![]()

1

On Resonance

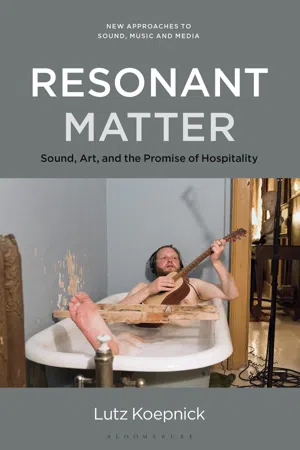

Figure 1.1 Ragnar Kjartansson: The Visitors, 2012 (The Porch). See also Plate 2.

Echo’s Legacy

A piano whose sounds animate a nearby tuning fork. Metallic surfaces covered with sand that display wonderous figures when subjected to the movements of a violin bow. An aging engine causing your entire car to vibrate. Images that register the impact of strong magnetic fields on bodily organs. Prehistoric cave dwellers who use reverberant spaces to draw lines on rock formations. Modern-day musicians falling into each other’s song and attuning their singing to the rhythms of a percussionist. A person agreeing with another person through empathy rather than rational argumentation. A poem whose words echo in my memory as if I had written or spoken them myself.

We have come to describe phenomena such as these, in all their difference, as examples of resonance: as instances in which something is affected by the vibrations, intensities, motions, or emotions of something else, as events in whose context one object causes another object to take on its own trembling. Inspired by Ragnar Kjartansson’s The Visitors (2012), this book explores resonance as a model of art’s fleeting promise to make us coexist with things strange and other. Approaching the sounds of installation art as a unique laboratory of hospitality amid inhospitable times, we will follow the echoes of distant, unexpected, and unheard sounds in twenty-first-century art to reflect on the attachments we pursue to sustain our lives and the walls we need to tear down to secure possible futures. As this book begins its journey, however, it is important first to discuss the often wildly different uses of the term “resonance” in past and present and complicate given assumptions, as they exist at least in everyday language, that resonance describes something unquestionably valuable or desirable in and of itself.

Consider the famous collapse of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge in 1940, triggered by peculiar wind conditions that caused the 2,800-foot construction to vertically oscillate beyond control. Physics textbooks typically present the collapse of the bridge as an example of forced vibration, the way in which one object or system—in this case, the wind—can force a neighboring object into large vibrational motion. Even though such transfers of energies may not produce any audible sound, physical engineers consider forced vibration as an instance of mechanical resonance, the term describing occurrences in which objects or systems respond to oscillating forces whose frequency is close to or identical with their own natural frequency.

No human was killed in the disaster at the Puget Sound. Its only victim was Tubby, a cocker spaniel owned by Leonard Coatsworth, the news editor of the Tacoma News Tribune. Coatsworth had been the last person to be on the bridge before its violent swaying brought it down. Here is his report of the events of November 7, 1940:

Around me I could hear concrete cracking. I started back to the car to get the dog, but was thrown before I could reach it. The car itself began to slide from side to side on the roadway. I decided the bridge was breaking up and my only hope was to get back to shore. On hands and knees most of the time, I crawled 500 yards or more to the towers. . . . My breath was coming in gasps; my knees were raw and bleeding, my hands bruised and swollen from gripping the concrete curb. . . . Safely back at the toll plaza, I saw the bridge in its final collapse and saw my car plunge into the Narrows. With real tragedy, disaster and blasted dreams all around me, I believe that right at this minute what appalls me most is that within a few hours I must tell my daughter that her dog is dead, when I might have saved him.1

Though his experience was no doubt traumatic, Coatsworth understood how to retell the event engrossingly and dramatize his story. His report is rich in detail and texture, conjures compelling images to focalize his narration, seeks to capture the bridge’s destructive oscillations with the rhythm of his syntax. Switching from past to present tense, he in the end effectively draws the reader even into his own feelings of fear, failure, and guilt. Literary criticism has various concepts at hand to analyze Coatsworth’s strategies of emplotment, of appealing to the reader’s affect and emotions. In everyday parlance, however, we have come to call Coatsworth’s mode of telling the events of November 7 as an effort to make his experiences resonate with ours. He evokes striking images, memories, and emotions, not to offer a merely descriptive account of the event but to touch upon our affects and activate our empathy. To establish emotional resonance, for Coatsworth, is to invite strange readers into his story’s space and share his harrowing memories in all their vibrancy.

The concept of resonance abounds with perplexing ambiguities and metaphysical subtleties, so many in fact that it appears virtually impossible to identify the concept’s common denominator. At first, the term seems to belong firmly to the realm of audible sensations. “Resonare” in Latin originally meant the same as the equivalent in ancient Greek: “to resound” or “to echo.” In Ovid’s retelling of Echo’s myth, Echo was of interest because of her unconditional but largely muted attachment to Narcissus, while the nymph’s sad fate—the reduction of her voice to pure sonority, the shriveling of her skin, her final turning into stone—offered ample warnings not to replay what had caused Juno’s initial wrath, namely Echo’s boundless chatter. There can be little doubt about the masculinist framework in which Ovid’s story has been told. Cursed to serve as a mere resonance chamber of the world, Echo’s ability to resound the sounds of others certainly expressed the vitality, the utter attentiveness, of her emotions. Her inability to produce new sounds and utter words on her own, however, at the same time marked her downfall: unmitigated resonance could not but result in death.

The resonant life and death of Echo, a male fantasy of unique dimensions, strangely haunt today’s uses of the term. Her being torn between the costs and blessings of living a life anchored in resonance has become our continued toggling between seemingly exclusive scientific and metaphorical, causal and affective, determin istic and non-deterministic, materialist and aesthetic understandings of the term. Mechanical engineers studying what aeroelastic flutter did in 1940 to the Tacoma Narrows Bridge use the term “resonance” to explain the physical world as a transparent dynamic of linear causes and effects, of measurable transactions and transductions, of identifiable stimuli and predictable responses. In the vocabulary of humanists as much as of everyday language, on the other hand, the concept of resonance serves a very different purpose: the term is typically used to describe the fuzzy landscapes of human emotions and affects, the complicated dramas of soul, body, mind, and empathy as they—like Coatsworth’s retelling of the events of November 7—stretch out to, yet always fear not to touch exhaustingly enough onto, the lives of others. In stark contrast to scientists speaking about the physics of resonance, everyday situations resort to the concept whenever we cannot name exact causes and logical influences, whenever certain emotions, images, thoughts, or memories somehow chime with those of others, the term’s presumed vagueness being its very strength, a reminder that the human might exceed logic, causation, and predictability.

Mechanical engineers claim Echo’s resounding legacy as much as atomic particle scientists, molecular chemists, and sound technicians in order to name vibrational transfers between different objects and materials. For some, such transactions might be accompanied or even centrally concerned with audible sensations. For most, they aren’t. More importantly, however, none of the scientific uses of the term seem to mesh with its metaphorical and affective understandings and the currency resonance has assumed in everyday language, in particular during the last decade or so. Whereas for some the concept offers a tool to soberly explain and analyze observable effects, for others resonance provides a lens of interpretation and speculation, a figure of thought meant to explore what transcends observation and analysis and cannot but remain inherently ambivalent. It is therefore tempting to suggest that C. P. Snow’s famous 1959 distinction between the modern cultures of science and the humanities rips right through the concept of resonance as well,2 with the term’s exclusive applications documenting a profound absence of shared standards, methodologies, approaches, and values in different branches of contemporary knowledge production and society in general, between STEM and the aesthetic.

But wait. Your map of resonance might not be mine, yet even once divided cities and countries have managed to overcome cold war divisions and thus avoided repeating the narcissistic isolation and self-destruction of Echo’s beloved. Does resonance know of some common ground beyond its discursive divisions? A ground unsettling Snow’s two cultures? Neither mechanical engineers nor literary critics, so much is clear upfront, will disagree that resonance is a deeply relational concept—that it takes at least two different bodies, forces, materials, subjects, or objects to trade certain vibrations. So let me spin this a little further.

To resonate is to echo with something, is to enable or make an echo. It is to give an echo to something, to let something come and arrive, let something in and take place, so as to enable the kind of connection, attachment, and reciprocity we call resonance, whether it is strictly physical or bedazzlingly affective in nature. Cursed with, as Juno had put it, a voice much shorter than her tongue, Echo fell in love with and furtively followed Narcissus’s footsteps.3 Though unable to lend words to her passion, she certainly was neither numb nor dumb, neither void of agency nor closed to being touched by her immediate surrounds. Unlike her self-optimizing beloved, Echo’s power to resound rested on her ability to get herself entangled and not to accept the borders, lines, distances, and differences that separate bodies, minds, objects, and subjects. She could only resound and resonate because she knew—stealthily or not—how to lean toward the other and thus allow this other to affect her.

Echo’s story has, for many good reasons, little currency in #MeToo times.4 And yet, when read against the grain, Echo’s fate communicates claims and insights that are worthy of being remembered and recuperated. Neither hearts nor bridges begin to tremble if they do not bring something to the table, if they do not open a door and thus offer a space to that which enters their perimeters and makes them vibrate. The analogue to Echo’s unwanted, but nevertheless extraordinary, receptivity to the world is what mechanical engineers call the natural frequency of a given material or object, the inherent pulsation of all matter. Similar to how caves offer specific features and properties—affordances—to enable the wondrous effects of echoes, so do objects resonate with the vibration of other neighboring objects because they embody more than mere passive receptacles. Like good listeners listen out to the world around them, material objects, minds, and emotions resonate with others because they owe certain agential powers all of their own. They can take on the vibrations of other objects or forces because they have the capacity to affect the world themselves, to lean toward possible encounters and entanglements without necessarily pursuing any explicit purpose or strategic design.

Resonance, then, is both a strictly scientific and an unapologetically metaphorical concept. It is about measurability as much as it is charged with poetic vagueness. For some, it describes observable facts. For others, it provides a figure of thought, meant to evoke what exceeds observation. What all the word’s different uses share, however, is to present resonant matter, the matter of resonance, as a condition in which one entity allows and welcomes another into its space and times without putting up fences and resistances, without expecting, anticipating, or generating some sense of reciprocity. Though resonance designates modes of attachment categorically clear to some and productively fuzzy to others, at heart it identifies relationships between dissimilar agents in which the strange, foreign, and other can interface with the known, familiar, or inherent across their very differences.

In the realm of human affairs, we call such openness hospitality: a condition requiring, following Derrida’s reading of Kant, “that I open up my home and that I give not only to the foreigner (provided with a family name, with the social status of being a foreigner, etc.), but to the absolute, unknown, anonymous other, and that I give place to them, that I let them come, that I let them arrive, and take place in the place I offer them, without asking them either reciprocity (entering into a pact) or even their names.”5 Resonant matter, in all its different versions, is hospitable matter—matter that enacts or entertains processes of unconditional hospitality. It asks no questions, draws no pacts or agreements upfront, expects no tradeoffs for letting the other’s vibratory energies come, arrive, and enter. Like a generous host, it simply takes on the vibrations of the other. We don’t need to look at the Tacoma Narrows Bridge in order to remind us of the fact that gestures of absolute hospitality can often produce devastating effects. Yet the bridge’s catastrophic fate offers a stark reminder that resonance, like absolute hospitality, is agnostic to what is given place; that we, in assessing the power of resonance as a structure of hospitable entanglement, should not naively think that it will automatically put forth the good and desirable; that resonant vibrations, even when at their most mechanic and deterministic, are fundamentally ambivalent in ...