![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Religion and Ritualized Belief

MARY HARLOW AND LENA LARSSON LOVÉN

In the ancient world, religion was an integral part of the everyday. Religious and ritual practice was not confined to a single day of the week, or a specific area, it was embedded in every part of life and action. Ancient Greeks and Romans lived in a world full of gods who could choose to either protect or harm individuals or whole communities. They were appealed to, appeased, worshipped, and honored in a range of rituals, festivals, and secret mystery cults which operated on both a public and a private level. Worship could take the form of large, public festivals which might involve animal sacrifice, drama, processions, and feasting which affirmed the community, or could simply be a private, personal offering such as a small gift of grain to a particular god at a small altar in one’s own home. Sanctuaries to the gods were placed in cities, such as on the Acropolis in Athens and on the Capitol in Rome, where they might form part of a temple complex. They could also be found at in the agora and fora of ancient towns, at crossroads, at corners, by rivers and water generally; temples and sanctuaries were also placed in the countryside, often in quite remote areas such as mountains, or in areas associated with particular deities or events. Small shrines to local gods are found across the ancient world in both urban and rural settings. Put very simply, ancient religion was about performing the appropriate rituals to keep the gods on side, and as such it was both a state and an individual affair. An individual took part in these rituals on his or her own, or as part of a family, or part of the community, or in groups divided by age and/or sex. For the ancients, the supernatural was ever-present and everywhere. To the modern eye, which tends to have a very different view of religion, ancient beliefs and practices are often perceived negatively as “superstition” or “magic.” In antiquity, “magical” practices were very much part of the religious everyday from the arcane and dangerous curses sworn to cause harm to the seemingly more mundane amulet used to ward off evil.

In many cultures, hair itself, hair practices, and behavior surrounding hair signify a complex of intertwined, culturally specific markers of gender, of age status, of ethnicity, of sexual status, of belonging, or of exclusion. The hair’s potential for manipulation and its ability to constantly replenish itself allow it to serve as dedications, as metonymic symbols, as charms, and sympathetic magic.1 Hair, or lack of it, can cover a multiplicity of meanings: a shaved male head, for instance, may represent punishment or slavery in one context, or devotion to a particular deity in another. In a woman a shaved head may mark her as a bride in Sparta, as a slave in Rome, or as an extreme ascetic in early Christianity—it may also, of course, also be a practical cure for head lice!2 In all these cases, apart from the head lice, the head and hair act as symbol for the social and/or ritual situation of the individual. The control of hair, or indeed, its opposite, wild, uncontrolled hair, are useful symbols for the expression of rites of passage, the movement from one status to another,3 or to express moments of heightened emotion and crisis. It is in these contexts that we commonly observe the ritual use of hair in ancient society. Similarly, in a religious context, a priest or priestess may possess a particular hairstyle in order to place them outside the ordinary and into the sacred realm. Many of the ritual practices of antiquity have origins in the mythical past which have been translated into the social and religious customs of society. This chapter examines ways in which the male and female head and hair are integrated and manipulated into the ritual behavior of ancient societies

HAIR AND AGE-RELATED RITUALS

Hair is a very clear marker of biological and physiological stages of life; the growth of secondary hair accompanies puberty for both males and females, and at the other end of life, thinning or graying hair is also common to both sexes while complete hair loss and baldness is more common in men. The transition into adulthood is one of the most significant stages of life in most cultures and it is no surprise to find it hedged with rituals, many of which involve the most obvious physical markers of change, hair. Moving from adolescence to adulthood can involve a number of stages and might depend on the rank and status of the individual’s family in society and, in antiquity, would certainly differ in the cases of boys and girls.4

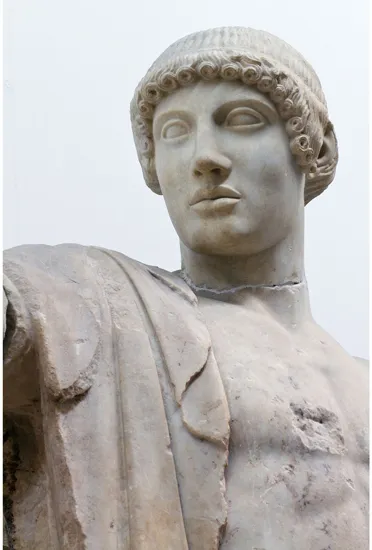

Ancient Greek culture in the period this volume covers has many examples of boys and men growing their hair, or particular locks of hair and cutting it as part of cult practice or in fulfilment of a vow, but as David Leitao has argued, as hair grows naturally, “a normal practice can become invested with particular power and symbolism if done in a ritual context. It blurs the boundaries between the everyday and ritual space.”5 It is this blurring of boundaries and the embeddedness of Greek religion into every part of life that makes ritual hair practices hard to identify unless ancient authors specifically discuss them. Growing hair also takes time, and if grown to fulfil a particular vow, it is unclear whether the individual is in a liminal state while the hair is growing, with the growing being part of the ritual, even though he is presumably going about his daily business. Again, there is a mingling of ritual and the everyday, or rather, ritual forms part of the everyday.6 That said, “growing hair for the god” was a common practice in the Greek world and appears to happen at a number of occasions and ages, but it was a public part of the male entry into adult life in many Greek states. Several gods were associated with male maturation rituals, including Herakles, Dionysos, Hermes, and Apollo. Apollo is often associated with the ideal of youth, and in iconography can be recognized by his long, boyish hair and beardless face (Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1 Detail of Apollo from the west pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. Photo Alamy BNMD7Y.

In classical Athens, an important event in the lives of citizen boys was the ceremony by which they entered their father’s phratry. For citizen boys, the enrolment into the phratry was essential to secure inheritance rights. This traditionally happened during the annual festival of the Apatouria. On the third day of the festival, the Koureotis, consisting of a number of ceremonies took place marking different stages in the life course, depending on the individual concerned. For boys just entering the phratry, an animal sacrifice was accompanied by ritual hair cutting (koreion) which marked the first part of the boy’s transition into adulthood. This was a public ceremony, performed in front of other members of the group and established a young man’s credentials for entering full citizen life and its responsibilities, and perhaps took place for a cohort of boys aged between fourteen and eighteen.7 Other Greek states had similar ceremonies in which hair cutting accompanied rites of passage rituals.8 After these ceremonies the boys had short hair which set them apart from younger members of society. It is unclear exactly how the hair on these youths might look, it might never have been cut since birth, or it may be that particular locks were never cut, while the rest of the head conformed to local styles. The specially grown locks are known by a number of terms (skollos, konnos, mallos, krôbylos) and in iconography it appears they could be topknots, sidelocks, backlocks, and even, as in Figure 1.2 of Apollo from Aphrodisias, frontlocks.9

FIGURE 1.2 Head of Apollo from Museum of Aphrodisias. Photo Alamy CW5DYN.

Plutarch tells the story of Theseus who went to Delphi to celebrate his coming of age and cut off just the front locks of his hair. This style was subsequently named Theseis after him and, according to Plutarch writing in the early second century CE, recalled the heroic, war-like, Homeric Abantes who were famed for close fighting and cut their hair to deny the enemy a chance to hold on to it.10

Pausanias, a second century CE author with a great interest in the local cults of provincial Greece collected a number of examples, many of which were no longer extant in his own time. He noted a dedication of a boy who cut his hair for the river Kephisos,11 and recorded that at Corinth boys no longer cut their hair for Medea’s daughters or wore black clothes:12 David Leitao has collected examples from across the Greek world which demonstrate the range of contexts in which hair might be dedicated, and the performative potential of these dedications which can highlight family relationships, primarily fathers and sons, but also mothers and sons, and brothers. And, that almost all of the examples appear to be in the context of coming-of-age rituals.13

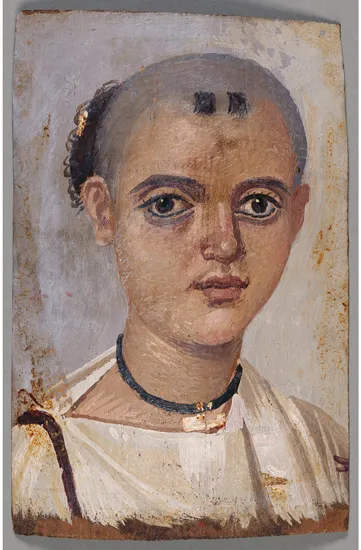

In Pharonic and Greco-Roman Egypt some young boys are shown with shaved heads and “Horus lock.” Horus was the son of Isis and Osiris and a symbol of youth. The wearing of the lock may simply indicate youth, but it can also suggest dedication or devotion to Horus, and has been interpreted as offering protection to the child. In Figure 1.3, dating to the mid to late second century CE, a young boy is shown with his head shaved, apart from two tufts of hair at the front and the Horus lock, decorated with a gold pin. Unfortunately as this is a portrait of the child after his death, his Horus lock could not protect him from the ever-present dangers to life in antiquity.14 Jane Draycott’s recent study of votive offerings highlights the Egyptian practice noted by Herodotus of parents shaving a child’s hair and making a dedication in gold of silver, equivalent to the weight of the hair. This ritual continued into the Roman period.15

FIGURE 1.3 Mummy Portrait of a Youth (150–200 CE), encaustic on wood, 20.3 × 13 cm (8 × 5.12 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA.

In the Roman world, while children are traditionally shown with longer hair, the cutting of cephalic hair is not such a key element in the male transition to adulthood; in contrast, the focus is on the first real shaving of the beard. The appearance of facial hair in young men also marked the beginning of a new stage of life and the emergence of sexuality. Greek culture saw the first downy growth of young men as particularly attractive and erotic and for male lovers this marked the beginning of the end of acceptable homosexual relationships. The appearance of a full beard and shaving marked the arrival of adulthood in which the man would become the active lover rather than the passive beloved.16

In the Roman world the shaving of the first beard was not done until a full beard could be grown. So adolescents with downy facial hair formed a particular social group, not yet full adults. These “beardless” youths could still be subject to immoral influences and behave recklessly.17 As their facial hair grew and matured, so the young men were expected to behave more like responsible adults, but until they could shave their first beards their position in the adult world was insecure. The young Octavian, who became the Emperor Augustus, was leading troops to avenge his adoptive father, Julius Caesar, by 43 BCE at the age of nineteen, despite the fact that he did not shave his first beard until 39 BCE. To compensate for his perceived youthfulness he aligned himself with Apollo, the youthful, beardless, and long-haired god, and perhaps for political expedience, Octavian remained clean-shaven after his first shave, retaining the association with Apollo. Octavian’s first shaving of the beard was accompanied by some ritual, and he granted all citizens a festival at public expense.18 The young emperor Nero, another great showman, accompanied his first shave with a sacrifice of bullocks, and placed the shavings in a golden box adorned with pearls and dedicated it to the Capitoline gods.19 Nero possessed a family cognomen of Ahenobarbus, meaning bronzed beard, which, in the family mythology, was granted to an ancestor who had his cheeks stroked by the Dioscuri after the Battle of Regulus in 496 BCE.20 While in reality social behavior does not necessarily change with social expectations or with hair growth, a young man was treated differently once his beard was shav...