’s bio-portrait suggests an essential, biological model for contemporary identity, Perry’s Map of Days implies that identity is developed via a dialogic relationship between subject and society. Both, however, share with traditional portraiture the fact that they are snapshots of a given moment where the subject has been frozen in time.

Two further examples explore the temporal qualities of subjectivity and recall Brilliant’s anxious pre...