![]()

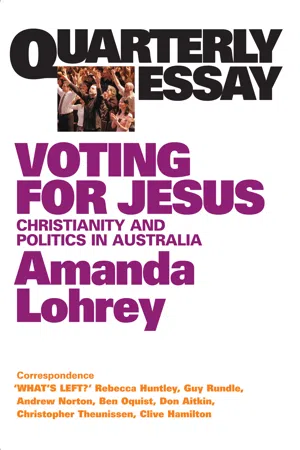

VOTING

FOR JESUS

Christianity and

Politics in Australia

Amanda Lohrey

THE COOL GIRLS

It’s a dark wet afternoon beneath one of those Sydney skies of low turbid cloud and I am sitting in the bedroom of a sixteen-year-old schoolgirl whom I’ll call Abby. Abby has invited her friends Rebecca and Skye to join us and we are here to talk about the spirit. For some time Abby’s parents have been telling me about their daughter’s involvement in the Hillsong Church and her regular attendance at one of its youth groups, and Abby and her friends have agreed to be interviewed on the subject of their religious convictions. These girls interest me because none of them has Christian parents. At the tender ages of fifteen and sixteen they have found their own way to faith. They are the new foot soldiers for Jesus.

Abby’s room is a conventional teenager’s room. There are no altars or crucifixes, or any kind of religious iconography; just a double bed draped with a mosquito net, some silk cushions, posters, a guitar upright in the corner, a desk and computer, ornaments, books and a rogue’s gallery of photos on a posterboard on the wall. The usual. Nor could these three girls be described as pious. These are cool girls: good-looking, into pop music, and with a dynamic circle of friends. They are also scholastically bright, as their school results attest. But they strike me as being very different in character, one from another. Abby sits demurely at her desk chair. She is pretty and she is serious; quiet and thoughtful. Skye leans against the old fireplace and seems restless. She says least of the three but soon reveals an insouciant wit with a gleam of take-it-or-leave-it confidence in her eye. But it is Rebecca, sprawled on the bed, who is the forceful centre of the group. A handsome and intelligent girl, she impresses me as articulate and a born organiser; a kind of young Athena of zealous character sprung fully formed from, in this case, the head of Jehovah. It is Rebecca who is the most wary of me. She knows that Hillsong has been in the news recently and suspects that I have come to run some kind of exposé; to set her up.

And maybe I have.

I explain to the Hillsong girls that I’m writing for the Quarterly Essay series and they agree to let me tape them. What is immediately interesting is how honest and open they are, and how comfortable they appear in expressing their differences in front of one another. Clearly they have discussed the issues I raise before, among themselves, and are willing to accept that friends may differ. Despite disagreements on, say, abortion, they are comfortable in speaking their mind, and to co-exist, for now, in the same Christian youth group because what matters – fundamentally and above all “issues” – is having a relationship with Jesus. Jesus is the key to all things and the test of every action is “What would Jesus do?”

I ask Abby if she can remember when she first became interested in Jesus. “Well,” she begins, “I started going to Youth [Hillsong] about two years ago because some of my friends were going and they said it was fun and that’s when I got interested in Jesus. I believed in God before that and I believed in Jesus but I didn’t have a relationship with him.”

You feel you now have a relationship with him?

“Yes, it’s like, it’s the relationship with Jesus that they offer you, not the religion. It’s more like, do you want Jesus to come into your life and to love him?”

This is my first encounter with a distinction that is to come up again and again, the difference between having a personal relationship with Jesus and “religion”. It soon becomes clear that in Abby’s mind religion is a set of rules and institutional practices that she does not relate to and that can seem arcane, musty and even comical (later in the course of our conversation she will indulge in witheringly satirical mimicry of one of the Christian ministers who recently visited her school).

Jesus, on the other hand, is something else. “Like, ultimately he died for me and I think that’s really awesome.”

I ask the girls what “God” means to them. Is Jesus a form of God?

Abby: “There’s a God and Jesus is his son. God sees the earth is dying and he’ll give a part of himself in Jesus to save the earth. Jesus is God on earth, God in a form we can cope with.”

God in a form we can cope with? This strikes me as quite a sophisticated thought. And I note the use of the present tense, that the earth is perpetually in a state of dying and the gift of Jesus and his redemption of the earth is a perpetual, ongoing process, not a one-off event that occurred two millennia ago.

I turn to Rebecca, who tells me that her older brother has been her primary influence. “He began attending a Baptist church about five years ago and then he heard about Hillsong and started going and he told me about it.”

Why did your brother start going to the Baptist Church?

“Well, because initially the guy who runs the Baptist Church was teaching scripture at our school and they used to give out free hot chips on a Friday and my brother started going because of that, and that’s how he got started.”

The girls look at one another and break into laughter.

“Yeah, hot chips,” echoes Skye.

“Well, he’s a boy,” murmurs Abby.

I ask Rebecca if her parents are Christians and she says no. “I think my mum believes in God, she just doesn’t really feel the need to have him in her life. My dad is a scientist and he believes in evolution.”

Don’t some Christians believe in evolution?

“Yeah, my mum believes in evolution but she thinks that probably God’s behind it, or something.”

What differences did you and your brother find between the Baptist Church you went to and Hillsong?

“Baptists bring everything back to the Bible. Hillsong brings absolutely everything back to the Bible but I think they put it much more like, you can have it now. Like these old things can still relate to now time. Everything from the Bible they relate back to today.”

Don’t the Baptists teach this as well?

“Yeah, they do, but they don’t necessarily relate it so much back to real life.”

It seems a bit more like something in a book?

“Yeah. I think a lot of Catholic and other Christians are very caught up with the rules of Christianity and stuff, which is what most people see, but it’s not really about that. Like Abby said, it’s not really about religion, it’s about having a relationship with Jesus.”

On 13 January 2006, the Sydney Morning Herald blogger Andrew West wrote a piece on young evangelical Christians that produced a big rush from young correspondents, many of whom made the same point. “Please do not confuse God with religion,” wrote one. “Religion is an instrument of humanity, not of God.” This sounds like a restatement of the fundamental principle of the Protestant Reformation, namely that no one or no thing should come between the individual soul and its God.

If only it were that simple.

“But there must be some rules in your group,” I say.

“There’s not so much rules,” Rebecca replies, “there’s guidelines, stuff like the Ten Commandments and you shouldn’t swear and you shouldn’t take drugs, don’t have sex before you get married. I think if you look at every single rule in the Bible, they’re all there to protect you from things that in the end are going to hurt you. Like even if having sex before marriage mightn’t hurt you, you get attached and you’re gonna get your heart broken … But if you break the rules, it doesn’t mean that you’re not a Christian.”

So if you do break the rules, what’s the reaction from the group?

“Well, you don’t get expelled or anything. It’s just, like, if you want to tell someone about it they’ll just talk to you and there are leaders or older mentors who are there for talking about stuff.”

Abby intervenes to tell me about youth “cells”. These are teenage support groups that meet weekly at the home of either of the cell’s two mentor figures (young women in their early twenties). These meetings are clearly something the girls enjoy and look forward to, although they joke about how they have to stop speaking of “cell” groups because of the association with terrorism.

“Yeah,” says Skye, “like we’re terrorists for Jesus.” They giggle.

I have tried so far to be neutral but at this point cannot resist a skewed question. “Is God masculine?” I ask (this is an all-girl enclave, after all).

Abby tells me about a girl they know called Ella who wrote a paper on that subject for her HSC, a paper in which she argued that God is not gendered. “It was really interesting,” says Abby.

What did it say?

The girls are vague about the argument (it was some time ago) but indicate they are receptive to the idea.

So why do we say “he”?

Abby: “It’s just tradition, I suppose. Like if you say ‘she’ you’re kind of making a big thing of it when it’s not really that …” She searches for the word, “… relevant. There’s quite a lot of women preachers at Hillsong, which is nice because they can relate to you as a girl. But I don’t think about that much, probably because, with the women’s rights thing, like, now we’ve got them all.”

I let that pass. They’re too young to know, to have tested out, which of the “women’s rights” they’ve really “got” and which are only apparent. Right now I’m more interested in that fraught question of “rules”, and with it, sin and damnation. On this matter the girls are concerned to make it clear that there is a degree of tolerance in their youth group. Rebecca and Abby believe strongly in no sex before marriage, but some couples in their group are having sex and they are not “shunned” for it. Abby tells me that at summer camp they were given a sex talk by a woman preacher, who explained how she had had sexual partners before marriage and now regretted it. As the preacher explained it, it’s like a process of negative imprinting, where each time you have sex you leave behind a little piece of yourself “like the print coming off a piece of paper until the print is all worn away”.

Rebecca chimes in: “It’s like, every time you have sex with someone, you give away a little bit of yourself to that person. So you should make sure it’s the right person, because if you just throw it away then you’re definitely going to regret it.” Later in the conversation we loop back to this and the imprinting metaphor appears in another, reverse version. This time it’s bits of other people you have sex with that stick to you, and you end up carrying a lot of “baggage”. “And you get to be a piece of paper that’s like, either hollow or it’s got all this baggage, all these bits, colours, stuff sticking to it. There are people our age who are having sex and I guarantee you most of them will regret it – like, how I lost my virginity in an elevator.”

Skye grimaces. “Yeah. Charming.”

I see in this a kind of strategic sense for young girls, a need to find a safe zone to be in while they wait until they are ready. My generation rebelled against the puritan hypocrisy of its elders and fought for sexual freedom, especially for women, but “freedom” can become as despotic as puritan repression. I think of that old warhorse Norman Mailer, who declared recently that it would be “nice” if we could abolish the ’60s sexual revolution, and its excesses, and “go back and start again”. I think of the sixteen-year-old I know who lives in an outback town in Queensland who confided in me recently that she was being taunted and mocked in her peer group for still being a virgin. “I just haven’t met anyone yet that I want to have sex with,” she said, deeply resentful of the pressures towards sexual conformity. And perhaps some girls have a sense of having been devalued by the sexually exploitative images of women that are everywhere in the culture and continue to be demeaning. In a Christian youth group they find a sense of the consecration of their bodies as having singular worth. But this is not the old puritanism and should not be mistaken for it. On the other hand, have any of them yet experienced real sexual awakening? Will they feel the same way when they are twenty-five, or even twenty-one?

So what about these rules? There’s no sex before marriage, and what else?

Abby: “Everyone has different ideas. Like Skye believes in abortion and Rebecca doesn’t. Everyone has their different beliefs.”

I’m glad they raised it and not me. So it’s alright to disagree about certain things, like abortion?

“Yeah.”

I ask Skye for her views on this most fraught of subjects for Christians and she is lucid, having clearly had reason to rehearse her argument. “We don’t know for certain when the baby’s soul enters the mother’s body,” she shrugs. “There’s nothing in the Bible about that. If Jesus appeared to us today and said that it definitely is there from the first moment, then I might be against abortion. But it could be that until the baby is born it’s part of the mother so the mother should have the say up until then.” Rebecca: “My brother says it’s murder.”

Abby: “I think you have to look at the outcome. Like if you ban abortion, the woman might go and get one anyway under unhygienic conditions and die.”

So for you, being in favour of abortion is a lesser of two evils thing?

Abby: “Well, I’m not in favour of it as a general thing but I think it should stay legal.”

So these then are my three types, the hardliner (Rebecca), the freethinker (Skye) and the moderate (Abby). Does this mean that “sin” for them is a slippery concept? How much leeway do they have with the rules before they are damned in eternal fire and brimstone?

What does being “saved” mean to you?

Rebecca is in her element here. Despite Ella’s speculative HSC paper she is the group’s unhesitating dogmatist. “You get saved basically by just accepting Jesus, by acknowledging that you have sin in your life, you’re not perfect and acknowledging that Jesus is the way to make that right, and you say: ‘Jesus, I want you into my life.’ And once you’ve got Jesus in your life, basically you’re saved.”

What about if you die and you’ve done some bad things – do you still go to heaven?

“Yeah, as long as you’ve accepted Jesus into your life.”

Here we have the Protestant doctrine of justification by faith alone, as clearly and unambiguously stated as it could be.

What about if you’re a good person and lead a good life but don’t believe in Jesus? Or if you’re a Muslim or Hindu and have a love for God and you also think Jesus was a great prophet. You don’t think these people could go to heaven?

Rebecca: “Jesus was above all else. You have to understand that and that’s what makes you a Christian.”

So the other people are sincere but basically they’re out of luck, because they love God but in the wrong form, or the wrong God.

“They love God, but they don’t understand what Jesus was. They don’t understand that he died for our sins so that we didn’t have to go to hell. If you just believe that Jesus was a regular prophet, then you can’t understand that he died for our sins. But in the end it’s really not about what you know and what you don’t know, it’s do you have a relationship with Jesus. Basically it doesn’t matter what you call yourself, or what you’ve done, if you have a relationship with Jesus, that’s it, pretty much.”

And everyone else goes to hell?

“Yeah, much as it sucks, you have to understand that Jesus was the only saviour.”

“Much as it sucks …” This is a phrase that, in the present context, has a certain charm because Rebecca is deploying it as a form of tact; the rueful colloquialism is a concession to me, to soften the message. She does not want to be rude, to suggest the brutal despatch with which I might one day be consigned to hell. At the same time, her honesty and characteristic forthrightness cannot fudge the essential message.

Abby sees it differently. “I don’t think people who aren’t Christian are going to go to hell,” she says, “and I think it’s really immature to mock other religions. Like we had this guy come in to religious education at school once and he was making fun of Buddhists and other people and I think that’s immature.”

Do you get into arguments about this?

“It’s hard to bring that up in front of other people because that’s what they strongly believe, so I feel it’s my personal belief and I don’t need to discuss it with anyone. I just keep it to myself, except with Rebecca and stuff … Some people who come to [Hillsong] Youth haven’t thought about things much before, so they tend to take on the whole package without thinking it out for themselves.”

It’s on the tip of my tongue to ask Abby what she means by “immature”, but I decide not to press it. She has been brave in speaking out at youth group and stating her convictions, but she is not of an argumentative caste of mind. And despite her differing with Rebecca on this fundamental point, their friendship remains intimate and unwavering. Such are the mysteries of human relationship, even at this age.

There are many more questions I would like to ask, but time is running out and I opt to make my last question somewhat political: Are you asked to give money at Youth meetings?

Abby: “Yeah. I’m not sure I should be commenting on this because it’s just my personal opinion but like, with giving money, you don’t have to give a big amount. If you give a dollar, it’s something that means something to you, to help build up the church.”

Are there any guilt trips laid on you if you don’t give?

“They do bring up the point that you could go and spend that money on McDonalds after, or you could give it to something that’s helping young people.”

So there is a bit of a guilt trip?

“Yeah, but I don’t really feel guilty.”

This provokes another outburst of laughter from the girls, and at that point Abby’s father comes into the room and signals that time is up and he is ready to drive them to a cell meeting. They stand, and Rebecca adjusts her ha...