![]()

CHAPTER 1

IN THE FAMILY PAPERS

WHEN I WAS A CHILD we spent many holidays at my mother’s family home, a grand but decaying old house in the Girvan valley of Ayrshire, south-west Scotland. Her family, the Fergussons, had lived in the valley for more than 500 years: the house, Kilkerran, was a living museum of the preceding generations and of their adventures. The Fergussons had roamed far, ‘serving the Empire’: soldiers and politicians stared down from their portraits at us, their books were on the library shelves. The rooms where we played – there were more empty and disused than actually lived in – were full of their trophies: medals, uniforms, swords (ceremonial and real), stuffed animals, strange hats all jumbled up with the toys of long-ago childhoods. We were steeped in the family history; we learnt to revere it and those serious-faced ancestors. They did not seem very distant: the adults talked of them and their feats and faults as though they had just departed.

The attic floor was servants’ rooms, from the days when the house had a dozen or more of them. In the early 1940s it housed evacuees from the German bombing of Glasgow and Clydeside. Now it was abandoned, a continual battle being waged against the dry rot that threatened the roof. Heaps of junk and broken furniture were piled inside the damp rooms. One rainy day we discovered two half-length coats of chain mail in a former maid’s room. We tried to put them on. They were incredibly heavy – it was impossible to pull them over your head. The only way was to crawl into the tunnel of rusty links and then try to stand up.

My grandfather laughed when we told him we’d found suits of armour from the Crusades. He was a gentle and kind person, a historian and journalist – not very like his soldiering forebears. We did not see him much; during the week he was in Edinburgh, where he ran Scotland’s national records office. At home he was often shut away in his cigarette smoke-filled study ‘working on the family papers’. These were a vast trove. The most important, dating from the seventeenth century, were kept in a thick-walled room at the house’s ancient heart. Being shown round the strong-room by my grandfather – who told a good ghost story – was a holiday treat.

No, he told us, it was not armour but chain mail, and not from the Crusades but much more recent – 1839, sixty-five years before he was born. The suits had been made for the Eglinton Tournament. It was a huge fancy-dress party, he said, where families from around Ayrshire, and from all over Britain, came together to pretend to be medieval knights and joust at each other on horseback as in the olden days.

‘With real spears?’ we asked.

‘Oh yes,’ he said, ‘it was dangerous. And very expensive. Sadly it was not a success: it rained for the whole weekend.’

Years later I found an old paperback book about the tournament titled The Knight and the Umbrella, by Ian Anstruther. Quotes from my grandfather’s enthusiastic review for The Bookman magazine fill the back cover. Anstruther tells how, at the dawn of the industrial age, a group of wealthy aristocrats met at Eglinton Castle in Ayrshire to re-stage a spectacle of the height of feudal times. The novels of Sir Walter Scott, full of chivalry and romance, were an inspiration.

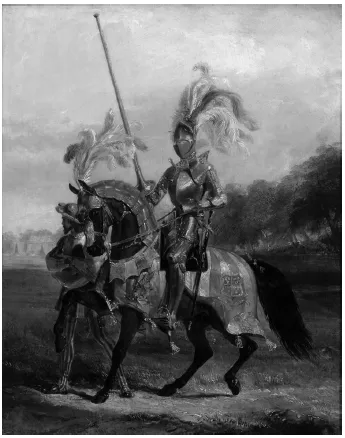

The tournament was the idea of Archibald Montgomerie, 13th Earl of Eglinton, a spoilt twenty-seven-year-old aesthete from an ancient Ayrshire family. He had been infuriated at the lack of traditional ceremony at the coronation of Queen Victoria the previous year. He resolved to put all that right, to remind a swiftly modernising Britain of the greatness of its past and the splendour of its nobility. This fancy was to cost him £40,000, perhaps the equivalent of £3.5 million today.1

The knights, some of the best-known playboys of the era, bought horses, trained them and practised jousting with lances. They spent fortunes on outfits for themselves, their horses and their wives. Meanwhile a great medieval fairground, with grandstands, encampments for the knights and their retainers, pavilions, marquees, lists and tiltyards, was set up outside Eglinton’s brand new Gothic castle. Rehearsals were held and all was set for a weekend in August 1839. The new-fangled railways laid on special trains and a crowd of more than 100,000 turned up. To get a ticket for the grandstand you had to promise you were a supporter of the Conservative Party. Queen Victoria expressed regret that she could not attend.

Lord Eglinton, ‘Lord of the Tournament’, wearing armour that was gold-plated, or gold-painted, was escorted by a troop of halberdiers. Prince Louis Napoleon (later Emperor Napoleon III) and the Duchess of Somerset (‘The Queen of Beauty’) dressed up to join the opening procession. Prince Louis’s presence was particularly pleasing to Archie Eglinton. As he liked to point out, his ancestor Gabriel Montgomerie had managed to kill King Henri II of France – by mistake – in a joust at a tournament in 1559. Montgomerie, who was captain of King Henri’s Scots Guards, skewered him through the eye when a splinter from his lance entered the king’s helmet.

Archibald, 13th Earl of Eglinton, dressed as the Lord of the Tournament, Henry Corbould c. 1840.

Nineteen knights made themselves ready, each of them attended by esquires, pages and men-at-arms. My grandfather’s great-uncle, John Fergusson, acted as esquire to ‘The Knight of the Ram’, who, under the armour, was the Hon. Captain Henry Gage. It was nineteen-year-old John’s chain mail hauberk into which we had been trying to clamber.

Interest was intense: the newspapers covered the preparations, reported the worries of the police over crowds and the possibility someone might be killed, and then mocked mercilessly when it all went wrong, in the most traditionally Scottish way. ‘The lists in the park of Eglinton Castle at this time exhibit the appearance of a pond,’ reported The Times as the tournament weekend began. The visitors had to wade through mud for a mile or more to get to the site.

A gale of bitterly cold rain drenched the vast crowd, flooding the royal box and the grandstand and knocking down the banqueting tent. The spectacle of men on horses charging at each other turned out to be quite dull, so much did the mud slow the action down. There was just one injury to the knights: Lord Stafford’s son, Edward Jerningham, sprained his wrist. The whole event was a disaster. The Spectator magazine titled its report ‘Eglintoun Emasculated Mopstick Middle Age Recovery Society’.2 Queen Victoria pronounced the tournament ‘the greatest absurdity’.3 The age of chivalry had had its last blast.

The Knight and the Umbrella, published in 1963, sets the story well in the time; it laughs kindly at Eglinton and his friends’ quixotic crusade against the dullness of modern, democratising Britain. Ian Anstruther, the author, reprints the invoices from the one man who did well out of the tournament, Britain’s last remaining armourer, Samuel Pratt. Just the hire of a suit of armour from him cost £60– £5,300 today.4

Anstruther never questions the source of all the money spent on the three-day wash-out. The answer to that was in part in the papers on which my grandfather worked. Our family, and most of the neighbours, cousins and friends who took part in the tournament – Lords Glenlyon, Cassilis and Airlie, the families of Hamilton, Dallas, Fairlie, 5 Johnstone, Crawford, Montgomerie, Montgomery, Kennedy, Oswald, Cunningham, Balfour, Dundas, Campbell, Balcarres Lindsay, Hunter Blair, Wemyss – had made or added to their fortunes quite recently through an industry that was not at all romantic or honourable.

The same was true for the families of many of the English knights and esquires – Kents, Gages, de la Poer Beresfords, Howard de Waldens, Staffords and Seymours – who performed that day. The 250-year-old enterprise that was the source of some of their money, plantation slavery in the British Caribbean, had finally ended just a year before the tournament’s opening day.

Some of the families, like the Fergussons, Hamiltons and Hunter Blairs, still had slave plantations when the Act abolishing slavery was passed in 1833. They had got a windfall as a result. The British government had brought about the end of slavery in the Caribbean colonies by the simple expedient of buying off the 46,000 slave-owners: paying them a sum per person owned by way of compensation ‘for loss of property’. The enslaved people received nothing,

The Hunter Blairs and the Fergussons, who jointly owned 198 enslaved people on their Jamaica plantation, received a compensation payout in 1836 of £3,591, eight shillings and eightpence: a little over £3 million today.6 The total cost to the British taxpayer was £20 million, perhaps £17 billion today, though some analyses put it much higher.7

In the Caribbean, even now, people who are the descendants of the enslaved Africans the British imported ask what was actually done with the profits their ancestors laboured and died to make? Did any good things come about? The Eglinton Tournament, gilt armour, velvet caparisons, trained horses and twelve-foot lances designed to shatter in a way that would not injure the jousters, is a part of the answer.

* * *

In the old servants’ hall

The history is kept down in the guts of the house. Only three of the five floors of Kilkerran are lived in now, the basement and the huge attics essentially abandoned. In the old servants’ dining hall tiers of shelves rise from dust and pigeon droppings. On them are boxes, ledgers and files containing the paperwork of four centuries of the family’s business affairs, political machinations, imperial appointments and military exploits.

There are diaries of campaigning aunts and grandmothers (suffragism and Zionism), of grandfathers and great-uncles who were subalterns and generals during the imperial wars in Crimea, Sudan, South Africa, Flanders and Burma. There are photo albums, common-place books, letters from children at boarding school and notes from prime ministers. There are a lot of bills too.

My grandfather was the last man with deep knowledge of what the shelves contained. He died in 1973. He was Sir James Fergusson, an eminent journalist and historian who was for twenty years in charge, as Keeper of the Records, of all Scotland’s historical archive. His own family’s archive was his chief hobby, and the source of several of his published books.

In the family, the achievements and adventures of the forebears were much discussed. The Carribean history was not. ‘It never came up when we were young,’ my mother says now. Much later, when planning to visit Jamaica and the Rozelle plantation, my grandfather discussed the slave-owning past. He told his children that though, like many families in Scotland we had owned people as slaves, it was only briefly and we had made no money. My generation knew nothing about it at all.

My grandfather was a good and kind man and a meticulous, old-fashioned scholar. There was deep shame in the papers, and it called to question the origins of the family’s narrative of itself as philanthropic, disinterested servants of Britain and the Empire, champions of liberal causes. I think my grandfather believed that full knowledge of this past was not a burden his heirs should carry. The story was close to him: his grandfather had sold the Jamaica plantation and died while on a visit to the island, a victim of the earthquake of 1907. As eighth baronet of Kilkerran, my grandfather and others in the family still carried the names of the eighteenth-century ancestors – James, Alexander, George, Adam and Charles.

* * *

The papers don’t give up their secrets easily. Heavy foolscap sheets of deeds and contracts unfold with a creak, resisting any attempt to scan them. The lighter paper used for letters and notes may crack into fragments that will blow away on a breath. Water blurs a sentence just as it seems about to give up some meaning – tropical or sea damp, or spray from the hoses of the firefighters who saved the papers and the house from a fire some decades ago. The outside of some bundles is black from the smoke of that misfortune.

The cursive italic is often crammed on the page, as though paper was a hideous expense. But that cannot have been the problem, because the sentences go on and on and round in circles. Full stops are rare things. And while my ancestors and their correspondents turn their phrases with elegant, ecclesiastical rhythms they are averse to saying anything briefly. Squeezing meaning from the script can be eye-aching, brain-numbing work.

Some of the documents are more plain. A few tell you things with all the clarity of a punch in the stomach. None more so than the plantation accounts books, with their cold lists of the ‘increase’ and ‘decrease’ in human beings. More detail comes in the inventories periodically made of all the sellable assets on the plantations. The first of these I saw was in a bundle that my ancestral uncle Sir Adam Fergusson filed away in January 1781, with this covering note:

The Within Letters are my only Apology for engaging in that unfortunate business of Tobago. Those who do not know what it is to be anxious to procure an establishment for a beloved Brother will think them none. Those who do, though they may not think them a sufficient Excuse for the Folly, will perhaps allow that they extenuate it.

Inside, among the letters, is a formal document titled ‘Inventory and appraisement of Carrick Plantation in the Parish of St John, the property of Sir Adam Fergusson Baronet’ and dated 8 November 1777. Eleven foolscap pages follow, bound with thread and laid out as an accounts book. It has been drawn up by a professional and signed by other Tobago landowners, all Scots. It lists everything of any value, from the rooms of the house Sir Adam’s brother James had built in Tobago down to the carpentry tools, James’s clothing, cutlery and the teapot. But the most valuable things are listed on the first page, starting with the land and its crop. Next comes ‘Buildings’ and then ‘Slaves’.

That section begins with the title ‘House’ and five names: Emoinda, Rachael, Monimia, Sophia and Peggy. The last three have their roles stated: washerwoman, cook and sick nurse. Emoinda and Rachael were maids, perhaps. In the next column these humans’ value is estimated: Emoinda at £65, Rachael at £57 and Peggy, the nurse, £90.

Peggy is nearly the most valuable person on the plantation – valued higher than Scotland, the carpenter (£80) or Solomon, one of the watchmen (£81). Quashie, listed as one of the two ‘drivers’ – field team leaders, or bosses – is priced at £108. The inventory lists a total of 79 people, most of them under the heading ‘Field’. Their total value is £4,198 – nearly £7 million today....