![]()

PART 1

Hebrews 1:1–4:13

Hearing God’s Word with Faithful Endurance

With the inclusio that binds together the first major section of Hebrews, the author focuses the attention on God’s word. “God . . . has spoken in a Son” (1:2); God’s word is “living and active, sharper than any two edged sword” (4:12). To say that God has spoken through a Son who is above the cosmos (1:3–4) is to recognize that this message is no ordinary word. It is the offer of a “great salvation” (2:2–3) and the promise (4:1) that the people of God will reach the ultimate place of rest (4:9). The author maintains the theme of God’s speech throughout the homily, finally reminding the community of the blood “that speaks better than the blood of Abel” (12:24).

As the author begins this “word of exhortation” (13:22), the audience has not yet reached the promised land. Like their predecessors in ancient Israel they wander through the wilderness, and the promise appears more distant than ever. Consequently, their destiny rests on their willingness to “pay attention” (2:1), recognizing that they have reached the urgent moment when God speaks to them, “Today, if you hear his voice, do not harden your hearts” (3:7–8a). As ancient Israel learned, God’s promise of salvation is also the oath that declares, “They shall never enter my rest” (3:11), to those who refuse to listen. Thus God’s word is both the promise of salvation and the two-edged sword of judgment (März 1991, 263). Because “God has spoken to us in a Son” (1:2), “we must give an account” (literally “to whom is our word,” 4:13). Only those who listen and demonstrate faithful endurance through the unpleasant conditions of the wilderness will enter the promised land.

Part 1 of Hebrews sets the stage for the rest of the homily. The author maintains the wilderness setting, describing his listeners as the people on the move toward the promised land. He introduces the theme of Jesus as the pioneer (2:10) who leads the way and consistently invites readers to follow where Jesus has gone (4:14–16; 10:19–23; 12:1–2). He insists that readers endure faithfully, even when they have not received the promises (3:1–4:13; 10:32–12:13). Thus the urgent situation demands that the people hear the voice of the God who has spoken.

► Hearing God’s word with faithful endurance (1:1–4:13)

Exordium: Encountering God’s ultimate word (1:1–4)

Narratio: Hearing God’s word with faithful endurance (1:5–4:13)

Paying attention to God’s word (1:5–2:4)

The community’s present suffering (2:5–18)

Hearing God’s voice today (3:1–4:13)

Probatio: Discovering certainty and confidence in the word for the mature (4:14–10:31)

Peroratio: On not refusing the one who is speaking (10:32–13:25)

![]()

Hebrews 1:1–4

Encountering God’s Ultimate Word

Introductory Matters

Hebrews begins with an elegant style that is without parallel in the NT. Although it has an epistolary ending (cf. 13:18–25), it begins not with the traditional epistolary form but with a carefully structured combination of clauses in 1:1–4 (one sentence in Greek) that ancient writers called a period (periodos), literally a “way around” (peri + hodos), that organizes several clauses into a well-rounded unity. This elegant style, which is rare in the NT but common in Hebrews (cf. 2:2–4; 4:12–13; 7:1–3, 26–28; 12:18–24), reflects the author’s gift for language. The literary quality of the book is evident also in the use of alliteration, with five words in verse 1 beginning with the letter p (polymerōs kai polytropōs palai . . . patrasin . . . prophētais). Alliteration, especially using the letter p, was also a common device at the beginning of a speech or literary work (cf. Homer, Od. 1.1–4, polytropon . . . polla . . . pollōn; Luke 1:1, polloi . . . peri . . . peplērophorēmenōn . . . pragmatōn).

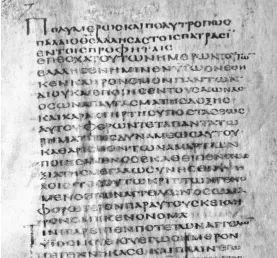

Figure 1. The Opening of Hebrews in an Ancient Manuscript.

Codex Alexandrinus is a fifth-century manuscript of the Greek Bible. The photograph shows the beginning of Hebrews at the top of the second column of folio 139 recto.

Like ancient orators, the author has artfully developed the opening words of his sermon, knowing that the beginning of the speech, known as the exordium, is the most critical part of the message (cf. Berger 1977, 19). Hebrews 1:1–4 conforms to the classical understanding of the exordium, establishing the expectations of the readers and preparing the way for the message that follows. The author crafts an artful periodic sentence in place of the customary epistolary introduction in order to prepare the audience for the distinctive form of address that will follow. The opening words in 1:1–2a introduce the theme of God’s speech, which the author later develops (cf. 4:12–13; 5:11; 12:24–25). The “purification for sins” in 1:3c anticipates the theme that the author develops in 9:1–10:18 (cf. 9:14, 22, 23; 10:2), indicating that the Levitical sacrifices provide the lens for the interpretation of the death of Christ. According to Exod 30:10, the Day of Atonement effected purification: “Aaron shall make atonement once a year upon its horns (of the altar); from the blood of the purification for sins of atonement he shall purify it once a year.” According to Lev 16:30, the sacrifice of the Day of Atonement purifies the people from sins.

The claim that the Son has been exalted to God’s right hand is a pervasive theme in Hebrews (cf. 1:13; 8:1; 10:12). The declaration that God has spoken in the past and “in these last days” anticipates the homily’s consistent references to God’s speech in the past and in the present (cf. 2:1–4; 4:12–13; 12:25–29). The note of continuity and discontinuity between God’s speech to the fathers and in a Son (1:1–2a) anticipates the comparison between the institutions of the old and the new covenant throughout the homily. Thus the author follows common rhetorical practice by providing a table of contents in the opening words of the homily.

The rhythmic praise of the Son has suggested to numerous scholars that 1:1–4 contains a hymn, in whole or in part. Indeed, comparison with other NT passages that are widely recognized as hymns reveals numerous parallels with 1:1–4. Like Heb 1:1–4, NT hymns have a christological focus, commonly describing the Son’s role in creating and sustaining the universe (cf. Col 1:16–17), descent to earth, ascent to heaven, and adoration by heavenly beings (cf. Phil 2:6–11; 1 Tim 3:16; also 1 Pet 3:22). The titles describing the Son’s eternal nature (i.e., “radiance of his glory,” “exact representation of his being”) resemble early Christian hymns, which describe Christ as the “form” (Phil 2:6) or “image” (Col 1:15) of God. The fact that these titles are used nowhere else in Hebrews has also suggested that the author is citing the words of a hymn. In addition, the parallelism and the relative clauses introduced by “who(m)” are also common features of NT hymns that are found in Hebrews. Consequently, Günther Bornkamm (1963, 198) has suggested that the prologue of Hebrews is a hymn. His view is widely accepted among scholars (e.g., Deichgräber 1967, 367; Hengel 1983, 84; Hofius 1991, 80).

These elements are not, however, sufficient evidence that the author is quoting a hymn. Indeed, most of the writers who identify the prologue of Hebrews as a hymn have difficulty demarcating the hymnic material from the surrounding prose. The introduction of major themes in 1:1–2a and 1:3b–4 indicates that the exordium is deeply rooted in the author’s own message. The author’s use of the periodic sentence at critical transition points throughout the homily suggests that he is not quoting a hymn (cf. 2:1–4; 4:12–13; 7:26–28). Indeed, the correspondence between the periodic sentence here and the one in 12:18–24 suggests that he has crafted this introduction to move the audience toward his goal.

Only in the present participial phrases “[being] the radiance of his glory and exact representation of his being” and “bearing all things with his powerful word” (1:3a–b) is the language noticeably different from the author’s description of the Son and reminiscent of NT hymns. Although these descriptions are parallel in content to the NT hymns, the author’s terminology has no parallel in the NT, which nowhere else describes the Son as the “radiance of God’s glory” or the “exact representation of his being.” The author of Hebrews could have appropriated these terms from wisdom literature and Philo, where they are widely used.

Whereas 1:1–2a and 1:3b–4 summarize God’s revelation of the Son within history (“in these last days,” “having made purification for sins”), 1:2b–3a describes the Son’s relationship to the cosmos in a series of relative clauses, all in the present tense, that echo Hellenistic reflection about Wisdom and the logos as mediators between God and the world. “All things” is a common designation for the totality of the universe (cf. John 1:3; Rom 11:36; 1 Cor 8:6; Heb 2:10) in Hellenistic philosophy that was adopted in the literature of Hellenistic Judaism (cf. Philo, Spec. Laws 1.208; Heir 36). God made his firstborn Son (cf. 1:6) “heir” of all things, fulfilling the promise to David that he would receive the nations as an “inheritance” (Ps 2:8; Koester 2001, 178). “Through whom he made the worlds” echoes NT affirmations about the Son’s role in creation (cf. John 1:1–3; 1 Cor 8:6) and is reminiscent of the claims in Hellenistic Judaism of the role of Wisdom and logos in the creation of the world (cf. Prov 8:22; Wis 7:22). “Worlds” (aiōnes), which is parallel to “all things,” can be used either temporally to mean “ages” (cf. 1:8; 6:5, 20) or spatially to mean “worlds” (cf. 11:3). The parallel to “all things” suggests that the author is speaking in spatial terms to describe the cosmos, probably including both the heavenly and the earthly world that will be the subject of the later discussion in the homily. In subsequent comments about the creation, the author does not mention the Son’s role, but describes God as the one who created all things (2:10) by his word (11:3).

In 1:3a–b, the author employs the present tense to describe the Son’s relationship to God and to the creation in language that Hellenistic Jewish writers, especially Philo of Alexandria, employed to describe Wisdom (sophia) and the word (logos). The “reflection of his glory and exact representation of his being” are parallel phrases that employ separate metaphors to describe the relation of the Son to God. “Reflection” (apaugasma) and “exact representation” (charaktēr) are parallel, just as “glory” (doxa) is parallel to “being” (hypostasis). “Glory” suggests the image of a shining light reminiscent of OT theophanies where the glory of God appeared (Weiss 1991, 145; Spicq 1994, 1:366; cf. Exod 16:10; 24:16; 33:18; 40:34–35; Lev 9:6, 23; Num 14:10; 16:19; 17:7 LXX [16:42 NRSV]; 20:6); thus it denotes the reality of God. Apaugasma, which c...