![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Religion and Ritualized Belief: Evangelical Hair

MISTY G. ANDERSON

Long before Tammy Faye Bakker’s teased up bob, Jan Crouch’s gravity-defying mane, or the self-proclaiming toupée of Ernest Angley, evangelical hair was a thing. It’s fair to say that hair’s religious and political journey through the Reformation and into the modern world began when Martin Luther let his hair down in 1521; after burning Pope Leo’s papal bull, denouncing indulgences and private mass, and writing The Judgment of Martin Luther on Monastic Vows, Luther grew out his Augustinian tonsure. While Luther’s hair may not have been especially fabulous, it was a sure and visible sign of the Reformation and the cultural fact that Christian hair would, for some time to come, signify religious identification across a Protestant to Roman Catholic spectrum of meanings, with the tonsure at one pole and an infinite variety of delight and disorder at the other.

The particular “thing-ness” of hair itself as of the body but not in it provided an arena for doctrinal debates about sensation, pleasure, and worldliness. What did it mean, for instance, to be in this world but not of it? How should Christians read Paul’s confusing declaration in 1 Corinthians 11:6 that a woman should have her head covered in church or cut it all off, even though that would be both a shame and shameful? Stranger yet, how should they read his pronouncement a few lines later that the hair itself is a woman’s glory and her covering? In the Bible, hair is the source of Samson’s strength, the towel with which a weeping woman dries her tears from the feet of Jesus, and the means to police women. Hair occupies a liminal space in the Christian religious imagination, residing somewhere between the human and the superhuman; it is both perfectly natural and hopelessly excessive. Men’s hair, which occupies the most attention in religious debates and conflicts about hair in the long eighteenth century, sits on the sensual paradox of Christianity, torn as it is between incarnation and asceticism.

The larger debates about pleasure, happiness, and choice that frame the significance of hair from a Christian point of view heat up with the Reformation, which makes matters of individual conscience the new standard for religious identity. The rhetoric of conscience grounds the subject known as the modern individual, whose freedom of choice and capacity for conscious choice is celebrated and defended by theories of liberalism.1 The discourse of freedom can, however, be reduced to consumer and fashion choices. The “unavailability of personal style” that Jameson argues is the key feature of postmodernity’s mediated pastiche harkens back to and runs through the limited protest that hair has provided.2 As Srinivas Aravamudan avows in “Subjects/Sovereigns/Rogues,” texts have many ages; so do hairstyles, and the hermeneutic if not defiantly nonlinear temporality of Christian experience makes the recursiveness of hair lengths and styles a kind of second coming. What I am calling “evangelical hair” draws on both the Greek euangelion, “good news,” and Luther’s Latinization, evangelium, the churches appearing after the Protestant Reformation. This dual formation of the evangelical as both the proclamation of good news (always already yet to come) and the sign of difference or rupture captures the semantic volatility of hairstyles. Understanding the discursive as well as recursive significance of hair, as both langue and parole, in the uncomfortably but necessarily shared modern territories of religion and politics, helps us see how eighteenth-century evangelical hair functioned as both a signifier in formation, growing, and changing, and a sign of the primitive or backward-looking believer who makes the enlightened modern possible. The believer’s hair, whether Puritan, Leveller, or Methodist, differentiated the faithful from a consuming modernity. At the same time, the big, wide, and rapidly changing world of eighteenth-century fashion mediated the sociable, messianic call of consumer capitalism, in which sporting the next great look, style, or “do” could mean that you might have “it,” that “pronoun aspiring to the condition of a noun […] the easily perceived but hard-to-define quality possessed by abnormally interesting people.”3 Taking religion and hair this seriously might help us trace the braid of sensuous, ascetic, and religious meaning that began with the tonsure, worked through the Roundheads, then the Methodists, and eventually, gave us televangelist hair. Rhetorics of personal affect, freedom, and autonomy from papal control that defined Protestant, post-Reformation hair quickly made clear that one’s hairstyle, especially for men, was subject to more than occasional conformity. As Puritan and later Methodist protests became hairstyles, the look that was supposed to be the sign of the most deeply held commitments proved to be yet another imitable style.

PURITAN HAIR

The Restoration only exaggerated what had been true since James (VI of Scotland and I of England) began sporting his natural locks: the court was home to both luxury and luxurious hair. The courtly locks of the Stuarts before and after the English civil wars suggested an erotic excessiveness that sparked Puritan protests, including low-church bowl cuts for men and modest caps for women. The stakes of these Puritan and courtly styles were so high that even talking about someone’s hair in the seventeenth century was potentially actionable. The widely invoked insult “roundhead,” a reference to the close-cropped hair of Parliamentarians who fought against Charles I, was a punishable offense in Cromwell’s New Model Army.4 Roundheads were most often Puritans of various denominational stripes, often Presbyterians with a few of the more radical factions such as the Levellers and the Diggers. But the significance of hair was neither straightforward nor merely a matter of style. We know that some covenanters (Scottish Presbyterians) like the Rev. Alexander Peden wore wigs that would have looked like a full head of natural hair. At least one survives at the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland, Edinburgh, showing extreme wear in the spots where Rev. Peden’s hat was pulled on and off.5

The short version of seventeenth-century British hair is that short hair (on men) meant Puritan allegiance, until Laud stole the style. The classically Puritan case against long hair came from Puritan divines and doctrinaire stylists like Thomas Hall, who denounced men’s hair “when it is so long that the godly are thereby grieved, the weak offended and the wicked hardened.”6 The full title of Hall’s treatise is worth reproducing in all its glory: The Loathsomnesse of Long Haire: or, a Treatise Wherein you have the Question stated, many Arguments against it produc’d, and the most materiall Arguments for it retell’d and answer’d, with the concurrent judgement of Divines both old and new against it. With an Appendix against Painting, Spots, Naked Breasts, &c. As a preface, Hall included the cautionary verse, “To the Long-hair’d Gallants of these Times,” attributed to “R.B.” (probably Robert Bolton), which urges:

Go Gallants to the Barbers, go,

Bid them your hairy Bushes mow.

God in a Bush did once appear,

But there is nothing of him here.

Here’s that he deeply hates: beside,

That execrable sin of Pride;

Here also is that Felony:

Nay, Is not here Idolotry?

Such Bushes daily intervert

The time that’s done to th’better part:

[…]

Those pour sweet powders rather strow

Upon the ground on which you goe,

Than let them be so vainly spent

Upon an haughty Excrement.

Forget not that your selves are dust,

And the Times tell your Heads they must

Their powders into Ashes turne,

And teach their Wantonnesse to Mourne.

This cautionary verse and call to humility compares the lavish and unholy “bushes” of Cavaliers to the burning bush through which God spoke to Moses. His connection between hair and “excrement” refers both to the idea that hair is a form of excrement and to the use of excrement as a popular cure for baldness in the seventeenth century. For these and other reasons, Hall would probably have disagreed with that truism from the American South, “the higher the hair, the closer to God.”

The psychological boundary that hair represents, in both its vitality and its morbidity, breaks open in Hall’s footnote about a click-bait-worthy new Polish hairstyle, “Enough to make all Lands afraid, / And your long dangles stand on end?” A tightly packed “L” of marginalia, in the manner of the Geneva Bible, The Pilgrim’s Progress, and many other Puritan texts, glosses the tale:

most loathsome and horrible disease in the haire, unheard of in former times; bred by modern luxury & excess. It seizeth specially upon women; and by reason of a viscous venomous humour, glues together (as it were) the haire of the head with a prodigious ugly implication and intanglement; sometimes taking the forme of a great snake, sometimes of many little serpents: full of nastiness, vermin, and noisome smell: And that which is most to be admired, and never eye saw before, pricked with a needle, they yield bloody drops. And at the first spreading of this dreadfull disease in Poland, all that cut off this horrible and snaky haire, lost their eyes, or the humour falling downe upon other parts of the body; turned them extremely. (n.p.)

Hall attributes the story of the Polish stigmatic snake-dos to puritan Robert Bolton’s Hercules Saxonia; it also appears in Mr. Boltons last and learned worke of the foure last things: death, judgement, hell, and heaven (London, 1633). The story is a compact blend of a Medusa tale, manufactured stigmata, and anxiety about excessive, serpentine coifs and the hair products that held them up. The phallic headdresses of these Polish women did not need to await Freud for analysis; the powerful effects, including blindness and mysterious bodily ailments, track along with the mortifying power of Medusa and the reversal of the power of the gaze that she represents. Grammatically, the hairstyle is represented as a “disease,” not a choice, but the damage is done to those who cut off the hair, reeking with pomatums and blood. These Polish serpentine styles damn excess on the heads of men as well as women as messy, smelly, and on the side of death.

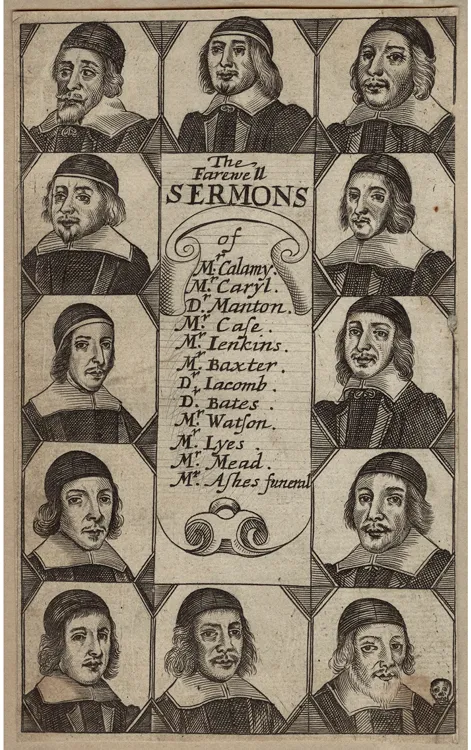

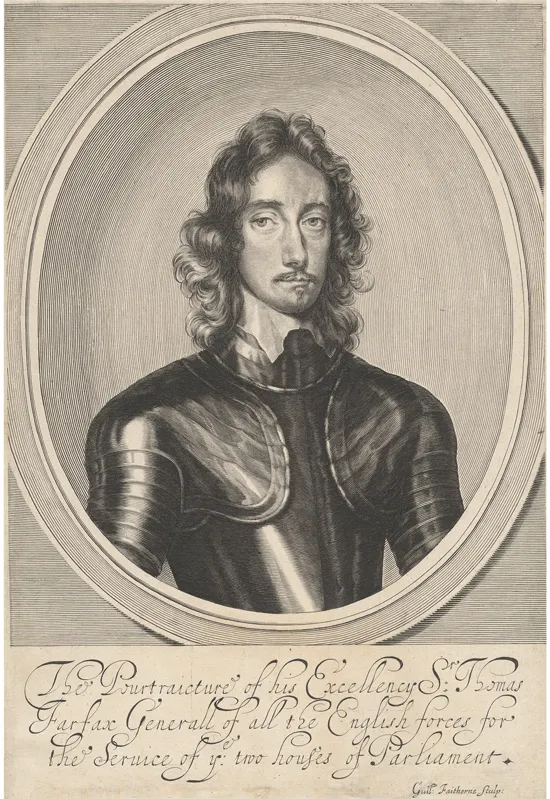

The most important reversal in the seventeenth-century history of hair was, however, the Roundheads themselves. Short hair as a Puritan objection to Cavalier and courtly style met with its own counterreformation just a few years after Hall’s treatise when Archbishop William Laud instructed all clergy via a 1636 statute to wear their hair short. Many Puritans, especially higher ranking ones such as Sir Oliver Cromwell and Sir Thomas Fairfax, rebelled against this Church of England edict and grew their hair. Many others followed these “Roundhead” leaders and grew their natural locks, thus quickly confusing the visual economy of hair length and religiopolitical allegiance (Figures 1.1 and 1.3).

FIGURE 1.1: Title page to an edition of The Farewell Sermons of the Late London Ministers (ca. 1662–1663). © National Portrait Gallery, London.

FIGURE 1.2: Robert Walker, Oliver Cromwell (ca. 1649). © National Portrait Gallery, London.

FIGURE 1.3: William Faithorne, Sir Thomas Fairfax (ca. 1646). Yale Center for British Art, Yale Art Gallery Collection. Gift of Edward B. Greene.

Andrew Marvell, Cromwell’s protégé, poet, and eventual MP, is another case of long Parliamentarian locks. But the paradox of Roundheads with long hair is nowhere clearer than in the portraits by Samuel Cooper and Robert Walker showing Oliver Cromwell’s head, richly adorned with his own long hair, an image that was also used on various medals (Figure 1.2).

The ups and downs of Puritan styles help to contextualize Milton’s complex personal and aesthetic relationship to hair. The earliest image we have of Milton (Figure 1.4), as Stephen Dobranski observes, is the poet at ten years of age “with closely cropped auburn hair,” which suggests “he was exposed to Parliamentarian ideas as a young man; according to Milton’s widow, her late husband’s schoolmaster, ‘a puritan in Essex,’ had ‘cutt his haire short’ (Aubrey 2),” in keeping with the cropped Puritan style of the early seventeenth century.7 Portraits of the adult Milton, including the William Faithorne engraving, show him in long and presumably natural hair (Figure 1.5). Milton lived through the period of changing hair lengths for the faithful, which, by the actual Restoration, had thoroughly confused the issue, even as the term “roundhead” persisted.

FIGURE 1.4: Giovanni Battista Cipriani, John Milton (1760). Yale Center for British Art. Gift of David M. Doret in memory of William Ferguson.

FIGURE 1.5: William Faithorne, John Milton (1670). © National Portrait Gallery, London.

More significant for the history of evangelical hair, however, are Milton’s characters, particularly Adam, Eve, Lycidas, and Samson. Lycidas’s “oozy...