![]()

![]()

1

INJUSTICE OR GOD’S WILL?

Early Christian Explanations of Poverty

STEVEN J. FRIESEN

Brazilian theologian, churchman, and activist Dom Hélder Câmara was known as an advocate for the poorest of the poor, not only in the slums of Rio de Janeiro, Olinda, and Recife, but throughout the world. Reflecting on his ministry he observed, “When I give food to the poor, they call me a saint. When I ask why the poor have no food, they call me a communist.” While the accusation of being a communist may seem somewhat quaint in North America in the early twenty-first century, in Latin America in the late twentieth century the accusation was often fatal. Nevertheless, between his ordination to the Roman Catholic priesthood in 1931 and his death in 1999, Câmara persisted in spite of great opposition, and these experiences allowed him to explore the difference between offering charity and promoting economic equality.

With his life, Câmara raised the question of whether almsgiving is a sufficient Christian response to poverty. Does the Christian gospel also require an analysis of the forces that create and exploit poverty? This is not an easy question, and I cannot answer it in the next few pages. But we can begin by asking whether the writers of the early church posed such questions. Did they analyze the phenomenon of poverty? Did they ask why the poor had no food? And if so, what did they say about it? What did the earliest churches see as the sources of poverty? Did they think the misery came from divine action or human action? And in response to the existence of poverty, did they promote charity or economic equality?

These are not burning issues in patristic studies. One can find many studies that talk about early Christian attitudes toward wealth and poverty (and especially toward wealth), but I was not able to find a single study on early Christian analyses of the causes of poverty. So let us boldly forge ahead where wiser minds have chosen not to go.

I focus on the earliest period—the texts from the first and early second centuries of the Common Era. Most of the Christian texts from this period do not address these questions directly. As far as I can tell, the origins of poverty is not a topic for discussion in Hebrews, 1–2 Peter, 1–3 John, Jude, 1 Clement, the letters of Paul, the letters of Ignatius, the Acts of Paul, Justin Martyr, or Irenaeus. Scattered references are found in the Jesus traditions of the gospels, but these are quite complicated and they will have to wait for a different study.

That leaves four texts around which to organize my investigation: the Revelation of John; the Letter of James, which is more accurately called “the Letter of Jacob”; the Acts of the Apostles; and the Shepherd of Hermas. Together, these four proto-Christian texts provide us with four distinct ways of explaining the causes of poverty, and with four calls to action regarding one of the most intractable human problems. They do not demonstrate a linear evolution in the economic thinking and practices of the early assemblies, for the texts come from several communities over the course of several decades. Rather, the texts illustrate four models for study and for action that I hope will facilitate analysis without oversimplifying the issues. Before we examine the texts, however, we need a framework for understanding economic inequality in the early Roman Empire, where these texts were produced.

Economic Inequality in the Early Roman Empire

In their analysis of Roman imperial society, Peter Garnsey and Richard Saller employ the poignant phrase, “the Roman system of inequality.” With this phrase Garnsey and Saller call our attention to the fact that the Roman Empire maintained its domination of the Mediterranean world through judicial institutions, legislative systems, property ownership, control of labor, and brute force. Like all societies, the empire developed mechanisms for maintaining multifaceted inequality, and like all so-called civilized societies the empire promoted justifications that made the inequity seem normal, or at least inevitable.

As we turn our attention specifically to the economic facets of the Roman system of inequality, there are three fundamental ideas to keep in mind. First, as economic historians point out, the Roman imperial economy was preindustrial. The vast majority of people lived in rural areas or in small towns, with only about 10 to 15 percent of the population in big cities of ten thousand people or more. This means that most of the population worked in agriculture (80 to 90 percent) and that large-scale commercial or manufacturing activity was rare.

Second, there was no middle class in the Roman Empire. Because the economy was primarily agricultural, wealth was based on the ownership of land. Most land was controlled by a small number of wealthy, elite families. These families earned rent and produce from the subsistence farmers or slaves who actually worked the land. With their wealth and status, these families were able to control local and regional governance, which allowed them to profit also from taxation and from governmental policies. These same families also controlled public religion.

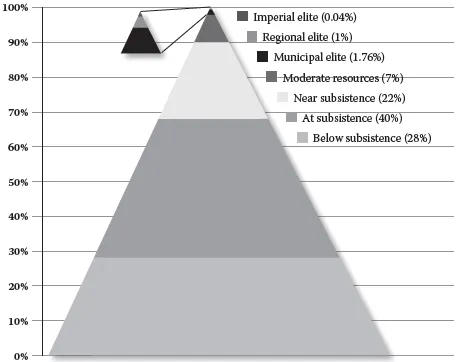

Third, poverty was widespread both in rural and urban areas. Interpreters of early Christian literature tend to underestimate the overwhelming poverty that characterized the Roman Empire. And when we do mention the problem of poverty, we tend to use the undefined binary categories of “rich” and “poor” in our descriptions. To promote clarity (and to force people to define their terms), I have developed a poverty scale that provides seven categories for describing economic resources (see table 1.1). The percentages are based on data from urban centers of ten thousand inhabitants or more, but we need to remember that in rural areas poverty was even worse: while superwealthy elites (categories 1–3) made up about 3 percent of an urban population, they were only about 1 percent of the total imperial population. The focus on urban centers is necessary because this type of city is where the audiences for these four texts lived. Another way to understand these figures is to render them as a pyramid chart that visually depicts the inequity involved (see figure 1.1). It is difficult to put monetary values on these categories because prices varied greatly in rural and urban areas; table 1.2 provides some rough guidelines.

Table 1.1. Poverty Scale for a Large City in the Roman Empire

| Percent of Population | Poverty Scale Categories |

|

|

| 0.04% | PS 1. Imperial elites: imperial dynasty, Roman senatorial families, a few retainers, local royalty, a few freedpersons. |

| 1% | PS 2. Regional or provincial elites: equestrian families, provincial officials, some retainers, some decurial families, some freedpersons, some retired military officers. |

| 1.76% | PS 3. Municipal elites: most decurial families, wealthy men and women who do not hold office, some freedpersons, some retainers, some veterans, some merchants. |

| 7% (estimated) | PS 4. Moderate surplus resources: some merchants, some traders, some freedpersons, some artisans (especially those who employ others), and military veterans. |

| 22% (estimated) | PS 5. Stable near subsistence level (with reasonable hope of remaining above the minimum level to sustain life): many merchants and traders, regular wage earners, artisans, large shop owners, freedpersons, some farm families. |

| 40% | PS 6. At subsistence level and often below minimum level to sustain life: small farm families, laborers (skilled and unskilled), artisans (especially those employed by others), wage earners, most merchants and traders, small shop/tavern owners. |

| 28% | PS 7. Below subsistence level: some farm families, unattached widows, orphans, beggars, disabled, unskilled day laborers, prisoners. |

|

|

Poverty is, of course, a more complicated phenomenon than the mere possession of financial resources. In the twenty-first century poverty is affected by many factors, and we should expect no fewer complications in ancient societies. In the early Roman Empire financial resources were probably the single most influential factor in determining one’s place in the social economy, but financial resources were not the only factor. Other factors would have included gender, ethnicity, family lineage (common or noble), legal status (slave, freed, or freeborn), occupation, and education. Patronage relationships were especially important in one’s economic survival, for a patron gave one access to restricted resources that were otherwise unavailable. In times of crisis a patron could mean the difference between life and death. But financial resources provide us with one way to open the discussions, and also have the virtue of sometimes being quantifiable in ways that other factors are not.

Table 1.2. Annual Income Needed by Family of Four

| Categories from the poverty scale are found in parentheses. |

|

|

| For wealth in Rome (PS 3) | 25,000–150,000 denarii |

| For modest prosperity in Rome (PS 4) | 5,000 denarii |

| For subsistence in Rome (PS 5–6) | 900–1,000 denarii |

| For subsistence in a city (PS 5–6) | 600–700 denarii |

| For subsistence in the country (PS 5–6) | 250–300 denarii |

|

|

Note: Adapted from Ekkehard W. Stegemann and Wolfgang Stegemann, The Jesus Movement: A Social History of Its First Century (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1999), 81–85. The estimates are based on 2,500 calories per day for an adult male, and include nonfood expenses such as housing, clothing, and taxes.

Figure 1.1. Poverty Scale Percentages

When we discuss the explanations of economic inequality found in early Christian texts, then, we must fight the tendency to impose the categories of modern industrial economies on the Roman Empire. Most of the recipients of these four texts lived in large urban areas with a preindustrial economy. Unless there is evidence to the contrary, we should assume that most or all of the recipients of a particular text lived near the level of subsistence.

Revelation of John: Apocalyptic Condemnation of Imperialism

The Revelation of John presents a blistering critique of Roman imperialism as the source of injustice and poverty. The text began to circulate in the late first century among urban churches in western Asia Minor (modern Turkey). The author described Roman imperialism as a system of blasphemous arrogance and deception: the powerful imperial elites (mostly PS 1) collaborate with members of the local aristocracies (PS 2–3) in order to deceive the masses into compliance.

Since the text is visionary with spectacular imagery, it makes its case not so much through argumentation as through symbols. The symbols are steeped in the traditions of Israel, but the author seldom quotes them. Instead, John narrates visions that mix elements of biblical traditions with allusions to the sociohistorical settings of the churches. The result is an apocalypse that portrays the Roman Empire as Satan’s tool, opposed to the God of Israel, and destined for destruction.

Two texts help us understand the critique better. The first text is the vision of two beasts in Rev. 13. The first half of the vision reveals a beast from the sea that clearly represents Roman imperialism; ...