![]()

1

A fine body of men: Recruitment and enlisting for war 1914–18

The First World War American recruitment marching song ‘A Fine Body of Men’ by J. B. Ingle cheerily combined physicality and heroism, ending acerbically with ‘Let’s put in to vigour and vim, Make sure work of this German Spew’.1 In Britain, the fine bodies of British men were under substantial scrutiny, medically, politically and socially as over six million British men were accepted into military service as regular, territorial, volunteer and conscripted soldiers between 1914 and 1918.2 Of all the military conflicts that Britain was involved in, the First World War was unique in that the majority of those who fought served as volunteers rather than professional soldiers or conscripts. At the centre of this zeal for battle lay a combination of targeted recruitment campaigns; societal pressures which forced men to reassess their value, purpose and place within Britain; and an intricate assessment system designed to overtly identify and clarify the ‘best’ men for the job. Throughout the various enlistment phases of the First World War fixation remained on the body. Examinations of men’s bodies meant rejection or acceptance for service. Emulation of the militarized physical ideal impacted on fashion, physicality and social desirability. Between 1914 and 1918 men found themselves constantly challenged to think about their bodies in new ways, including, but not limited to, the practical corporal factors that may have made life in the armed forces seem attractive. Recruitment and assessment practices were also remarkably fluid as the war progressed. In 1918, assessed bodies were viewed, weighed and touched much as they had been in 1914, yet the categories and criteria required for entry had significantly shifted in references to acceptability for service. Hidden within the changing acceptable standards lay a continual contest between subversion and flexibility, as both recruits and assessors attempted to play the system for their own benefit. Enlistment was a complicated and often actualizing experience for many in Britain during the war; therefore, this chapter will examine the propaganda, recruitment process and societal responses to enlistment and service, within the framework of the body, to illustrate how physicality and suitability ultimately came to define an entire generation in the early twentieth century.

No guts, no glory

The ‘rush to colours’ in Britain in the early stages of the war in 1914 was unprecedented. During the Last South African War (1899–1902), the British government had amassed four hundred thousand regular, irregulars and militia men.3 Within eight weeks following the declaration of war in August, British volunteers surpassed this number and kept climbing.4 By the end of 1915, a total of 2,466,719 men had voluntarily enlisted in the army.5 After volunteer numbers began to dramatically dwindle throughout 1915, conscription was introduced in the following year to shore up the gap, though it was never as successful as that first surge of enthusiasm for service. In the final year of the war, only around five hundred thousand men enlisted.6 By comparison, in September 1914 alone, 462,901 men, the highest number of recruits for a single month, joined up.7 After the declaration of war in 1914, regular and territorial men were immediately dispatched. Four of the six standing British Army divisions marched to meet enemy forces in Belgium and Northern France.8 Since the beginning of the twentieth century, the British Army had been undergoing a significant period of improvement and adjustment. Under the direction of Lord Haldane, these reforms meant that the British Expeditionary Force was most equipped and organized of any former British unit; yet in comparison to the enemy they faced the British military was still vastly undermanned.9 Stepping into the breech was Secretary of War Earl Kitchener who managed the most successful public military recruitment campaign in history, first through volunteering before finally introducing conscription. The enacting of the Military Service Act on 27 January 1916 and its successor, the Second Military Service Act, on 25 May 1916 no longer left the decision to enlist to the privacy and agency of the eligible man. Over the course of the year, stipulations continued to relax, as the need for men on the front lines demanded further flexibility. In May eligibility was extended to married men. From August only men who were not physically able or were working in exempt industries, aged under 18 or were over 41 were considered unsuitable for service.10

Physical suitability was the key criteria from the opening stages of the war. This was not a new phenomenon as theorists of masculinity recognize that ‘manhood’ was a long-standing socialized idealization.11 Dawson explains how over the course of the nineteenth century masculinity and militarism became linked within a form of heroic masculinity to be emulated.12 By the outbreak of the First World War, ‘manhood’ had become intrinsically linked within British culture with notions of duty, and physical presentation. Physical size and muscular presentation were particular identifiers of masculinity.13 By the outbreak of the war, this notion of physically demonstratable masculinity was further cemented by the role of the assessment criteria for military and the onslaught of recruitment and propaganda posters which frequently questioned physicality, masculinity and capability to encourage men to enlist. The role in these visual demonstrations of physical idealism and self-critique must not be understated, as they played a crucial role in the soon to occur rush to the recruitment office after the outbreak of war on 4 August 1914. Yet, recruitment initially began slowly with the occurrence of the ‘Pals Battalion’ being the first successful initiative to encourage so many men to enter military service. The ‘Pals Battalions’ were made up of communities of colleagues, teammates, students and neighbours, who sharing a commonality had enlisted together on mass, often retaining elements of their unique method of entry through ‘Pal’s Battalion regiments’, which by designation clarified the men’s associated heritage. Simkins makes it clear that the ‘Pal’s Battalion’s’ were far from a new development as historically Volunteer battalions were a common means of recruitment; indeed, he argues, the Territorial and Volunteer forces owed much to this tradition.14 The innovation came from allowing the forces to celebrate more visibly their shared heritage, and that they were being raised for offensive action abroad rather than domestic security. Successful as this form of motivation was, it was the work of the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee (PRC) which did the most to galvanize enthusiasm for service and the war.15 Formed on 31 August, the PRC recruited a network of local political organizations to act on the behalf of the War Office and encourage men to enlist. This innovative approach resulted in a mass recruitment drive supplemented by the production of 54 million posters and 5.8 million leaflets and pamphlets.16

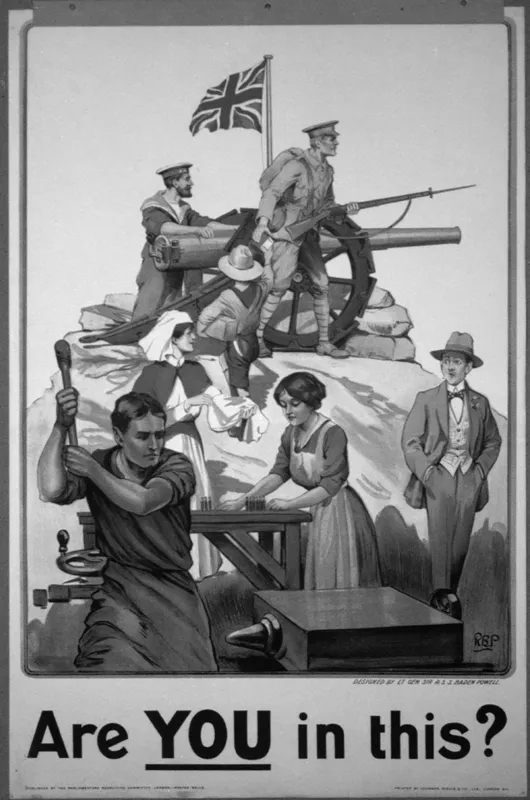

A famous example this campaign is the ‘Are you in this?’ poster created by Scout movement founder Baden Powell in 1915 (see Figure 2). At first glance, the physicality associated with professional soldiering is apparent within the poster. The physically fit and square-jawed soldier and sailor, aided by the brave Boy Scout, immediately draw the eye as they face the enemy steadfast and centre stage. In support of them, the robust hammer-wielding industrial worker and dutiful women workers focus on their tasks with keen determination. All these figures show their bodies caught in moments of activity and convey purpose and dedication to the task in hand. Set aside is the clear abnormality, a diminished man who looks from the sidelines having not contributed himself. This man stands as physical contrast to the other heroic male figures. Dressed unsuitably for war-related activities, he is slope-shouldered and cross-legged. He also lacks the square chin of the other males, and has his hands hidden from view in his pockets. Whereas the hands of everyone else are occupied, empty-handed observer clearly has no purpose. The message of the poster, that the outsider is clearly less of a man, is self-evident, supported by the unsubtle demand underlining the image challenging men to defend their role within the war. The message is transparent: ‘Join up and clarify your masculinity or refuse and reveal yourself as less than a man.’

Posters such as this were often very effective. Albrinck recounts the story of a clerk who felt pressured, by the visual depiction of the heroic men in the posters, to improve his physique before seeking enlistment in order to ensure he measured up to the ideal.17 The importance of the military uniform as factor in encouraging enlistment must not be understated. This is particularly evident as a form of visual appeal that was central to thousands of posters and pamphlets that aimed to pressure men into military service during the First World War, such as the 1915 ‘To the Young Women of London’ poster.18 The 1915 ‘Thank God I Too Was a Man’ was the epitome of this recruitment tactic. Targeting men through women, this poster recruited lovers, wives and sweethearts to strengthen men’s resolve to enlist. Focusing on the physical demonstration of both service and affection, the poster belittled un-enlisted men by determining that the measure of a man was visible by ‘wearing khaki’. The poster boldly pronounces that without a uniform acting as a literal badge of honour declaring masculinity through service to king and country, a man is not ‘worthy’ of a woman’s attention or affection. This interplay on heterosexual relationships and early twentieth-century gender politics is as ingenious as it is insidious. The questioning of a man’s virility and viability for a relationship is made doubly profound by the recruitment of women to internalize and repeat the message. The end of the poster even suggests that a lack of commitment to the country could translate to a loss of interest in a partner, conveying the unsubtle message: ‘If he does not love you enough to wear the uniform, he probably does not love you!’ Desperate times may indeed call for desperate measures; still this approach was extremely incongruous as a method to enlist the male body during the First World War.19

Propaganda focused on physicality was particularly common and effective. Historians such as Michael Brown, Graham Dawson, R. J. Q. Adams and Philipp Poirer have individually shown how men were treated differently in and out of uniform throughout the First World War, with the latterly attired for service frequently receiving a much more welcome and pleasant response than their civilian dressed counterparts.20 As a consequence, some men enlisted with the primary purpose of shedding their socially unpopular civilian dress. Lieutenant Palmer, who served throughout the war in the RAMC, wrote as much within his memoir:

Palmer went on to explain how the homogeneousness of khaki in Britain shifted public perceptions of men, as civilians became heroes by covering their bodies with a military uniform and associated apparel. He explained, ‘The wearing of Kharki [sic] made all men look more or less the same and the populace opened their doors to one and all who wore Kharki [sic]; their rank mattered not one bit, all were heroes and treated as much.’22 For Palmer, as it was for millions of others, the first powerful step away from civilian life was the embracing of the military uniform and the all-important visual demonstration of pride and service to the world. For the state and the British military, appearance was a vital weapon in the recruitment arsenal which was exploited at any opportunity. Throughout the war the masculinized idea of the serviceman’s body was continually depicted and promoted in posters and pamphlets, as well as personified by home front-serving personnel and the recently recruited whose mere presence provided an advertisement for the splendour of military service to the rest of British society.

Clothes maketh the man

Attitudes of awe and a yearning to emulate the uniformed men were common, especially in the earliest stages of the war. This is particularly visible in the dia...