eBook - ePub

First Corinthians (Catholic Commentary on Sacred Scripture)

- 310 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

First Corinthians (Catholic Commentary on Sacred Scripture)

About this book

Examine the New Testament from within the living tradition of the Catholic Church

In this addition to the Catholic Commentary on Sacred Scripture (CCSS), a seasoned scholar interprets First Corinthians for pastoral ministers and lay readers alike.

The CCSS relates Scripture to Christian life today, is faithfully Catholic, and is supplemented by features designed to help pastoral ministers, lay readers, and students better comprehend the Bible and use it more effectively.

Commentary features include:

● Biblical text from the New American Bible, Revised Edition (NABRE)

● References to the Catechism, the Lectionary, and related biblical texts

● Theological insights from Church fathers, saints, and popes

● Reflection and application sections for daily Christian living

● Suggested resources and an index of pastoral subjects

Attractively packaged and accessibly written, the CCSS aims to help readers understand their faith more deeply, nourish their spiritual life, and share the good news with others.

In this addition to the Catholic Commentary on Sacred Scripture (CCSS), a seasoned scholar interprets First Corinthians for pastoral ministers and lay readers alike.

The CCSS relates Scripture to Christian life today, is faithfully Catholic, and is supplemented by features designed to help pastoral ministers, lay readers, and students better comprehend the Bible and use it more effectively.

Commentary features include:

● Biblical text from the New American Bible, Revised Edition (NABRE)

● References to the Catechism, the Lectionary, and related biblical texts

● Theological insights from Church fathers, saints, and popes

● Reflection and application sections for daily Christian living

● Suggested resources and an index of pastoral subjects

Attractively packaged and accessibly written, the CCSS aims to help readers understand their faith more deeply, nourish their spiritual life, and share the good news with others.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Introduction to 1 Corinthians

Imagine that in a dream one night you find yourself in a parish where there are several drunks at Sunday Mass; where some members are claiming that there is no resurrection of the dead and that Jesus is not really present in the Eucharist; the parishioners are divided into cliques and factions; the president of the Altar Society is not talking to the head catechist; there is public unchallenged adultery and many marriages are in disarray; a group is dabbling in New Age spirituality; the liberals, the charismatics, and the traditionalists are all trumpeting their version of the church; and Masses are abbreviated for the sake of Sunday football—one of the many signs the parish has compromised heavily with the surrounding secular culture.

A nightmare? Not exactly. You were just experiencing a modern version of the community in Corinth. For this very reason, though, we have a lot to learn from these Corinthians, our enthusiastic but immature ancestors in the faith. The issues Paul faced with them are ones that, in one form or another, the church still struggles with today. Though Paul may not have thought so, we can be grateful that the Corinthians had so many problems because from the Apostle’s treatment of them, we can glean wisdom in dealing with ours.

The Author

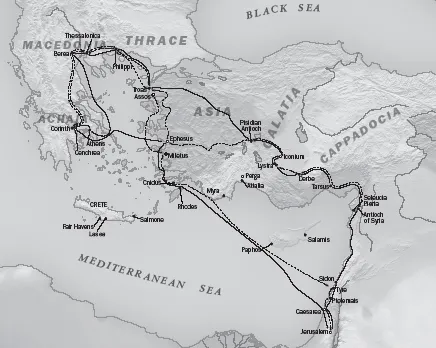

Readers who know of Paul’s life will recall his dramatic conversion from being a strict Pharisee and persecutor of the Christians in Palestine to being apostle of the Gentiles; his struggle to get the authorities in Jerusalem to accept the noncircumcision of Gentiles; his mission to Asia Minor and then to Macedonia and Achaia (today’s Greece); and his founding of churches at the price of beatings, imprisonment, and shipwreck. They know also of his martyrdom in Rome under Nero. This is the Paul who planted the Christian faith in Corinth around AD 50 and later wrote this letter from Ephesus, addressing his recent converts.

That Paul is the author of this letter has never been in debate. There is some doubt whether 1 Cor 14:33b–36, forbidding women to speak in the assembly, is from a later hand, since it appears to conflict with what Paul says elsewhere about the active role of women in the community’s worship (11:5, 13). If it is a later insertion, it was done quite early, since it appears in all the Greek manuscripts, though some have it at the end of the chapter. In any case, even with its difficulties, these verses were accepted into the canon of the inspired Scriptures, with their relevance to the Church today left to experts to propose and the Church to decide. Though called First Corinthians, this letter is not actually the first one Paul wrote, since he refers to an earlier letter in 5:9, which has been either lost or incorporated into what we know as 2 Corinthians.

Corinth: A Cauldron of Cultures

What kind of environment did Paul find when he first came to Corinth? Located at the end of a neck of land attaching the Peloponnese peninsula to mainland Greece and having a port facing east (Cenchreae) and another with access to the west (Lechaion), Corinth was geographically predestined to be a corridor of commerce and a potpourri of cultures (see map, p. 309).[1] Ships could be hauled across the isthmus on chariots on the four-mile paved railroadlike diolkos, whose grooves can still be seen on a surviving strip. This saved mariners sailing from Athens to the Adriatic 185 sea miles, and to Naples or Rome 95 sea miles.[2] It also spared them sailing around Cape Maleae, proverbially treacherous for seafaring. Ships with cargo too heavy for the diolkos would unload at one port and either haul the empty boat over the diolkos or load the cargo into a different boat at the other port. For various reasons, much cargo passed through Corinth itself. Being able to excise duty on the shipping, and celebrated for its shipbuilding and its production of bronze, ceramics, and textiles, Corinth was a wealthy city. It was also one of the ancient world’s largest. Its six-mile encircling wall locked into the Acrocorinth, a rocky hill rising to a height of 1,887 feet like an impregnable fortress.

Fig. 1. The Acrocorinth seen from the Temple of Octavia, a veiw Paul would have had in Corinth.

Corinth had a reputation of being one of the most sensual cities of the ancient world.[3] The temple of the Greek goddess Aphrodite stood atop the Acrocorinth, and prostitutes had their reserved seats in the theater. The term “Corinthian girl” meant prostitute, and korinthiazesthai (“to Corinthianize, live like a Corinthian”) meant to fornicate or promote the trade. If Aelius Aristides’ remark is true, “[Corinth] chains all men with pleasure and all men are equally inflamed by it . . . so that it is clearly the city of Aphrodite.”[4] Still, it was an expensive venture to go there, as reflected by the proverb “Not every man has the means to go to Corinth,” a saying known in Rome and applied by Strabo to the cost of fornication. The Isthmian games, held every two years, flourished nearby, and Paul may have arrived in time to witness them, or at least the crowds that flocked to the events. They would supply Paul with a wealth of athletic images, such as that of the imperishable crown awaiting Christians compared to the wreath of celery that the victors in the games received (1 Cor 9:25–27).

The culture of Corinth was such that it considered human lives—or at least certain human lives—expendable. Aside from abortion and the abandonment of babies (dropped off in a temple or left exposed), which was common in Roman times, of all the Greek cities in Paul’s day, Corinth was virtually alone in its enthusiastic adoption of the homicidal games of the Roman amphitheater. This may have been due to the Roman influence in its history. Originally a native Greek city, it was devastated by the Roman general Lucius Mummius in 146 BC, then was rebuilt in 44 BC by Julius Caesar, who established it as a colony of freed slaves. When Paul arrived between AD 49 and 51, he found a population of Romans, Greeks, and Near Easterners of every provenance, including a number of Jews—all attracted by the commercial advantages of the city. The city was composed of a small number of wealthy merchants, a large number of poor workmen, and a great number of slaves—an additional sign of the wealth of the city.

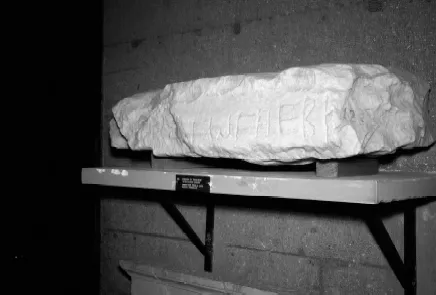

Fig. 2. This lintel, inscribed "Synagogue of the Hebrews," marked the entrance to the synagogue that was the successor of the one in which Paul preached in Corinth.

It was a city of gods and goddesses. Besides the Jewish synagogue, of which a later lintel has been discovered reading “Synagogue of the Hebrews,” there were temples to Apollo, Asclepius, Athena, Demeter, Dionysus, Kore, Palaimon, Zeus, Cybele, Isis, Serapis, Melkart, Sisyphus, and Aphrodite. The cults of Jupiter Capitolinus and of Artemis, the Great Mother, flourished, as did certain of the mystery religions, that of Isis surely, and probably that of Dionysus.

Such was the Corinth that Paul entered in the middle of the first century AD. Fresh from disappointment at the failure of his approach to the “wise” of Athens, who scoffed at Paul’s preaching of the resurrection (Acts 17:16–34), Paul began proclaiming that the wisdom and power of God were to be found in the cross (1 Cor 1:23–24).[5] Despite initial difficulties, leading to his break from the synagogue, his ministry of a year and a half there flourished, so that in 2 Cor 1:1 he could greet not only the Christians in Corinth but also “all the holy ones throughout Achaia.”[6] From here he wrote his First Letter to the Thessalonians and possibly the second.[7]

The Writing of 1 Corinthians

Paul certainly wrote this letter from Ephesus (1 Cor 16:8). According to Acts, at the end of his initial year-and-a-half ministry in Corinth, Paul sailed for Ephesus, where he stayed only a brief time before moving on to Caesarea, Jerusalem, and then via Antioch to his third missionary journey through Asia Minor (Acts 18:11, 22–23). When in the course of this third journey he arrived again at Ephesus, Apollos, an eloquent preacher from Alexandria who had ministered in Ephesus, had already been sent by that community to Corinth. There Apollos “gave great assistance” to the faithful (Acts 18:24–28), watering where Paul had planted (1 Cor 3:6). During this time, AD 53–54, two events prompted Paul to write our 1 Corinthians. First, a report arrived from “Chloe’s people” (1 Cor 1:11) that the community was splitting into factions, each claiming allegiance to one or another minister. The report, or others like it, told of a number of other disorders as well, such as one might expect from persons freshly converted out of paganism. Second, in a prior letter (see 5:9) Paul had warned the faithful, among other things, to avoid “fornication,” that is, falling back into pagan sexual practices. The community now responded with a series of doctrinal and moral questions in a letter carried to Paul most probably by Stephanas, Fortunatus, and Achaicus, leaders in the community (16:17).

Fig. 3. Paul's missionary journey to Corinth.

Structure and Literary Features

Although Paul treats many topics in this letter, he has organized his material in a very clear manner, which makes it easy to follow his thought. Aside from the address at the beginning and the lengthy conclusion in chapter 16, the letter falls into four major parts, as follows:

- Address (1:1–9)

- Disorders in the Community (1:10–6:20)

- Divisions over Personalities (1:10–4:21)

- Moral Disorders (5:1–6:20)

- Answers to the Corinthians’ Questions (7:1–11:1)

- Marriage and Virginity (7:1–40)

- Offerings to Idols (8:1–11:1)

- Problems in the Community’s Worship (11:2–14:40)

- Women’s Attire (11:2–16)

- The Lord’s Supper (11:17–34)

- Spiritual Gifts (12:1–14:40)

- The Resurrection (15:1–58)

- The Resurrection of Christ (15:1–11)

- Resurrection as Transformation (15:12–58)

- Conclusion (16:1–24)

Writing as Script

Paul follows the conventions of letter writing in his day. But it is unlikely that he himself wrote any of his letters. His letters to the churches were oral both at their origin in dictation and at the point of delivery by a public reading. In many cases, as in Paul’s discourse on the cross as power and wisdom (1 Cor 1:18–2:5), we can almost hear him preaching. And that is what he intends his listeners (not readers!) to hear as a single reader proclaims the message to the community to which the letter is addressed. It was ultimately not the written letter that represented Paul but the living voice of his representative. That is why even today Paul’s Letters are suited for proclamation at the liturgy. The written word is just a script for proclamation.

Our literate culture has not prepared us to be good listeners. Why should we bother to pay close attention to an oral proclamation if we can read it in our missalette or our Bible? If we forget what the reading was about, we can easily read it later. Not so for the people in Paul’s day. The only missalette they had was in their head. And that is where they recorded what they heard. Our literate culture has also taught us to lose our memories. A young technocrat next to me on a flight astounded me when he said: “I don’t have to remember anything. Anything I want to know or remember is right here.” He pointed to the latest cybertoy in his hand. This reliance on “where we can find it” outside ourselves makes moderns suspect that the words of Jesus in the Gospels were crafted by his followers much later, for who could remember all that he said? The suspicion is ill-founded. Our spiritual ancestors had recorders in their heads and could play them at will![8]

Why is this important for us who will be reading the text of Paul? Instead of zipping through the text (this applies especially to those of us who took speed-reading lessons), we need to re-create the sound either by reading it aloud or at least imagining someone proclaiming Paul’s preached letter to his addressees. And probably we need to make extra effort when listening to his word being proclaimed in the liturgy.

Literary Techniques

Whether we are listening or reading, it helps to be attentive to some of the literary techniques Paul uses. He uses wordplays, as when he plays on the difference between the “wisdom of word” (empty †rhetoric) and the “word of the cross,” and on human wisdom and power versus God’s foolishness and weakness, which is the true wisdom and power (1 Cor 1:17–25). Or the play on “all things are for me but not all things help me” (my rendering of the Greek wordplay in 6:12, which is not obvious in the NAB). Or between “using” and “using up” in 7:31. Or the double meaning of “followed them” in 10:4. Or the plays on the words “discerning” and “judging,” both forms of the Greek krinō, in 11:31–33.

Another technique Paul uses is the †diatribe, a common rhetorical device in the ancient world in which one argues with an imaginary opponent, as Paul does in 15:36–37 and elsewhere in his letters. You will also encounter lists of vices (5:10–11; 6:9–10) and virtues (13:1–13; see also 2 Cor 6:6–7; Eph 6:14–17; Col 3:12–14); in Paul sometimes one list immediately follows another (Gal 5:19–23). Paul also cites proverbs or wisdom sayings, either his own or ones borrowed from the biblical or Gentile culture of his day: “A little yeast leavens all the dough” (5:6; Gal 5:9). “Bad company corrupts good morals” (1 Cor 15:33). And he knows the power of metaphor: “You are God’s field, God’s building” (3:9). “Your body is a temple of the holy Spirit” (6:19).

Paul delights in asking his listeners rhetorical questions: “Do you not know that you are the temple of God, and that the Spirit of God dwells in you?” (3:16). “Do you not know that the holy ones will judge the world?” (6:2). “Do you not know that we will judge angels? Then why not everyday matters?” (6:3). “Can it be that there is not one among you wise enough to be able to settle a case between brothers?” (6:5). “Do you not know that the unjust will not inherit the kingdom of God?” (6:9). “Do you not know that your bodies are members of Christ? Shall I then take Christ’s members and make them the members of a prostitute?” (6:15; see also 6:16, 19; 7:16; 14:6–9, 16). The rhetorical question is both a compliment (the speaker presumes the hearer knows) and a challenge (but you seem to have forgotten).

Early in 1 Corinthians, Paul makes it clear that rhetoric for rhetoric’s sake is foolishness, but he does not hesitate to use rhetoric ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Pagse

- Endorsements

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Editors’ Preface

- Abbreviations

- Introduction to 1 Corinthians

- Cliques and the Cross (1 Cor 1)

- The Power and the Wisdom (1 Cor 2)

- Our True Boast Is in God, Not Ministers (1 Cor 3)

- Servants and Stewards (1 Cor 4)

- Cleansing the Community (1 Cor 5)

- The Court and the Courtesan (1 Cor 6)

- Marriage and Virginity (1 Cor 7)

- Idols: Freedom and Conscience (1 Cor 8)

- Paul’s Personal Example (1 Cor 9)

- Warnings and the Eucharist (1 Cor 10)

- Problems in the Community at Worship (1 Cor 11)

- Many Gifts, One Body (1 Cor 12)

- Love, the Heart of the Gifts (1 Cor 13)

- The Gifts in Practice (1 Cor 14)

- The Resurrection (1 Cor 15)

- Conclusion (1 Cor 16)

- Suggested Resources

- Glossary

- Index of Pastoral Topics

- Index of Sidebars

- Map

- Notes

- Back Cover

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access First Corinthians (Catholic Commentary on Sacred Scripture) by George T. Montague, Williamson, Peter S., Healy, Mary, Peter S. Williamson,Mary Healy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Biblical Commentary. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.